You got both your Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in lighting design. How did you land on this career path?

As a school graduate, I didn’t have a vision of myself as a lighting engineer. I just loved physics and math, so I wanted to apply to a program where I’d be using these subjects. My older sister helped me make my choice: she was graduating from university and could lend me her experience. Eventually, only the program in lighting engineering at Moscow Power Engineering Institute was left on our list, so that’s where I ended up going.

It might seem like an unexpected choice and quite a narrow field, but I haven’t once had regrets about it. This field gives you the chance to grow in very different areas connected to light, from plasma physics to architectural lighting. As a Master’s student, I ventured into interdisciplinary studies: with a Master’s student from a different faculty, we studied the effect lighting stimuli can have on electrical activity in different regions of the brain. We showed our participants different colors on a diode panel and then analyzed their brain activity using the EEG data we collected.

Did you find application for your skills after graduation?

After I graduated, I spent about six years working at Philips, I designed lighting for various major chain stores. Alongside this job, I volunteered at the research project Culture Territory: Volkhonka Quarters. I analyzed the lighting environment of the Ostozhenka St. in Moscow; then this data was used by established lighting designers to produce recommendations that will improve the lighting in a Volkhonka quarter. This project considered not only lighting, but other aspects of the urban environment, including traffic, green zones, and the history of the place.

At that time I also met Natalya Bystyantseva (an associate professor at ITMO’s Institute of Design and Urban Studies – Ed.). She recommended I apply for a PhD program at ITMO so that I could continue my research. I followed her advice and studied full-time, while also working full-time in Moscow – I traveled back and forth between the cities, took more vacations or worked online, so that I could pass my exams on time. This was all made possible thanks to my supervisor Konstantin Kuznetsov – without his support and understanding I would have a hard time trying alternative approaches in my work. In the middle of my PhD, my first daughter was born and when my maternity leave ended, I decided to change my career path: I became a lecturer and researcher at ITMO.

How did you make this decision?

When I lived in Moscow and had to provide for myself after my Master’s, I didn’t think it possible to earn a living doing science: I had to pay rent, eat, travel, and cover other expenses. That’s why I chose a career that would help me make enough money. When I met my future husband, he showed me that it could be different – he is a materials scientist and he proved to me that research can truly make good money. For that, however, you need to know where to look for grants and how to apply for them; you also have to be able to work on several projects at once.

I was also motivated by the birth of my first child. I wanted to do something meaningful and promising for the future and my children.

Svetlana Roslyakova with family. Photo courtesy of the subject

What projects have you worked on at ITMO?

I love studying how lighting can affect our mood and productivity, so that’s what I continued doing at ITMO. First, I decided to see if office lighting can be used to improve productivity. In this project, I worked with different people from ITMO – my students (Anastasia Lakshina, Tatiana Bragina, and Tatiana Zemlyanova), Olga Gofman (a psychologist and senior researcher at the Research Center “Strong AI in Industry” – Ed.), and volunteers. At a coworking, we installed a dynamic lighting system that changed light temperature and brightness according to certain parameters. In three Master’s theses, we used the same space to study various aspects of both lighting and how it affects our psychophysiological state.

As a result, we discovered that lighting can improve our productivity by 10-15%. For instance, under neutral white light (4,000 K) our volunteers were equally productive. It’s not advisable to use cold (over 5,000 K) or warm (less than 2,700 K) lighting for longer periods of time, but they could be combined to improve a person’s psychophysiological state. At the start of the day and after lunch, cold light improves productivity, while before lunch and at the end of the day, warm light has a rejuvenating effect. I have to note that these effects of lighting were only present if the volunteers didn’t have chronic fatigue, depression, burnout, or other conditions.

Read also:

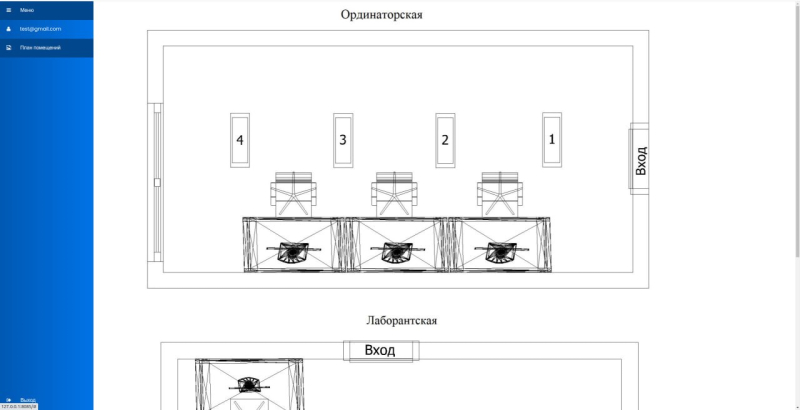

Our research got the attention of medical professionals from Pavlov First State Medical University of St. Petersburg. They have 24-hour working days, which is exhausting. In order to improve their working conditions, we decided to adjust lighting in the university’s clinic (this was the Master’s project of Daria Klimova). First, we analyzed the existing system. The lighting didn’t meet the state standards, so our first step was increasing brightness. Surprisingly, the clinicians were so used to dimmed light that they considered the one that met the standards too bright.

