The festival lasted 12 hours – from midday to midnight. This wasn’t just a conceptual idea but also a somewhat forced decision as all the invited experts live in different time zones, with a 13-hour time difference for some. The online format united three continents and six time zones, which turned out to be a literal manifestation of the festival’s main topic – matters of distant telepresence and infrastructures that make it possible. Participants discussed how communication practices changed and how people’s connections with each other transformed with telecommunication systems and online communication opportunities entering our lives.

The festival’s participants

Participating in the festival were key figures of the Art & Science scene: Stelarc, legendary artist and performer, one of the pioneers of science art; Ken Rinaldo, interdisciplinary artist and professor at the College of Arts & Sciences at The Ohio State University; Maurice Benayoun, French inventor and media artist; William Uricchio, media scholar and professor of Comparative Media Studies at MIT; Frederik de Wilde, Belgian interdisciplinary artist; David Bowen, artist and professor at the University of Minnesota, and many others. The festival’s program included talks from these well-known speakers as well as two art films: Welcome to Erewhon, a loose adaptation of a philosophical fable published in 1872 by the British writer Samuel Butler, and Khoreku. The stories of the Tuhard tundra, a multimedia anthropological VR art project by young media artists Anna Tolkacheva and Andrey Nosov. By way of the culmination, there was a generative music performance by electronic musician and coder Renick Bell.

Problems of telepresence

The main question the organizers put forward to the participants was how social structures, art practices, human sensuality, and in general the reality of our existence have changed in the current situation, and what awaits us in the future. According to the curator Natalia Fedorova, in essence this was an attempt to take stock of three months of isolation and the forced global shift to the online it caused.

“This was a check-in on how we feel in this situation that none of us expected – this situation of complete physical disconnection combined with absolutely unprecedented opportunities for telepresence. It becomes clear now that all cultural events in the six months to follow will swap their traditional international format with the format of international telepresence. This raises questions, on the one hand, about the degree of these events’ realness, on the other – about how to increase this degree of realness. In its turn, this leads to another question: whether all this telepresence we’re talking about is presence over a distance, or is it a form of absence in the place you’re currently in. Where am I really when I’m participating in a Zoom conference? Where does this energy, feeling, living human aura go – where is it at as I send it out through the means of telecommunication? In the wires, in the Hz space that unites different electronic devices?” ponders Natalia Fedorova.

The future of telehaptics

Telehaptics is a term that describes the ability to exchange touches and sensory experiences using computer technologies and opportunities presented by internet communications. We’ve long become accustomed to communicate with each other over distances – modern technologies effectively allow us to fully live the experience of “presence in absence”. We’re constantly in touch through voice and video calls, we can broadcast everything that happens around us – and transmit it over distances in the blink of an eye. But what to do with tactile sensations? The situation brought by the pandemic – where our tactile contacts were limited by new personal safety rules – have broached the issue of the necessity of technologies for transmission of handshakes, kisses, hugs.

This was the topic of the presentation by Satomi Sugiyama, professor of Communication and Media Studies at Franklin University Switzerland. She spoke about her research on how the appearance of mobile phones – and, later, social media and messengers – has brought about a sea change not only in our communication with each other but also our perception of reality at large. How, under the influence of technologies, we moved to the state of constant communication with people all over the world, permanent access for all, the blurring distinction between public and private, and how mobile devices literally became a continuation of our bodies.

The researcher also shared her developments regarding the future of various devices for the transmission of tactile sensations over a distance. Currently, there are several prototypes of such devices on the market, for example Hug Shirt – for imitating hugs, and Kissinger – for distance kisses. A small research conducted by Satomi Sugiyama, which involved surveying 60 people, most of them under 30 years old, showed that for now, people aren’t fully ready to embrace such devices. They see these interactions not only as unusual and unnatural – but also as more divisive and amplifying the sense of isolation from loved ones. But the perception of such devices can change as soon as in the near future.

