“I went to get bread in the city, as they didn’t bake bread in Lesnoy (a historical neighborhood on the northern side of St. Petersburg – Ed.). There wasn’t any firewood or water. I reached the Vyborg Side. On the way back, I fell several times and slowly got colder. I got to the market and met Alka – my friend. He helped me get up and walk to the Svetlana factory. I warmed up in a shed and kept on walking home. In a ditch, I fell and nearly froze, but Mom was walking by and brought me home. On that same day, at 14 hours, Dad died sitting on the bed,” wrote in his journal Kolya Vasilyev, an 11-year-old boy living in the besieged Leningrad.

This and 600 other diary entries written by citizens of Leningrad are stored in the digital library (link in Russian) of the Prozhito (“Lived Through”) center. As the project’s authors note, they have been able to assemble the most comprehensive bibliography of diaries from wartime Leningrad.

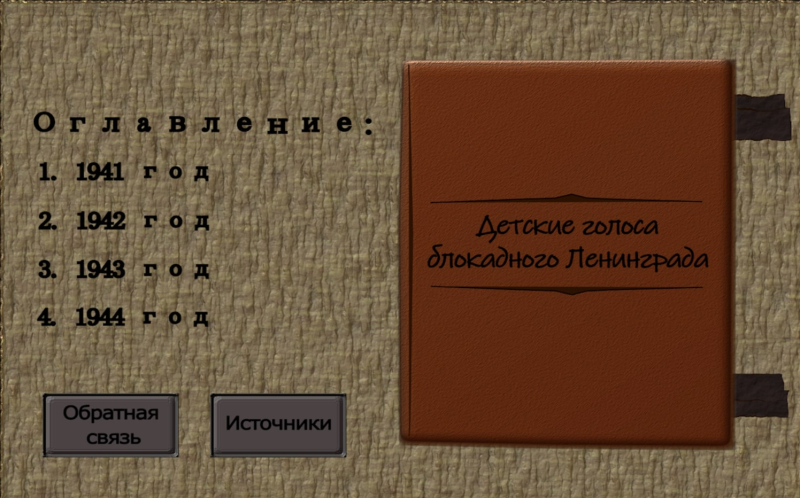

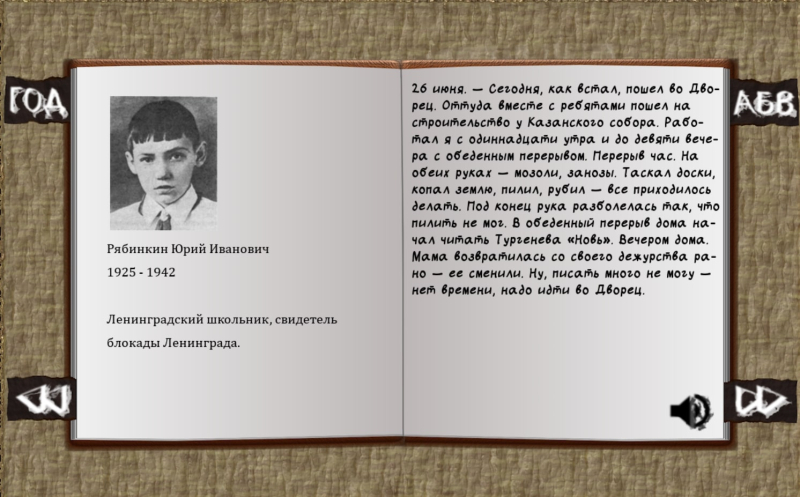

Based on these historical documents, as well as books and scientific papers about the Siege of Leningrad, students from ITMO University have established their own project called Children’s Voices of Besieged Leningrad. Stories Left in Diaries. The app relays the stories of Leningrad’s youngest inhabitants and allows users to listen to them in audio form and see historical events through children’s eyes. As of today, 37 out of 80 diary entries – made between September, 1941 and January, 1944 by kids and under-18 teens – have been processed and are being uploaded into the app.

“What do kids usually look like? They run around outside, play games, and don’t have a care in the world – because they are protected from its issues by adults. But the horrible events of the Siege of Leningrad affected everyone, including kids. In their journals, the thoughts they share are far from childish; they describe the German invasion, the hunger, the cold. Reading these entries evoked incredible, indescribable feelings in me. I understood that others, too, must have the opportunity to read these diaries and feel every word,” says Alina Fedorova, one of the project’s co-creators and a first-year student at the Faculty of Software Engineering and Computer Systems.

Alina Fedorova. Photo: Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

On the architectural side, the app was developed by Aleksandr Kolesov, a first-year student at ITMO’s Game Development School; Alina Fedorova was responsible for the design; and Nikita Mikhalev, a second-year student of the Information Technologies and Programming Faculty, sought out voice actors and processed audio files. The project was curated by Dmitry Vycherov, a historian and senior lecturer at the Faculty of Technological Management and Innovations.

“We designed the app to resemble a diary. You can flip through the pages, read the entries and descriptions of the authors, and see their pictures. In addition, we had professional narrators record the audio versions. As a result, readers can explore these memories both visually and through recordings,” explains Alina Fedorova.

Work on the project continued for around seven months. The app is already available for downloading via GitHub. But the developers aren’t moving on just yet. Now, they plan to add more diary entries, complete with audio, and include a search feature based on keywords and historic events.

Children’s Voices… isn’t the only project by ITMO students that focuses on the history of the Siege of Leningrad. Earlier on, another student team collaborated with the Prozhito project to create a digital map of the city with geotags sourced from wartime diaries. Together with researchers, the authors analyzed 500+ entries to visualize the life of Leningrad in the 40s. The map contains descriptions of specific neighborhoods and time periods, as well as testimonials from citizens of various ages.

Also, in 2024 ITMO students developed an interactive map for the Museum of Partisan Glory in Dedovichi (Pskov Oblast), tracing the route of a legendary supply convoy that traveled over 100 kilometers along the frontline, bringing more than 40 tons of supplies to besieged Leningrad in March, 1942.