Next, together with the clinicians, we set about selecting the most comfortable lighting for irregular working hours. We then gave total freedom to the employees to choose the lighting, and we didn’t offer any instructions on the effects each change in lighting would have. At every stage, we used psychological methods and biomonitoring data (pulse, sleep, and activity) to observe changes in the clinicians’ state. The main difficulty was that radiologists and lab technicians were working during the experiment, so we had to do our best not to interrupt them. That’s when we teamed up with the neurotechnologies specialists at ITMO and namely Master’s student Marina Shadus, who helped us develop and algorithm to measure productivity based on pulse.

In this project, supported by a Russian Science Foundation grant, we developed personalized psychological recommendations for clinicians on maintaining their well-being and suggested an adaptive lighting system for 24-hour work shifts. With the system, you can use an app to regulate color temperature and brightness in a room based on requests and well-being of people inside it. In the nearly year-long experiment, we discovered that 90.9% of our participants preferred adjustable lighting to static. 72.7% of our respondents also shared that the new system had a positive effect on their comfort. We are currently improving the project based on feedback from the clinicians.

Svetlana Roslyakova presenting her research at the international conference Lighting Design. Photo courtesy of the subject

Lighting design is no longer just about the utilitarian qualities of, say, desk lamps or outdoor lights. In recent years, many have spoken about the effects of lighting on our lives, comfort, and productivity. In your opinion, what is the future of interdisciplinary research in this field?

The bare-minimum goal of lighting design is to create safe spaces where people can see everything and do their work in peace. Then, it’s important to make a good design for the light object and to integrate it into its environment in a way that makes our surroundings visually pleasing. Of course, I’d want to see more people apply the knowledge that we have about the ways in which light can have a positive effect on human wellness and health, but that’s more of a bonus objective for now.

Just ten years ago, few people paid attention to the link between wellness, productivity, and lighting. During the pandemic, we spent a lot of time at home and, seemingly, realized how light can change the atmosphere and purpose of any space. For instance, you need cool, energizing light in a workspace, but a warmer light in the bedroom where you spend cozy evenings. Light is a flexible tool that helps us maximize the usefulness of spaces.

Right now, we’re developing personalized lighting modes and recommendations on how to use them. We’re also creating algorithms for an automated light control system so that smart home systems can let people tailor the lighting to their needs. I believe that the next step in the process will be the total integration of users’ wellness data into the control systems; this way, the technology will be able to gauge the person’s current state and adjust the light without any user input.

A screenshot of the app that helps adjust lighting at the clinic. Image courtesy of the subject

Last year, you received the KOLBA award (link in Russian) for women in science and tech. It was presented in recognition of your research – including that which you conducted at ITMO. You’re also raising two daughters. How do you combine family life and science?

You have to set priorities – understand what you want from life and when: when to grow as a professional and win grants and when to be with family. Then, you must accept that not everything will be as planned and that’s not something to reprimand yourself over. Some things can be left for later.

Secondly, support from loved ones is important. When I had a lot of grant-related work, my husband supported me and took on more responsibilities at home. While I was at a conference in St. Petersburg, he’d take our six-month daughter on walks in the Summer Garden. It works both ways – when he needs to meet the deadline on a paper, I’ll spend more time with the kids. And, of course, grandparents come in clutch.

Finally, it’s important to take breaks. I love to travel and see new places, so I try to change my surroundings often.

Svetlana Roslyakova at the KOLBA awards ceremony. Photo courtesy of the subject

But, unfortunately, women often have to make a choice between career and family.

I think that any kind of career will conflict with family life, and it’s also impossible to be the perfect mom, no matter what field you work in. But that’s not necessary, either – it’s enough to be a good mother and not stress about the little things. Work gives me the ability to switch gears, grow, and talk to other people. I have experience to compare – my first maternity leave was the classic Groundhog Day-esque deal, filled with everyday chores. Now that I’m on my second one, I try to combine work life and home life. Psychologically, for me, it’s easier that way: science gives me a break from home routine, but my family inspires me to keep working.

It’s important for women to have the ability to combine career and family. It would help, for example, if universities would provide kindergartens for all – students, postgrads, and staff. It’s also crucial to provide sufficient material support to parents, especially when the kids are young. This support can fulfill the family’s basic needs and make the parents feel safe. Every woman decides for herself how to live her life, but she must have the opportunity to have both a career and a family.