The black soldier fly is the species most popular for breeding that is also safest for humans. In artificial conditions, a single adult fly can produce 500-600 eggs that turn into larvae in 25 days. It is the larvae that are considered the most valuable in this case, as they are capable of turning organic waste into useful products. Apart from adult black soldier flies that survive on only water, the larvae can feed on expired products, food and agricultural waste, activated sludge (the product of water purification), as well as waste from meat, fish, dairy, and beer industries.

Thanks to this diet, the larvae contain chitin, a compound used in medicine and food industry; they also produce a natural fertilizer, biohumus. Once they’ve gained weight, the insects are dehydrated and processed into a powder with a high protein content. The lipids gained in this process are used as biodiesel and palm oil substitute in cosmetics, while the defatted protein concentrate is used as alternative feed for cattle, poultry, and fish. While only 70-80% of protein from traditional sources, such as soybeans, corn, clover, and peas is digestible, for protein derived from larvae the percentage is 90. Moreover, it contains amino acids beneficial for the nervous system, hair, and protein processing, such as tryptophan, phenylalanine, and methionine.

Black soldier fly larvae. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

However, in order to breed larvae and then turn them into a biomass with a dependably high content of valuable nutrients, it is necessary to secure ideal conditions and substrate (the larvae feed medium).

“There are several challenges in terms of breeding larvae. For instance, adult flies may not reproduce, the eggs they lay may not turn into larvae, or the larvae may contain different levels of proteins and lipids because one part of them ate brewing waste, another – chocolate, and the third – oranges. How can we make this process controllable and technological? How can we ensure that all larvae contain the necessary amount of nutrients and have this technology require less than a dozen professionals on site? These were the issues we addressed in our project,” says Nelli Molodkina, an associate professor and head of a laboratory at ITMO University’s Faculty of Ecotechnologies.

Nelli Molodkina. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

After three years of research, the faculty’s scientists have developed a list of requirements for substrates necessary to ensure larvae growth, as well as criteria and procedure for quality control of high-protein biomass at every stage of development. According to the researchers, even the size, porosity, and nutrient ratio of substrate’s components can have an effect on the quality of resulting biomass.

“We placed larvae into various substrates and observed their behavior and biomass. The concentration of proteins and lipids is highest at the early prepupa stage – that’s when it’s best to process the larvae. It also turned out that a substrate’s ingredients have an effect on the amount of lipids and proteins in the resulting biomass; this means we can adjust this parameter in order to get the product with the desired components. Typically, larvae have 35-40% protein contents. In order to bring it up to 60%, the substrate has to contain bread waste, such as dried bread or bran,” adds Anastasia Gorbulina, a second-year Master’s student at the Faculty of Ecotechnologies.

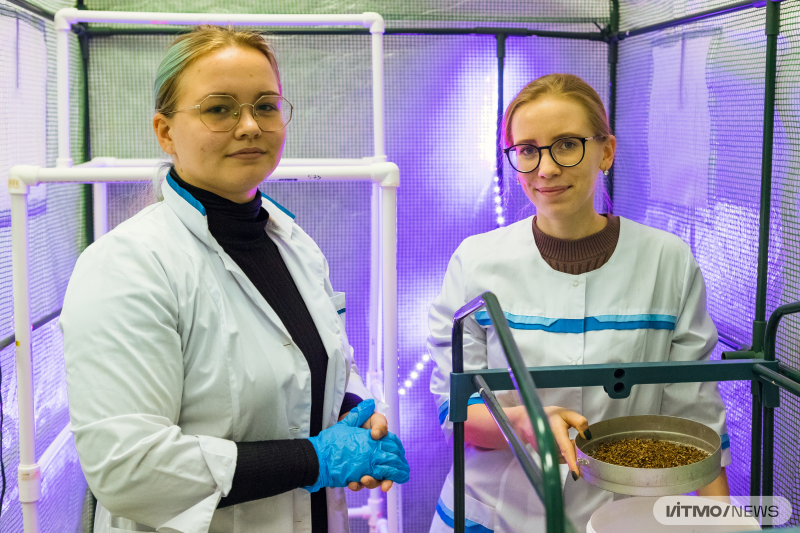

Alisa Pismennaya and Anastasia Gorbulina at the lab. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

In the future, the scientists are planning to mix the substrates that showed the best results with other waste (fruit, vegetables, and beer waste) and conduct an additional series of experiments. This way, they will be able to analyze the insects’ reaction to new feed and optimize the substrate’s components in order to ensure an even higher protein percentage in the biomass. Moreover, the research team is on the lookout for industrial partners to scale the larvae breeding technology.