Everything for victory

The start of the Second World War changed the overall being of the Leningrad Institute of Fine Mechanics and Optics (LITMO), with some students and employees volunteered to the front, some prepared to evacuate to the Caucasus and then Cherepanovo (Novosibirsk Oblast), and others stayed in the besieged city to continue their work.

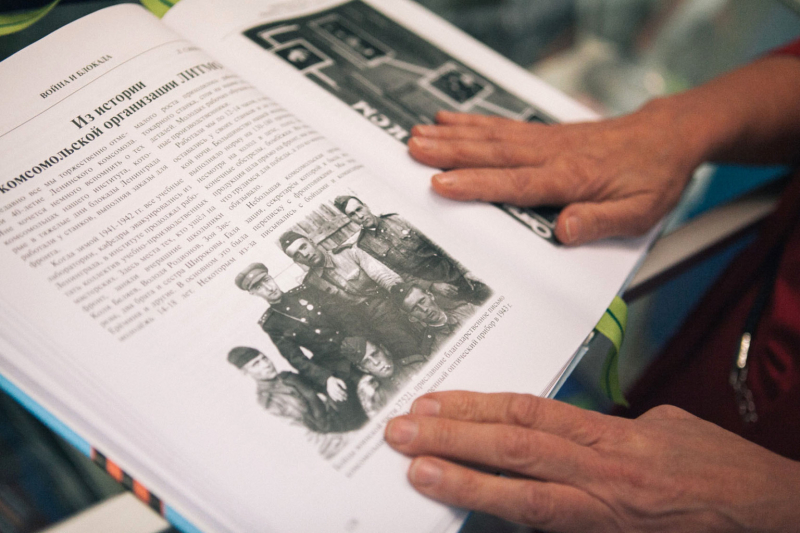

Following the initiative of the university’s head Sergei Shikanov and after approval of the city’s authorities, LITMO was transformed into a military maintenance workshop where the university’s students and staff built and repaired optical equipment during the wartime.

Thus, in the winter of 1941-1942, Semen Tsukkerman, a professor of LITMO, designed a novel towed anti-aircraft gun ЗП-1 in record several months, whereas any other time it would take up to 3-4 years to create such a device. In 1941, specialists produced a total of six sights for the second anti-aircraft rocket regiment of the Soviet Air Defence Forces that defended Smolny, including one for the Soviet cruiser Maxim Gorky, which participated in the defense of Leningrad.

Other developments of the workshop were a model of the clock mechanism for German aircraft bombs that was used to teach Soviet soldiers to disarm them, and a projectile's nozzle-end for the multiple rocket launcher БМ-13, better known as the Katyusha.

Read also:

Research Under Siege: How Leningrad Scientists Fought to Overcome Famine

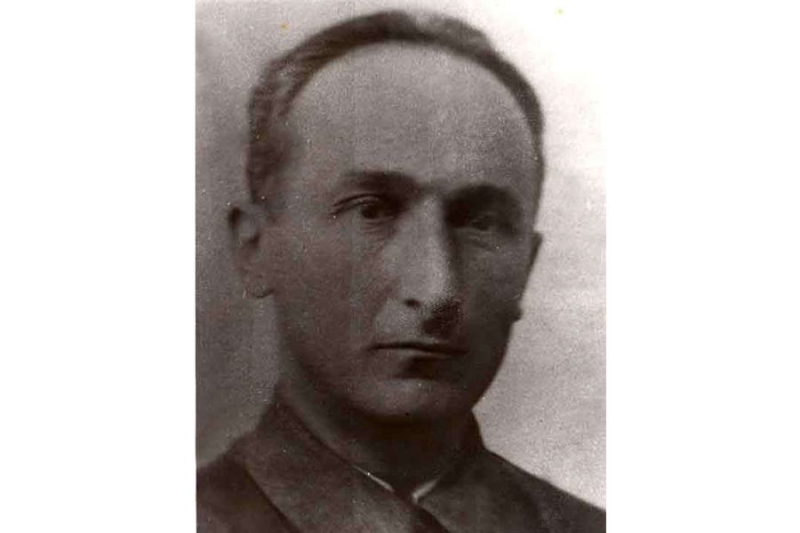

Head of the machining department, Vasily Egorov (right). Photo courtesy of ITMO’s Historical Museum