Deep-dive into the history of the matter

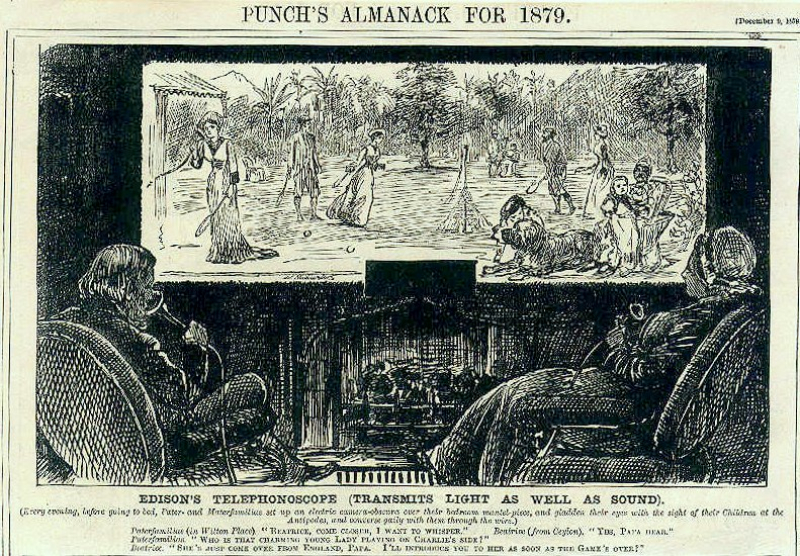

Discussing the topic of how people perceived and were getting used to new communication technologies at the very start of their development was William Uricchio, a MIT and Utrecht University professor, principal investigator of the MIT Open Documentary Lab and Co-Creation Studio, and author of numerous publications and books on new media. He explored the history of the matter, showing how the future of communication was depicted on the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries. The invention of the telephone in 1876 was almost immediately followed by the emergence of the concept of a telephonoscope – a videophone with a large screen that would transmit light and sound. Though this invention wasn’t brought to life, the idea behind it, embodied in many drawings, for example ones by George du Maurier and Albert Robida, for a long time gripped the minds of people of the past and raised a lot of epistemological, ontological and ethical questions. People didn’t understand whether or not the train in the famous film by the Lumière brothers was real, believed that radiofrequency noise (and later, white noise on TV) hid the voices of the dead, and that a TV could steal their soul. The most surprising thing is how most predictions by science fiction writers of the time, when it came to communications, ended up being brought to life and becoming a part and parcel of our everyday existence.

Internet as a neural network

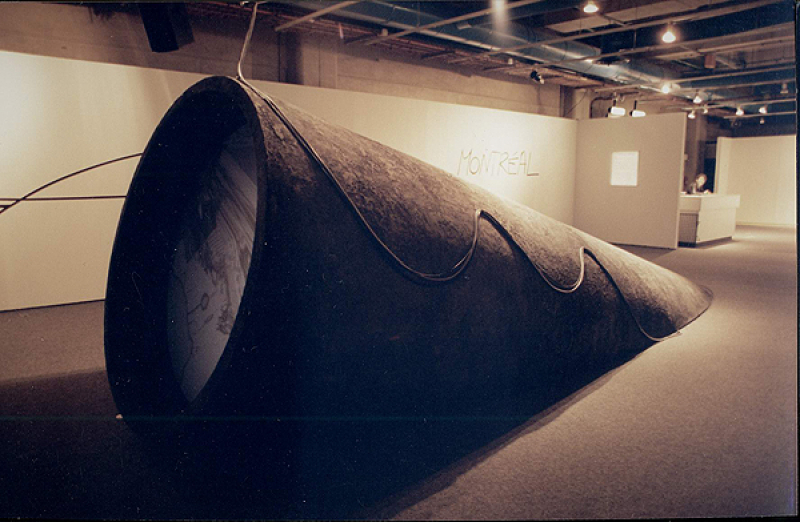

Also speaking about his projects in the field of internet communication and virtual reality was Maurice Benayoun, French artist, researcher, staff member of the School of Creative Media at City University of Hong Kong, and head of Creation Interactive Transdisciplinary Universitaire Laboratory at Sorbonne University. His first projects were implemented in the middle of the ‘90s, when the idea of direct video communication over large distances was still a novelty. For example, his 1995 work – a virtual transatlantic tunnel connecting Centre Pompidou in Paris, France and The Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal, Canada – is considered to be the first intercontinental televirtual installation. Visitors were offered to go through the extremely long virtual tunnel the walls of which depicted key art objects of the two countries. Occasionally, people from Paris and Montreal would bump into each other on the way and talk through a video call.

From the very start of his art career, Maurice Benayoun has been focusing on critical research of mutations in modern society, caused by the recently introduced technologies. His main concept is that the internet isn’t just some virtual public space, but a worldwide neural network where each of us is akin to a nerve ending. In other words, we not only share this virtual space with each other but also fill it with our emotions, feelings, and concepts – and experience it first-hand.

Holobiont and cross-species interaction

The idea of symbiotic connection – between people, technologies, and all living organisms on Earth – is also developed by Ken Rinaldo, a world-renowned interdisciplinary artist and professor at the College of Arts & Sciences at The Ohio State University. In his works, he questions the notion of personality and individuality, positing that at the end of the day, we’re just a set of bacteria and viruses housed in our bodies. Even our feelings, emotions and sensations can be thrown into question, as they can be artificially generated and staged with the help of technological devices and cognitive illusions. Ken Rinaldo views the world as a holobiont, and people living in it as either parasites or symbiotes.

