Why do we do it?

A Google search reveals no official explanation for this particular detail of our curriculum. What I did manage to find, however, were the general benefits you get when memorizing and reciting something in front of a class – from new words and enunciacion skills to public speaking and battling stage fright. Naturally, as you grow older and the poems grow significantly more complex – in their rhymes, rhythms and the topics they delve in – you also start appreciating the intricacies of those metaphors and similes, the power a single word can have in changing the whole mood of a piece by revealing an unexpected detail.

Another clear benefit is a chance to polish and improve your memorization techniques. You won’t get anywhere without actually understanding the meaning behind the lines you need to recite. You need to find the structure within, and relate the meaning to your personal experiences, which are all crucial steps in learning literally any other bit of information ever, be that at school or university.

So, learning poems by heart and reciting them in front of a class equips us with a belief in the power of words, a chance to develop our public speaking skills and give us loads of practice material for active memorization (as opposed to rote learning). All in all, the idea behind it doesn’t seem so bad, though I won’t claim it always works flawlessly.

Lines from classical times

Any discussion of Russian literature can hardly avoid a mention of Alexander Pushkin in some form or another, as he is sometimes considered to be the founder of this very literature as we know and love today. Fun fact: he himself mostly spoke French in his early childhood (as many did back in the day) but then became a widely recognized young poet before graduating from the famous Imperial Lyceum still located near St. Petersburg in a town called Pushkin.

Some of his most recognizable lines, I’d say, come from Eugene Onegin, a verse-novel:

“My uncle's goodness is extreme,

If seriously he hath disease;

He hath acquired the world's esteem

And nothing more important sees;

A paragon of virtue he!

But what a nuisance it will be,

Chained to his bedside night and day

Without a chance to slip away. Ye need dissimulation base

A dying man with art to soothe,

Beneath his head the pillow smooth,

And physic bring with mournful face,

To sigh and meditate alone:

When will the devil take his own!"

A portrait of Alexander Pushkin (1827) by Orest Kiprensky. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

We also cannot do without what is sometimes called “Russia’s most famous love poem”, To*** Kern:

I keep in mind that magic moment:

When you appeared before my eyes

Like ghost, like fleeting apparition,

Like genius of the purest grace.

It seems almost a criminal offence to limit this mention to only two poems, but keeping with this brief review, I am hoping to provide something that will both let you in on our culture and interest you enough to learn more.

Having mentioned Pushkin, I have to give a nod to his contemporary, Mikhail Lermontov, who also did a lot of good for Russian literature both by his poems and his prose. His most famous work is an epic battle poem, Borodino. This is one of those works that literally every student has to learn in all its glory, so be sure that there’s probably no Russian who wouldn’t continue its starting lines:

Now tell me, Uncle, how'd it chance that

Our Moscow could be burnt to ashes

And captured by the French?

For up until the bitter end there

Were battles fierce and great in number,

And all of Russia still remembers

Borodino’s great clash!

A portrait of Mikhail Lermontov (1837) by Petr Zabolotskiy. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

One of my personal favorites at school was another great poet and diplomat, Fyodor Tyutchev. Many a verse could be mentioned here, some devoted to love and some focusing on nature, but there are four short lines that are bound to be known by anyone:

You will not grasp her with your mind

or cover with a common label,

for Russia is one of a kind —

believe in her, if you are able…

And, I guess, there is no need to explain their popularity. A treat for me at school was Nabokov’s translation of Silentium that I proudly recited together with the original version, so I would highly recommend you take a look at it, as it is definitely worth it.

Last century’s verses

We are moving on to the 20th century with so many names and lines ready to welcome us there, it’s almost impossible to choose but a few. If I really had to try, however, I would have to bring your attention to the following poets:

