Digital philosophy and the reign of mathematics

Digital philosophy appeared as a discipline in the early ‘00s and kept getting more and more attention as technological revolution spread around the globe. The field is only beginning to develop in Russia and is currently most relevant in China and Japan. One of the most renowned researchers is Yuk Hui, a Chinese computer engineer, technology philosopher, and the author of On the Existence of Digital Objects.

Ever since Pythagoras claimed the numbers to be the core of everything else and therefore put mathematics before philosophy, these two disciplines were drifting apart. These days, however, we live in a reality where numbers do make up the essence of everything. Almost all of the information is transferred digitally, we are constantly interacting with programs and algorithms – be that chatting, digital payments or ticket bookings. And it will only get worse with the technological advance as the reality becomes more and more digitized (and humans just might join in).

Thus, digital philosophy studies information technology using mathematical equations as its primary method.

Digital philosophy uses the terms digital objects and data objects. Data objects are almost anything created online: music, pictures, texts – anything that can be viewed and decoded with a digital device (such as computers, smartphones or tablets). It might appear to be a rather complex array of data, but it all comes down to a combination of 1s and 0s, the code being its main essence.

Any data comprising a certain entity, such as a Facebook profile or an Instagram page, is called a digital object. They all exist and operate in the digital sphere. We would have called this sphere a virtual reality before, but nowadays this term is outdated and the very concept of virtuality is lost for good.

The philosophy of networks and networks as philosophy

The internet is in its core a network, an extremely complex system of connections between numerous devices and computers. It is comforting to think that it abides by certain rules and algorithms, that is has a logical inner structure, but it was true only at the very beginning of its existence. Nowadays, it is a free space with a chaotic structure, an enormous amount of intertwined information, which keeps multiplying.

The traditional methods seem to be unfit to study the internet – and that is where the so-called philosophy of networks comes in. The concept itself was coined long before the internet, but it does capture the processes happening inside it quite well. The appearance of this concept became the turning point for philosophy, as the concept of metaphysics reigned in the field before. Objects were believed to have a deeper reality, a certain absolute that, once reached, can reveal the answers to humanity’s most burning questions. The philosophy of networks deals not with the essence of objects, but with their interactions, while the reality is seen not as a sum of objects but as a network of connections and knots.

In the 1970s, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari came up with the concept of rhizome, which is best defined through the analogy with a mushroom spawn: it’s a non-hierarchical network that spreads not from the center, but from its knots and outer edges. The parts of a rhizome are equal, but the loss of one of them doesn’t bring with it the collapse of the whole system; a single part is insignificant. Doesn’t this look like a description of the internet?

Instagram for people and robots

One of the ways to analyse any social network is the actor-network theory created by Bruno Latour. It’s main maxim is in abolishing any existing preconceptions, thinking patterns or the inclination to simplify and reduce. No object can be boiled down to another one or simplified.

When we work with data objects, such as photos, we can’t say that they are simply photos, because there are many processes behind them. It’s the activity of the person who created it and uploaded it to the internet; it’s the program which encoded this object; it’s the device that can view this object.

The actor-network theory is separate from all the other methods, which tend to bring different phenomena down to only one level, be it social cultural, political or economic. This theory, on the contrary, allows us to create descriptions, comprised of several different entities.

The history and philosophy of the 20th century put humans at the core of any research activities, whereas now theoreticians tend to focus on other objects. The actor-network theory completely excludes humans. It is more interested in the way objects (or actors) interact with each other when left alone.

Instagram viewed through the lense of the actor-network theory stops being a human-like structure. When we look closer, we actually notice a number of its non-human factors.

To function properly, Instagram needs, first of all, a device (a computer or a smartphone, each with their different features. For instance, you can’t post pictures from a computer). Second, it needs the app itself. After that comes the content and only then do we reach the user.

The concept of an Instagram user itself is rather broad and not always human-like. A lot of accounts are owned by brands, companies or corporations, not to mention the growing number of bots. One of the most recent trends is digital influencers, essentially 3D models, which present themselves as actual people. Meanwhile the real people are pushed out of the digital world, substituted with algorithms, neural networks and programmed personalities.

Interdisciplinary research and big data

The internet is both a giant data archive and a black hole. We are caught in the endless process of creating data and drawn into the bottomless hole of navigating it.

Here, interdisciplinary research comes to our aid as we help each other to clear up this archive and make the massive data uploads look more concise, elegant and interesting. Sociologists and anthropologists set goals and tasks in their fields and big data specialists collect all the necessary information and help structure it.

It’s hard not to mention Lev Manovich, a new media theory specialist, when talking about big data. He is engaged in a brand new field of cultural research – using computer analysis and data-visualization to study cultural trends.

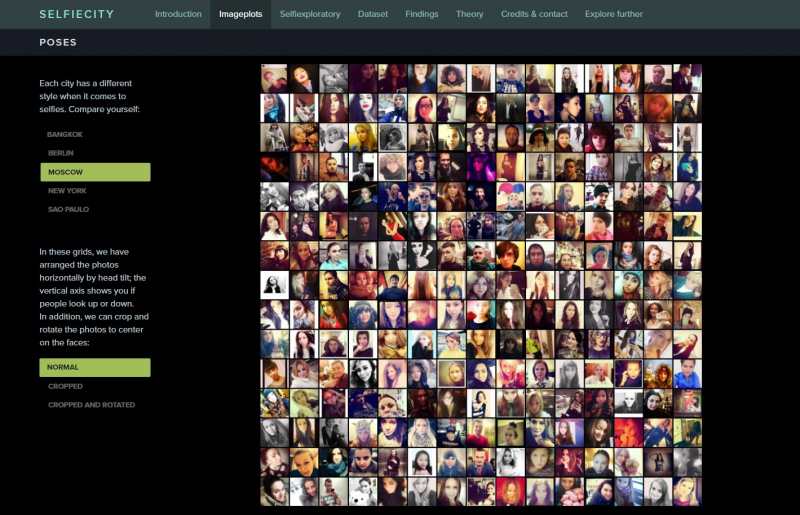

One of his lab’s most famous projects is the analysis of thousands of selfies from five different cities, which were uploaded to Instagram with a geotag. Judging by the number of smiling people (and the width of their smiles) the researchers were able to identify each city’s “positivity” level, as well as the men to women ratio, the age band and some less serious trends, such as the most popular selfie poses.

Why do we love data so much?

First of all, it’s objective. When a researcher tries to explain a certain question or problem, there is always a temptation to bring this explanation down to their own point of view. Numbers don’t let us distort the way we view the world. They are facts which only need to be interpreted within the framework of a certain discipline.

Second, data comes from different sources, it has different characteristics, which allows us to jump between different formats and levels in our analysis.

Third, the data is graphic by itself. We only need to find a form to present it, which is what media visualization is all about.

Data acquired from social networks can be applied in different fields. Marketing specialists use it to develop marketing strategies, urbanists consult them to create a better public utilities provision system while entrepreneurs can analyze it to establish their specialization and future audience. Meanwhile, sociologists and anthropologists address the modern society problems: the way new technologies transform the existing bonds (for example, those between parents and children), the principles of digital economy or the changing attitudes to work and labor.