First of all, let us congratulate you on your recent success at Web of Science Awards-2017, where you were recognized for contributions to science. You’ve had a great deal of success in the recent years, but you yourself have noted a 2012 study co-authored with scientists from ITMO University as one of your most important ones. Why is that?

I’d like to emphasize that the Web of Science Awards win is something that we won together with the researchers from ITMO University. I’m very happy to know that there are young, talented researchers with plenty of their own ideas and projects who are working today at ITMO’s International Research Center of Nanophotonics and Metamaterials.

As for research, I believe that we managed to pick the right topic. Before that, there was old, classic science, but we gave it a completely new twist.

How do you mean?

There is a science called nanophotonics that studies the physical processes that happen when photons interact with nanoscale objects. For a long time, nanophotonics was all about metals. How so? Well, because metals have a negative refraction index: if a wave hits metal, it is reflected entirely. Metal acts like a mirror, and the wave barely penetrates it. And nanophotonics is precisely about how light can be localized near the surface of metals and dielectrics and propagate in the form of surface plasmons.

But the issue is that metals heat up, which results in major energy loss. So we have this science, but it’s not very practical. Our team was among those who were the first to consider high-refraction index dielectrics. It turns out that if we create structures with Mie, or geometric, resonances, they will, too, localize light. That’s how this new field emerged. I recently came up with the name “metaoptics”, as it’s a more general term than metamaterials or metasurfaces. We use resonance to excite magnetic properties of non-magnetic materials.

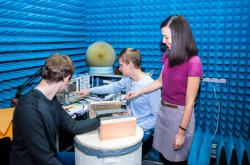

ITMO University began to study this new field intensely, as well as to find applications for it in other fields. Speaking of which, we’d recently discussed the possibility of collaborating on research with Ekaterina Skorb (Ekaterina Skorb is a professor at ITMO University and head of a research team at ITMO’s Biochemistry Cluster – Ed.)

What are the projects you’re working on right now? What issues in this field do you aim to solve?

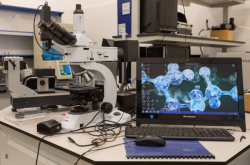

There are, undoubtedly, many tasks to complete in our field. For instance, we’ve just had a research project that we worked on with colleagues from Australia and Switzerland accepted into Science. It’s about biosensing. Kind of like a barcode, but with metasurfaces made out of resonators. Resonators are what we do.

There are also several projects we do here at ITMO University, some of them focusing on the topic of Mie resonance. It’s all quite dynamic. It took a while for nanophotonics to develop, but, since everyone was working with metals, there were very few practical applications and they weren’t quite effective. Dielectrics, on the other hand, can be used in every which way. And our team here is working hard on that topic.

What made it possible to go beyond metals?

For the longest time, people simply didn’t know what else they could do. Everyone was too used to doing what they’ve already been doing. Pavel Belov (Head of ITMO’s Faculty of Physics and Engineering and the International Research Center of Nanophotonics and Metamaterials – Ed.) and I had this problem: there was a very brilliant PhD student, Alexander Krasnok, who we just didn’t know where to apply. He started this area of study and found a place for himself; he’s working in Texas now.

Eight years ago you and Pavel Belov won a grant for the creation of a metamaterials lab at ITMO University. Today we have a full-fledged International Research Center of Nanophotonics and Metamaterials; the Faculty of Physics and Engineering has gone through a rehaul and several “mega-grants” have been won in recent years. What do you think caused all this rapid development?

I myself am really surprised at how fast things are changing at ITMO University. When I first came here in 2010, I was skeptical about everything and it wasn’t clear what’s going to happen next. But everything worked out. The university keeps on developing and it changes so much. It’s a totally different place today.

A lot of very talented scientists have joined the Center of Nanophotonics and Metamaterials, including those who have previously worked in Europe. We’ve created a point of attraction for new specialists here. For instance, we have a professor from the UK here; he could have gone anywhere, and he chose this place.

This department has some of the youngest staff in the university. You yourself had once been the youngest senior researcher at the Verkin Institute for Low-Temperature Physics and Engineering. What opportunities do young scientists have today in Russia and abroad?