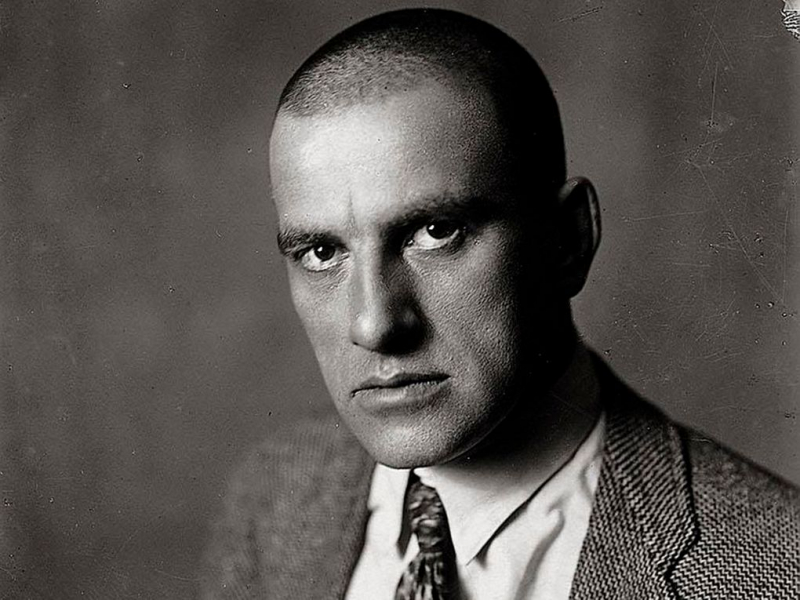

Vladimir Mayakovsky, with his declamatory writing style and unpredictable, graphic rhyming patterns. Though many of his lines are truly part of our daily speech at this point, I think no one will fail to recognize the origin of these words:

Now, listen!

Surely, If the stars are lit

there’s somebody who longs for them,

somebody who wants them to shine a bit,

somebody who calls it, that wee speck

of spittle, a gem?

A photograph of Vladimir Mayakovsky (circa 1920). Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

Sergei Yesenin, with his many love affairs resulting in lyrics that never once fail to touch the deepest corners of your soul, and his tender love for his motherland manifesting in his early verses. His Letter to Mother could be cited as one of his most known works:

Are you still alive, my dear old one?

I am still alive. My greetings to you!

May above your home that amazing light

shine on and dispel the evening gloom.

But, if I may, I would recommend you check out these two recordings of his Shagane you are my Shagane and The Fire Blazed Blue.

A portrait of Sergei Yesenin. Credit: Alex Northman / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0

Anna Akhmatova, whose creative genius made her work extremely diverse, including both short poems and longer cycles like Requiem uncovering the darkness of the Stalinist terror. Courage, however, a gravely resolute piece, is what I’d like to quote here today:

We know what is now on History’s scales,

What is, in the world, going now.

The hour of courage shew our clock’s hands.

Our courage will not bend its brow.

Her works have been extensively translated, but I believe it is important to say that not only her talent, but her fate, her perseverance and strength at the face of all of life’s troubles deserve to be known and looked into.

A portrait of Anna Akhmatova (1914) by Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaya. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

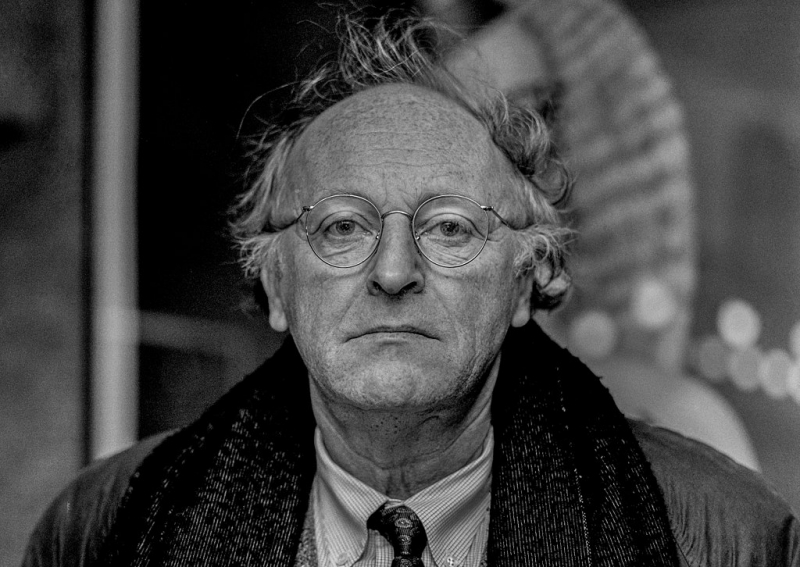

Finally, Joseph Brodsky, his lines gaining additional popularity now due to the highly topical:

Don’t leave the room, don’t make the mistake and run.

If you smoke Shipkas, why do you need Suns?

Things are silly out there, especially the happy clucks.

Just go to the john, and come right back.

A photograph of Joseph Brodsky (1995) by Sergey Bermeniev. Credit: Sergey Bermeniev / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0

These verses are likely to become the hymn of every self-isolating person. Apart from that, however, his works can also boast a wide variety of themes arranged, once again, in per times, unexpected rhymes and verses, always with a touch of metaphysics to them.

Undoubtedly, this is just the very tip of the poetic iceberg – and I am very conscious of that, but this crash course style introduction into the diverse and unique world of Russian poetry may be the path to many a wonderful discovery. We wish you good luck on your literary adventures!