Other living beings have the same right to freedom of the will as humans do, believes Ken Rinaldo, which is why a lot of his experiments focus on embedding robotic devices in biological structures and systems. For example, he uses tech to try to interact with gut microbiome (the Enteric Consciousness project), or gets Siamese fighting fish to manage a robot (the Augmented Fish Reality project). In his later works, the artist researches cross-species interaction between humans and biomorphic robots (the Fusiform Polyphony project).

Robots as continuation of humans

Initially, human-robot interaction was supposed to be the festival’s main topic, but it was replaced at the last moment with a more relevant one. This notwithstanding, it wasn’t overlooked, as many of the invited artists have long been using elements of robotics in their works.

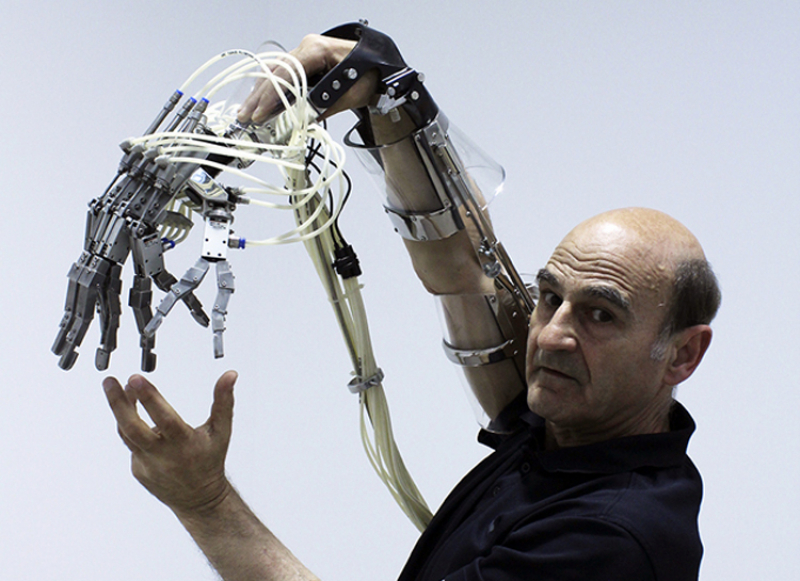

For instance, the star of the Art & Science scene – Cyprus-born, Melbourne-raised artist Stelarc – is known not just by growing a third ear on his arm, but also by his performances, in which he uses robotic and electromyostimulation devices for studying the ways of interacting with the body. His main works in this regard include the project Third Hand, implemented back in 1980, Fractal Flesh, a 1995 performance spectators of which could remotely control the artist’s body, and 2002 Movatar, in which the artist’s movements were commanded by randomly generated artificial intelligence sequences. His main message is that humanity is long overdue for a review of the concepts of identity and subjectivity, as well as the relationship between the body and increasingly more complex technologies: what possibilities lay before the human body, and what subjective experience can be born from such interactions.

The topic of industrial, applied robotics was also touched upon by such experts as Dominik Bösl, professor at the Hochschule der Bayerischen Wirtschaft in Munich and founder of the Robotic Governance project, who took a look at the past and future of robotic devices. Alexander Kapitonov, dean of ITMO University’s Faculty of Infocommunication Technologies and associate professor at the Faculty of Control Systems and Robotics, founder of the projects Robonomics Network and Airalab, talked about the concept of independent autonomous robot economics – illustrating this with the example of a robot artist developed by the team from ITMO’s Faculty of Control Systems and Robotics – as well as opportunities of using autonomous robots for monitoring and regulating economic problems.

In his turn, Vladimir Belyy, head of the Alpha Robotics Venture fund, discussed how robots are used in the film industry and can be applied in the creation of art objects.

Results of the festival

Despite the challenges in adapting to the new format, the entirety of the program held up with almost no alterations. More than 25 participants spoke live, while the final performance was pre-recorded because the musician Renick Bell is currently in Tokyo, where it was early morning when the festival was ending. All in all, though the idea to hold a 12-hour marathon sounded crazy, according to the organizers themselves, it turned out to be more of a successful experiment.

“We planned to hold this festival in April and invariably offline, but the circumstances changed. This crazy idea to have it go on for 12 hours occurred very spontaneously, spurred by the fact that one of the participants, Stelarc, is in Australia, which is seven hours ahead of St. Petersburg. Ken Rinaldo is in Ohio, where the time difference is minus seven hours. Between them, they have almost a day of time difference. It turned out that all speakers were from completely different time zones and it was necessary to bring them together somehow. I’d also like to note that when we invited Ken Rinaldo, he responded that he remembered ITMO University, its historical building, museum and his tour with the rector well, which was very unexpected and nice to hear. In February 2017, Ken Rinaldo visited ITMO and spoke at the Hermitage as part of the Art & Science: Science. Art. Museum project,” shares Aliya Sakhariyeva, head of ITMO’s Art & Science Center and the festival’s co-curator.

You can watch the full broadcast of the festival here.