Fantastic beasts and new monopolies

In the business and financial worlds, a unicorn refers to a privately held startup company with a value of over $1 billion. These are, for example, Uber, Airbnb, WeWork, SpaceX, and Juul.

Unicorns appeared 18 years ago. Before this, no entrepreneur sought to grow their company to a billion in revenue. They used to launch their projects, observe their rapid uptake, and then sell half of their portfolio to good managers. At that time, it seemed more reasonable and profitable than waiting for major corporations to attack their startups.

Why has everything changed? After a high-profile accounting scandal with Enron (depicted in the 2005 documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room), the US federal government decided to impose control over startups. Until then, many companies resorted to IPO (Initial Public Offering – Ed.) withdrawals but new restrictions made it problematic and unprofitable. It became much cheaper to scale your business and then sell it to some strategists bypassing IPOs. Basically, unicorns appeared because officials began to take over business.

There are two key reasons why people appreciate unicorns: firstly, they come up with unique and innovative tech solutions that large companies would never create and, secondly, they are monopoly killers (that’s why economists love them, too.). For example, Uber and Airbnb have developed a completely new sharing economy, namely, asset sharing.

The problem with unicorns is that they are just new versions of major corporations. When we think of startups, we imagine an energetic person, who creates something and achieves great results.

While corporations make us think of perfectly oiled machines; they seem to work stably but they don’t give us anything new and at the same time their employees are climbing up the corporate ladder for years with no freedom. But if we look at today's giant startups, we will see the same features of monopolies that will inevitably turn into corporations.

Innovation vs expertise

As a lecturer, I am concerned that students are inspired by the success of startups and are looking for opportunities to make a load of money. But we explain that startups are not about the money but about innovation. Many think that it is easy to become an innovator – just call yourself one. But, in fact, it is a long process of gaining expertise in the problems of your consumers, technological solutions, and project management. Moreover, it is crucial to simultaneously develop in all three fields.

Even if you manage to grow to a billion dollars without figuring out the demand and the technology, your startup is doomed. It is worth remembering Theranos; it is a classical case of a company that understood the consumer problem but not the technology, thus, underestimated its complexity, and saved on scientists (check the 2019 documentary The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley).

On the other hand, we have the Evernote application, which was developed by one of our brilliant compatriots, Stepan Pachikov, a leading expert in handwriting recognition. He wanted to apply the same technology in a service for storing notes, so he worked out an idea and sold it to investors. This idea was to develop a cloud, which people could use to write reminders, as well as save receipts and labels from wine bottles. But the technology has not found its audience, and competitors are actively undermining it. As a result, the company that used to cost $3 billion is now losing money.

I suggest paying equal attention to understanding customer problems and mastering the technology. The worst thing happens to those people who call themselves innovators but have no idea about what problem they are trying to solve and with what possible methods. The same goes for those who know the problem but do not have the technology. Unicorns are people who have both in their hands.

Cargo cults and the Plunge method

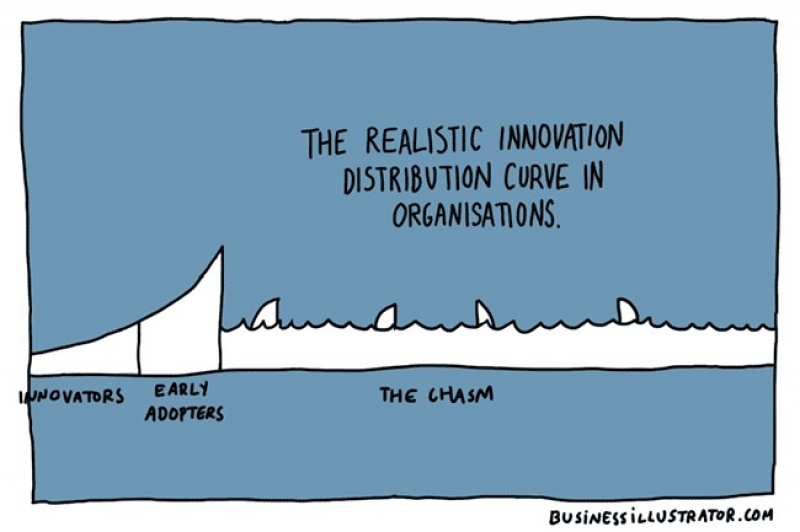

There are two key challenges with innovations, which we often observe at Skoltech. The first one is playing in science. Peer reviews are essential in academia but they may lead to cargo cults. When discussing an innovative project, people cease to understand the reasons behind the science; they come simply to say something that gains praise and approval from other scholars. Such tendencies in no way can result in innovation.

Another cargo cult is called the Great Gatsby. There is a whole group of people who believe that if they keep attending various meetings, conferences, and meetups, they will have the necessary contacts and understanding of the problem, and thus become unicorns.