Engineering in the shelled city

The LITMO maintenance workshop welcomed many of the city’s families, including teens and even children. In 1942, the 16-year-old Vladimir Bogdanov joined the machine-assembly department, where he cleaned optics and repaired mechanical parts on a lathe. After the war, Vladimir became one of the renowned employees of the LITMO experimental factory. Many other family members of the institute staff contributed their efforts to the workshop.

The work went on even during the most brutal days of the Siege, when transport stopped, there was no water or electricity, and food supplies were at the bare minimum. At that time, mechanics used pedal drive equipment – with oil or battery lamps for light source. Operating turning and milling machines was even harder and required two people: one would spin the spindle to power the machine and the other would process the required mechanical component. Such pairs worked in 5-10-minute shifts – the work was too exhausting to do it any longer.

“We worked day and night, sometimes we even slept right beside our work stations – through bombings and shelling. Once, the university building was partly demolished by a bomb, but we powered on despite the danger in the remaining part of the workshop. Hunger, cold – no matter what, we continued working because the country needed good equipment and our team provided it. We were even nicknamed “the hardworking team” by one of the officials,” wrote Andrey Veselov, the head of the repair team.

A meeting at an engineering workshop at LITMO during the Siege of Leningrad. Left: lathe operator K. Korovkin, next to him is the head of the machining department, Vasily Egorov. Photo courtesy of ITMO’s Historical Museum

Because the workshop didn’t have a design department, the engineers had to assemble new tools and devices on their own and then test their inventions with their colleagues. This applied to all kinds of commissions, including complex binocular probes, commanders’ stereoscopic telescopes, and collimator sights. Some of the necessary parts were produced at the Kirov Factory, but many of those had to be processed by hand using chisels, hammers, and rasp files.

“Our most frequent commissions involved repairing binoculars, for which we didn’t have any special equipment. We were saved by the Pogarev’s family, who used the few hours of sleep the rest of us got at night to design a new collimator that could adjust binoculars of various constructions. This has significantly increased our productivity and, most importantly, the quality of our products,” wrote Andrey Veselov.

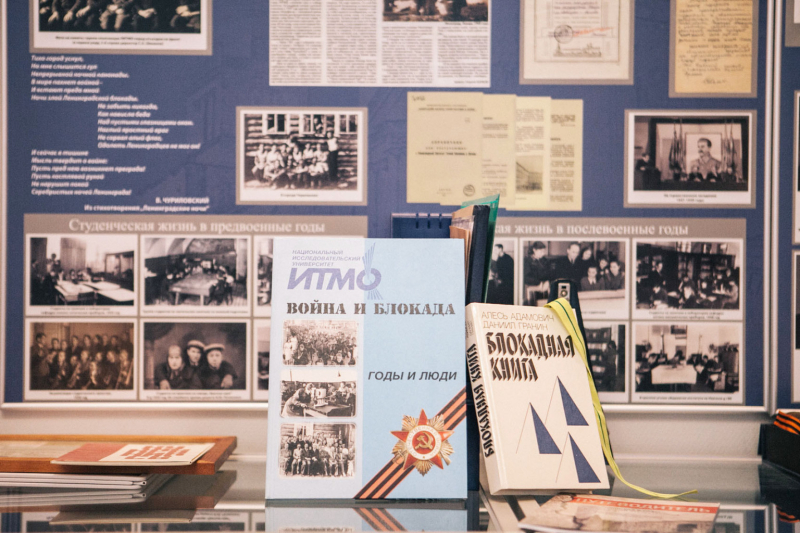

ITMO’s Historical Museum. Photo by ITMO.NEWS

In spite of any hardships, the workshop remained in operation even after the end of the Siege. Its employees contributed to the front by restoring damaged optical equipment and designing new devices, bringing closer the end of the war.