I think there’s plenty of opportunities right now. You can work with co-authors from all over the world, study and work at international laboratories. We were just talking with a colleague earlier today about this. He said something like: “Well, we don’t have this particular device here; we can try to find one in Russia, but not everyone knows how to use it. But we’ve recently had these Italians visit us here, let’s send one of our staff there…”. All these connections that we’ve established let us use the capacities of the entire world, and, what is more, to work with our international colleagues as equals.

This is reminiscent of what was said at the Web of Science Awards by the head of Clarivate Analytics in Russia and CIS. He noted that “in recent years, positive trends in Russian science are becoming tendencies”. Do you notice these changes when you speak to your Russian colleagues?

Absolutely. Russian scientists used to be eager to be published anywhere, and now they’ve become “spoiled”: they only want to be published in the good places, somewhere they’ll be noticed and cited. And that’s a new level.

When I got the grant in 2010, I spoke to Pavel and asked him what sort of results he expected. He said: “Well if we could end up publishing an article or two in Physical Review Letters, that’d be great”. Today we don’t even think about Physical Review Letters. We’re aiming for Nature and Science. The past eight years have seen a massive breakthrough. Our philosophy has changed, and people strive to work on a different, higher level.

Last year marked another achievement: the journal Optics and Photonics News cited an article by ITMO University scientists as one of the most promising projects of 2017…

Alexey Slobozhanyuk was the lead author of that one. He got a PhD in Australia and was actually the first here to get a double degree: both a Russian one and one from abroad. These days, you have people lining up for double PhDs.

Programs like this help students expand their opportunities. And it’s great for them to be able to work both here and there. At the same time, they don’t need to move, yet they’ll still have an understanding of the wider world. Staying or going – that’s their decision, and it all comes down to personal preference.

You Hirsch index is one of the highest among physicists. People must ask you often how to become such a highly-cited researcher.

I was at a conference in Singapore last week where some young scientists from China asked me just that. My answer is simple: change your research topics. Throughout my career, I’ve already done that four times.

How do you choose?

When I got into solitons, I was with a very capable team, but it was also quite hard to do experiments. All our tasks were related to solid bodies, and it’s really hard to observe phonons, temperature, etc. in those conditions. At the same time, there appeared some optical tasks that were related in one way or another to solitons, and so I gradually moved towards optics. It was just more interesting; there was a lot of ways to learn through experimentation and not just theory. Others might prefer theory; it all depends on the person.

And how did you get into metamaterials?

This, too, was because of new work and new interests. I was then the editor of Physical Review E and went to many different conferences, including the APS March Meeting, which is held by the American Physical Society. It’s a prestigious event that attracts a lot of people.

While I was there, I stumbled upon my colleague Costas Soukoulis (Greek/American physicist, one of the world’s highly cited researchers according to Thompson Reuters – Ed.). We’d met a long time ago when he was trying to write to submit a scientific comment on an article of ours. We debated the matter and the comment was never published, and instead, we got to know each other.

Anyway, there we were, in a corridor at APS March Meeting. He says: “Come with me, Yuri, this might be interesting: some crazies are claiming that refraction index can be negative”. Soukoulis, mind you, is a pillar of modern physics. I went with him, checked it out; it was all really interesting, but confusing. I couldn’t tell if it was real or not.

I went back to Canberra, where I had this new PhD student, Ilya Shadrivov from Nizhny Novgorod. I asked him what he wanted to do. He says: “Well, solitons, of course, I’ve been studying them all my life”. “Listen here, – I say – you’re about to be the seventh person on the team who’s studying solitons. Don’t you want to do something else? Solve something new instead”. And so he did. We wrote an article that has now been cited more than 400 times. And that’s how we ended up researching a new field that no one had paid nearly any attention to before.

Yuri Kivshar was born in Kharkov. In 1989, at the age of 30, he became the youngest senior researcher at the famed Verkin Institute for Low-Temperature Physics and Engineering. After that, he worked at research centers in the USA, France, Spain, and Germany; in 1993, he accepted an invitation from the Australian Photonics Cooperative Research Centre. He is currently the head of Nonlinear Physics Centre at Australian National University. In 2010, Yuri Kivshar won a “mega-grant” for the creation of a metamaterials laboratory at ITMO University.