Making bread to feed a whole city

On September 8, 1941, the Axis powers, unable to take the city during their initial advance, began the Siege of Leningrad. The last – for the next 872 days – train bearing food products entered Leningrad on August 27, and on September 8 an enemy bombardment destroyed 3,000 tons of flour and 2,500 tons of sugar. At that time, Leningrad didn’t have enough food stored to feed its citizens: what was left could only last a month. The citizens were faced with a grave challenge: they needed to survive while cut off from the rest of the country.

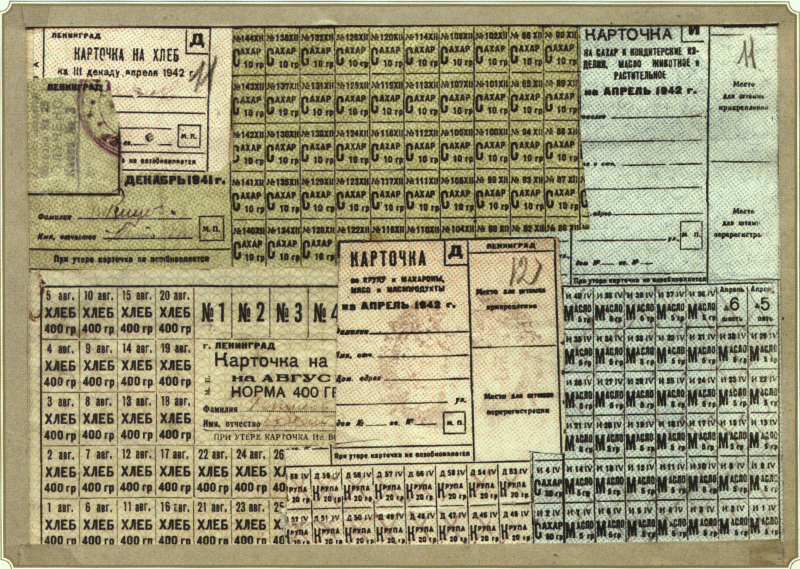

First, Leningrad’s bread factories produced bread from what ingredients remained in the city; however, the resources were running low, which meant the bread rations issued to each citizen were constantly decreasing as well. According to the regulation from November 20, 1941, factory workers and engineers received 250 grams of bread, while other categories of citizens, including children, had to do with only 125 grams. These were the lowest rations in the years of the siege.

Ration cards. Leningrad, 1942. Photo courtesy of ITMO’s Historical Museum

Anatoliy Zabelin, who headed an assembly room at a factory and was a lead engineer at LITMO (the Leningrad Institute of Fine Mechanics and Optics, the former name of ITMO University), wrote in his journal that it was impossible to get any food at a store and that it became common among citizens to wrestle bread out of each other’s hands. Hunger dominated the city.

At this time, the researchers who remained in besieged Leningrad were trying to find ways to develop substitutes for flour and other raw materials out of what little resources were left available. These efforts, led by biochemist Mikhail Knyaginichev, were carried out at a specialized lab of the Badaev bread factory, with contributions by engineer Pavel Plotnikov and microbiologist Zinaida Shmidt.

The researchers wanted to preserve the original product’s quality and nutritional value while also increasing its volume. Apart from the perils of bombing and regular power and water outages, the scientists had to overcome a severe shortage of resources. Because of that, over the years of the siege, among the “bread’s” components were dark rye flour, knotweed seed flour, saltbush, birchbark, flour dust, the pulp of various plants, soybean meal, and even hydrated cellulose. Moreover, Mikhail Knyaginichev came up with a special yeast culture that increased the product’s volume, saving the flour used per serving.

Over the years of the siege, over 26 tons of additives were used to produce an additional 50 tons of bread for the remaining citizens.

Read also:

How universities helped the city

As the siege began, the Leningrad Technological Institute of Refrigeration and the Leningrad Chemical and Technology Institute of Dairy Processing, which eventually became part of ITMO University in 2011, were requisitioned to conduct research and produce equipment to help feed the residents of Leningrad and soldiers on the front lines.

Scientists and engineers kept working even when there was no heat or power, risking death right in their workplaces. Over the years of the Siege of Leningrad, the Leningrad Technological Institute of Refrigeration alone lost over 100 people to starvation.

In spite of hunger and dire conditions, researchers managed to produce not one, but several developments meant to meet the needs of the besieged city and the front. Among those who succeeded was Ekaterina Danini, an associate professor at the Department of Chemistry, who together with fellow professors Semyon Parashchuk and Petr Romankov developed a production recipe for a soy milk made of by-products for children and wounded soldiers. Additionally, scientists established laboratories of chemical analysis and microbiology to monitor and control the quality of products.

Meanwhile, a team of the Department of Microbiology, led by associate professor Nikolay Novotelny, figured out how to ferment cellulose using fungi and use the materials obtained to, for instance, improve the quality of bread. Whereas the specialists of the Department of Food Production Equipment, associate professor Nikolay Golovkin and assistants Boris Novitsky and Vladimir Khizhnyakov, invented and designed a special-purpose dryer to quickly produce bread rusk for the frontline.

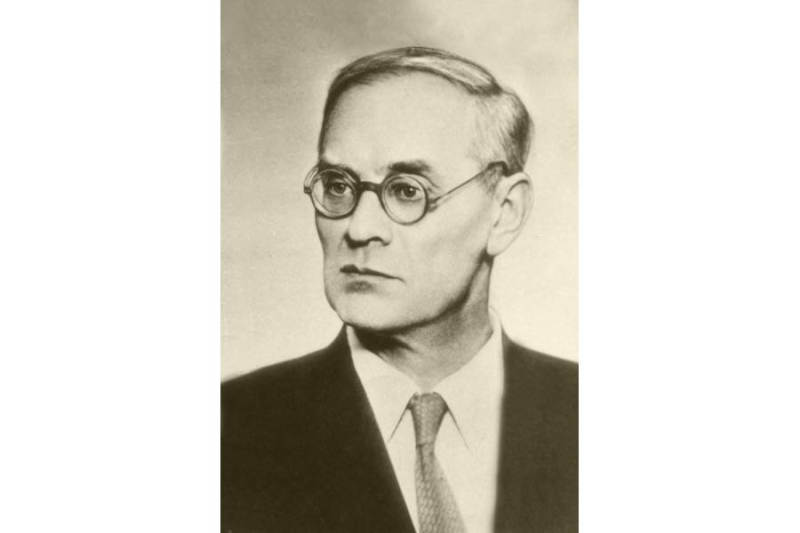

Nikolay Golovkin, the head of the Department of General and Refrigeration Food Production at the Leningrad Technological Institute of Refrigeration. Photo courtesy of ITMO’s Historical Museum

The Siege of Leningrad lasted 872 days. The first trains with food, raw materials, and ammunition arrived in Leningrad only in February 1943 as Soviet troops broke through the blockade. Nevertheless, the siege was not fully lifted for another year, until the launch of the Leningrad-Novgorod offensive in 1944.

Despite everything, Mikhail Knyaginichev survived. From 1960 to 1973, he, then-DSc, headed the Department of Organic, Physical, and Colloid Chemistry at the Leningrad Technological Institute of Refrigeration.