Andrey Kuznetsov has a PhD in sociology, and is an associate professor at ITMO University, research associate at the STS (Science and Technology Studies) Center of the European University at St. Petersburg, and also head of ITMO’s Science and Technologies in Society Master’s program.

Car dependency

We live in a world where cars take pride of place: the majority of cities are car-centric, while others are car-dependent. Their infrastructure and interests are dominated by road junctions, roundabouts, and parking lots.

It’s not the done thing to discuss this widely, as this is perceived as a given, but the existing car-focused system is unacceptable. Here are its main weak spots:

- it’s not environmentally friendly;

- it’s not people-friendly: in Russia, some 18,000 people die in traffic accidents each year, and another 200,000 are injured. Cars take away not only health but also time: over their 240 workday period, Moscow residents spend 91 hours a year stuck in traffic jams (second only to Los Angeles). For St. Petersburg residents, this number is 53 hours. And these are just traffic jams – not including the actual time spent on the road;

- it’s unethical: cars, often plural, are a prerogative of the rich; at the same time, they’re often parked downtown, occupying and polluting public spaces. A good example of this is Los Angeles, 24% of the territory of which accounts for roads and parking lots, and the construction of road infrastructure is causing the destruction of urban communities.

On the one hand, a car means speed and convenience, but on the other, it’s crazy ineffective in traffic jams. We’d like to imagine life without cars or with better kinds of cars but we’re afraid to – which explains the fear and fascination evoked by the idea of a self-driving car.

The very notion of it enraptures people, gives them hope for more secure, comfortable, and effective transportation – no traffic jams on the roads, less harm to the environment. That said, as of now, self-driving means of transportation are more than anything a source of fear. Because urban life is car-centric, and radical innovation in this field can lead to unpredictable changes in the organization of our day-to-day lives, affecting the economy, information security, legal regulation, and other areas.

Self-driving transport isn’t a figment of futurologists’ imagination, but a real-world technology in which IT companies, car companies, platform businesses, and car-sharing services are all involved. Ideally, driverless vehicles will eliminate exclusive car ownership, which will reduce cars’ environmental impact and make driving accessible to everyone. But in reality, self-driving transport will be subject to many technical and infrastructural questions.

Philosophy of mobility

Philosophy is not a way to solve questions, but a way to identify problems.

Elon Musk’s ideas could be interesting when talking about cars of the future. He once claimed that about 95% of all road accidents are caused by people and not technology. Musk emphasized that the worse we speak about self-driving cars, the more people we thus kill. This is a philosophical statement. Elon Musk’s words are aimed at detecting a problem that wasn’t picked up on before.

Let’s take a closer look at self-driving cars: what is their task, and are they really that “self-driving”?

At the automotive industry’s onset, manufacturers faced the problem of motion: how to put a car in motion without resorting to the muscle power of animals or people? Now, the developers of self-driving cars face the problem of driving: how to replace a human driver with a non-human one?

Strictly speaking, “self-driving” cars don’t drive themselves. They are driven – just not by humans but other entities: artificial intelligence algorithms, cyberphysical devices, sensors and digital infrastructures. But if we develop that thought, it can be stated that modern cars are close to that too – they’re embedded with so many advanced driver support components that we can hardly say that they’re 100% driven by humans.

Another myth is autonomy. Of course, self-driving cars don’t require your direct involvement in the driving process, but in reality modern transport is no more autonomous. Unlike their predecessors, self-driving cars will be more dependent on their infrastructure and the institutions that service it. And this isn’t just about gas stations, roads, and car repair shops, but also digital maps, databases, satellite communications, new safety protocols and regulatory standards.

