What are the Council's tasks?

The Coordination Council works on a wide range of problems that mostly have to do with improving the working conditions of young scientists. For instance, last year we participated in developing Russia's strategy on research and technology advancement; the Council made some important amendments that became part of the strategy's final version. And recently, we took part in introducing presidential decrees which allowed to organize several new contests aimed at supporting young scientists. Members of the Council were invited to discuss the contests' rules, and corrected them in such a way that they corresponded to the realities of modern research activity and focused on supporting the best of researchers who already showed outstanding results.

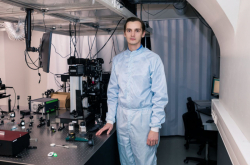

Aleksandra Kalashnikova

Aleksandra Kalashnikova

As a scientist and the Council's deputy chair, which problems of modern science do you find most pressing?

Well, there are many problems, but I would like to point out some of them that have to do with young scientists in particular. As of now, we're reorganizing PhD programs and the process of thesis defence. In general, it is becoming more strict, which, I believe, will do good for science in Russia; yet, there are also changes the sensibility of which I doubt.

Yes, there was that proposition to admit degrees based on publications in prestigious magazines, without even defending a thesis...

The question is how these changes will be carried out. For instance, if we take the problem with thesis defence, the thesis is not always a good estimate of the candidate's level. A lot depends on the qualifying committee.

Yet, I wanted to note one tendency that makes me worry. It seems that the Ministry of Education and Science sees PhD students as just regular students who are a bit older than most. Currently, the Ministry is increasing the number of academic hours for PhD students and is planning to introduce additional examinations. I believe that is a wrong decision. In our laboratory, and in many laboratories I know of, PhD students are the core workforce, they are not students but full-fledged researchers who just need some guidance. They spend a lot of time in their laboratories and have the same responsibilities as their older colleagues. That is why our educational system has to reconsider their role. For instance, in Netherlands where I got my PhD they don't have such a term as "PhD student": they call it "research associate in training", meaning someone who already does research and is currently defending their theses.

What can be done to change the status of PhD students in Russia?

We should create such conditions that PhD students would get sufficient pay for their work. Many laboratories use grants for that, and that might be the proper way. Also, PhD students should be provided with the same social guarantees as research associates. As of now, PhD students that study on tuition-free basis get scholarships of about 6,ooo rubles, which is definitely not enough for them to be able to dedicate all of their time to research even if they wanted to. In our team, when we invite new PhD students, we begin to think of ways to support them straight away. For that purpose, we use funds from grants - a considerable part of them goes to PhD students' wages. I believe that such a system should be formalized and become a common rule.

How do they solve the problem with PhD students in the Netherlands?

They do as follows: most of the PhD positions are bound to particular grants. Such positions are stated in advance by the project head when they apply for the grant; thus, it is not possible to add a PhD student to a research team unless it has money to pay their wages. I believe that this is an honest and transparent system. Of course, it implies having less PhD students, but the four years of their PhD programs become four years of productive research.

In your last interview, you stated that there was a problem with lack of equipment, so you had to conduct research in collaboration with foreign scientists using theirs. Is this problem solved now?

Yes; for several years it was hard to find money for new equipment. But the situation changed. We now have the Russian Science Foundation; the size of its grants is well thought-out, so if the grant is for three years, that amount of money allows to buy the necessary equipment, support the PhD students and conduct a full-fledged research. By no means we won't stop collaborating with foreign colleagues, but now, I hope, we'll be able to contribute more to such collaborations.

The laboratory Aleksandra Kalashnikova works at

The laboratory Aleksandra Kalashnikova works at

Many express concerns that when Project 5-100 is over, and they'll stop giving out major grants, science will come to a standstill once more, as it takes time, and you can't make a breakthrough after just a couple of years of research...

Surely, research is a process. With time, new tasks emerge, and old ones are corrected. And, surely, there will always be concerns related to financing. In 2013-2015, our laboratory succeeded in improving its equipment, so as of now, we don't really have the need to buy anything expensive. We have our tasks, we have the resources and people to solve them. Yet, we still have to spend money on maintenance and wages. So if financing stops, the laboratories will continue to work for some time, but then halt. We had something similar in the 90’s. Great scientific groundwork had been made in the middle and the second half of XX century, but then came the recession, when we no longer could support the laboratories and follow relevant trends in science.

What are the tasks your laboratory is currently working on?

We have some fundamental tasks, and, with time, newer problems that have to do with fundamental physics emerge. As of now, we don't do any applied research, as we still haven't gotten to this stage. Yet, there are tasks that might once grow into applied ones - for instance, controlling the mediums' conditions by using femtosecond laser pulses. This is most promising in regard to information recording. Whether we'll be able to introduce these new technologies depends on our future results and the keenness of business.

And does the Council solve tasks related to attracting the industry to funding research?

Last year, we tried to define the problems that hinder young scientists' careers. Among other questions, we've raised the one concerning the lack of collaboration between scientists and business. We need companies that are ready to finance long-term projects. Developing new technologies is expensive; universities can bring a research to a certain level, yet introducing a technology implies large investments. Only major companies can afford that, and do we have such companies in Russia? Well, we might have some demand on research in the field of petroleum refining. As for high-technology companies, there are just a few of them.

What about young scientists who work in the regions? Surely, in big cities they have many opportunities for development. What about talented youth from small towns?

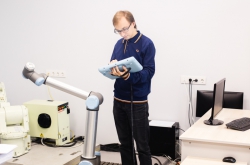

Ioffe Institute

Ioffe Institute

The council pays much attention to this problem. We contribute to the work of the Sirius center for talented children, organize youth forums, but that's still not enough. Also, there's the question of the real efficiency of measures we take for finding talents and supporting them. Lately, we've been working on the following idea: involving young scientists and Presidential Award winners in giving lectures about science in schools and universities. Yet, there are problems with it as well. First of all, it requires a lot of time. Also, giving lectures is an art of its own, one has to make them interesting and comprehensible. Still, the Council will definitely continue to work in that direction.

And, finally, please tell us about the new Master's program, Photonics of Dielectrics and Semiconductors that you'll be teaching.

This is a Master's program organized by the Department of Dielectric and Semiconductor Photonics as part of ITMO's collaboration with the Ioffe Institute. Most lectures will be given by those scientists from the Ioffe Institute who actively work in science. This is important, as students will get the opportunity to communicate with lecturers who know exactly what's relevant in a particular research field. We also want the students to participate in real projects in laboratories at least two days a week. This is a novelty: often, students don't have the time for serious practice. As of now, eight students who graduated from Bachelor's programs at the Polytechnical University, St. Petersburg State University and ITMO entered the program.