There are also people who, for instance, work on something in their garage and do not show it to anyone, and when they do, their technology turns out to be no longer relevant or needed.

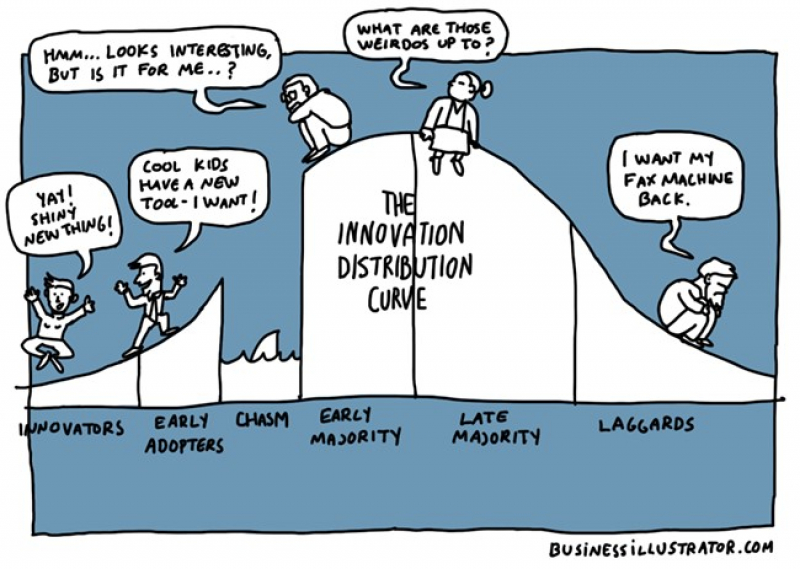

Of course, there could not be any ready-made formula for success as it must include a customer who might not know what they want or cannot explain it. Moreover, customers are prone to change their mind: they thought that they needed this product but now they do not think so. People often think of a new product launch as a path from failure to success. But in most cases, it feels more like a very long and exhausting process.

At Skoltech, we came up with our own methodology for hypothesis testing and project work. We perfected it for seven years but initially were not certain that it would work. But we have managed to create a startup funnel, which allows students to demonstrate their ready-made prototypes, receive funding, and develop quite successful projects in the future.

We took the Agile methodology and slightly reworked it by adding engineering and innovation technology specifics. Our method is called Plunge. The key idea is to keep on refining your initial hypothesis through controlled experimentation and work on a product prototype. At the same time, we try to follow a specific approach, establish a dialogue with customers, and focus on the technological side of the issue, namely, the prototype.

Unicorns can appear anywhere

The main feature of unicorns is that they are, in fact, fantastic beasts, which appeared where they simply could not and when no one believed in them or understood them.

I know one of the most vivid examples, although it is not a startup but an innovation produced by a corporation. In 1999, I studied at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, where Jeffrey Bezos once came to give a talk. At that time, Amazon’s worth hit $10 billion, although it traded exclusively in books. This was a classic example of the dot-com bubble that later exploded because of Enron.

Then, everyone was sure that Amazon would be bought by a large corporation, destroyed by its competitors, or crushed by the government. In his talk, Jeffrey Bezos shared his idea of making e-books, and we all thought he was crazy. There were e-books even before Kindle but they were not popular as people still believed that books should only be printed and sold in bookstores.

Kindle did not seem to stand a chance but in the end, it turned the market upside down and created a new reading culture. Jeffrey Bezos’ core contribution is the built-in DRM (digital rights management) for preventing unauthorized redistribution of digital media. He knew that this was the key problem.

It seems that such stories can happen only in Silicon Valley and not in our country. But I will tell you another story that proves that it can happen in any place on Earth.

The first Skolkovo unicorn was the Hepatera company, which develops an innovative drug for hepatitis B and D. When they only started in 2010, we did not believe that they would find customers. However, we were proud of the scientific component of this project. Then, hepatitis B was considered cured and vaccinated, and hepatitis D – extremely rare. Nevertheless, the project’s team received a large Skolkovo grant in 2014 and started clinical trials. Despite the successful results, the company could not find investors for a long time and eventually moved to Germany.

During these ten years, they had been a small startup but in late 2020 they were acquired by the American Gilead Sciences for 1.5 billion euros. Even though the project was partly German, it was a massive achievement for the Russian pharmaceuticals market. The European Medicines Agency approved the results of clinical trials; the expertise remained in Russia and patients can use this drug in their treatment.

There are also other highly successful startups in innovative pharmaceuticals and digital medicine: Botkin.AI, a platform for diagnostics and risk analysis of disease development using AI, and Genotek, a DNA analysis service, both have already entered their first IPO. And we should not forget Sputnik V and its success, as well as Pharmadiol, the world’s first patented anticoagulant for COVID-19.

The full version of Prof. Dmitry Kulish’s lecture is available here (in Russian).