Smart cars

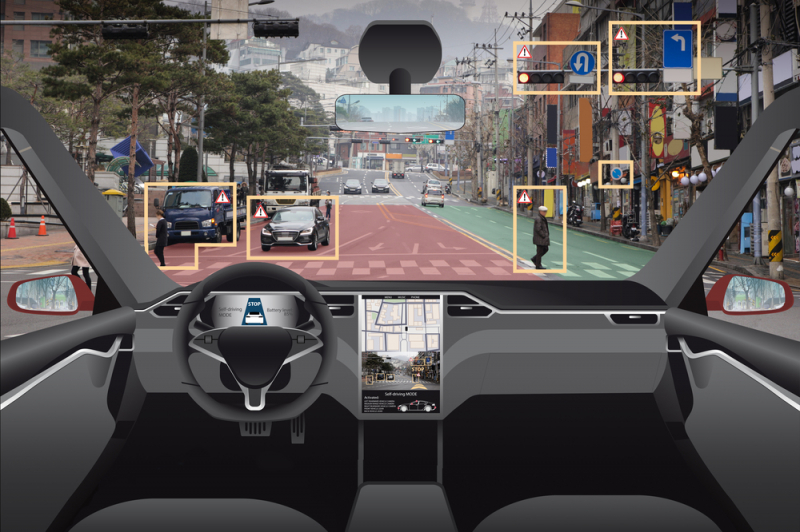

The goal of self-driving car manufacturers is to create smart technology which would handle the task of driving without, or better than, humans.

When we’re talking about smart technology, it all boils down to precision, to its efficiency. But smart also means teachable, consequently, self-driving cars will also need to learn. And since learning comes hand in hand with making mistakes, it’s important to understand what they’d look like with cars. While conventional software slips manifest as malfunctions, loss or leakage of data, smart car software mistakes result in accidents.

A notable example of algorithms and deep machine learning failure happened to a self-driving car by Uber. In March 2018, it knocked down and killed a pedestrian, Elaine Herzberg, who was crossing the road outside of a designated crosswalk, at nighttime, whilst also pushing a bicycle before her. The image of a person crossing the road next to a bicycle turned out to be too difficult for the algorithm driving the car to process. It only recognized Elaine as an object crushing into which would be dangerous when it was already too late. Having done that, it did signal the car to perform emergency automatic braking, but Uber’s security engineers had disabled this feature the day before due to a potential hardware conflict. Why?

It was because the algorithm gave out a lot of false-positive responses. And shouldn’t there have been a test engineer in the car? At the time of the accident, an Uber engineer was there, but despite the instructions, they watched a music show on their tablet for most of the commute and didn’t have the time to react to the pedestrian being there.

This example not only demonstrates the internal complexity of the process of teaching smart cars, their developers, and users, but also raises the question about safety in the context of the IT and automotive industries coming closer together. Essentially, this represents the convergence, the unification of different, sometimes even diametrically opposed, features in one device. It could be said that we’re getting closer to driving on smartphones, and this would in part be true.

When it comes to safety, as cars get smarter, they can paradoxically become less reliable. From the automotive industry’s standpoint, they can maintain their level of reliability, but as far as information technologies are concerned, they can’t. With the introduction of complex software to cars comes the possibility to remotely break into them, steal them, program them for a road accident, etc.

Consequently, in addition to technological safety, a smart car should also be resilient to cyber threats. This isn’t the only aspect that is to change if a vehicle becomes self-driving. Another one is the attitude to software bugs, which before used to refer to regular mistakes. Now, such a mistake can result in the loss of human lives – and this can hardly be called a bug.

By and large, it’s hard to imagine how a union between automotive concerns and IT companies – two different worlds – would come about. In the eyes of the automotive industry, a car is a finished product. If a defect is detected, the manufacturer recalls the product from the market, suffering serious losses as a result. That’s why the industry approaches product development very carefully.

In general, what IT companies sell isn’t finished products but services (software). Their response to detecting a bug in their software would be to release an update or a bug patch. These are two different business logics which have to do with two different state regulatory regimes, and it’ll be very interesting to see how they will manage together.

Andrey Kuznetsov’s lecture was held as part of ITMO’s Center for Science Communication’s Scicomm Cocoa Talk series.