Behavioral economics describes the principles of decision making and shows the choices that we, as consumers, make in various circumstances. In economics, the concept of utility states that the more a product or service is beneficial to us, the more willing we are to pay for it. Daniel Kahneman, the 2002 Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences who founded the field of behavioral economics, proved in his experiments that we, as individual customers, almost never adhere to the utility function in our everyday decisions. The principles of basic economy cannot be applied to individual customers, and neither is the utility function. This discovery signified a major turn in late 20th – early 21st-century economics.

Problem #1

Say you’ve got a choice between opting for a guaranteed payout of $250 or a lottery where you have a 25% chance of winning $1,000 and a 75% of losing everything. Or how about one with losses: you may either lose $750, or have a go at a 75% chance of losing $1,000 to a 25% chance of losing nothing.

When you compare these situations, the mathematically correct strategy would seem to be the lottery option in the first case and the guaranteed loss in the second case. And yet, only 3% of all test subjects take the most rational decision during this experiment. What this tells us is that a majority of the population will knowingly choose the less beneficial option. And we have the framing effect to blame.

What is the framing effect?

The framing effect is one of the key phenomena in behavioral economics. When people do not have the full knowledge of a situation, they tend to make decisions differently than they would have if they had all the information available to them.

“The more we know, the better we make decisions. This seems fairly obvious, but people rarely apply that principle. We could blame classical education because we’re often taught to decompose our problems, i.e. take them apart into smaller subproblems – a principle that works well in science, but not so well in decision making. If you don’t consider the big picture, you’re likely to make the wrong decision,” explains Maxim Korotkov.

WYSIATI: why we don’t use our knowledge

The letters WYSIATI stand for “What You See Is All There Is”. When examining a problem, people tend not to apply their earlier-acquired knowledge to solve it. Attempting to remember something we already know can sometimes require an enormous amount of effort.

In a classic experiment on this topic, the subjects are asked to read a text describing an individual’s daily routine. The text contains references to the individual’s occupation and activities. Then, the readers are presented with a set of multiple choice questions and asked to pick the answers that best describe the character from the text. A classic American version of the questionnaire describes a “Linda who works in banking”. One of the questions has two answers: “Linda works in banking and is a Republican” and “Linda works in banking”. A majority of people tend to choose the first answer as they find her being a Republican bank employee more likely than simply being a bank employee, which is, of course, impossible. In most cases (over 60%), the average respondent simply doesn’t employ basic logic. That’s what we call WYSIATI: people take in information and make a decision based on that data, but don’t use logic.

Problem #2

If you offer someone a choice between a 61% chance of winning $5,200 and a 63% of winning $5,000, and then between a 98% chance of winning $5,200 and a 100% chance of winning $5,000, the majority of people would choose the 61% and 100% options. What does this tell us? People react differently to winning and losing. If you know that you have a large chance of winning a substantial sum, you start being more afraid of losing. In the first case, people are won over by the size of their prize, and in the second they cave in to the fear of ending up in the losing 2%.

“These are the economic effects which insurance companies rely on in their work. If you have even the slightest chance of losing a lot, you’ll be much more eager to give away a smaller sum for security. On the other hand, if it’s something like an extended several-years insurance on a washing machine, you’ll likely refuse it,” explains Maxim Korotkov.

50% isn’t always half

When we’re given a 98% probability, we evaluate the likelihood of ending up in the 2% and estimate it at around 9%. People are just incapable of applying small probabilities to themselves. If you’re told that the washing machine has a 1% failure rate in its third year of use, you’ll estimate it at 5.5% – and that’s what you’ll be ready to pay for.

Interestingly enough, 50% isn’t always perceived as a half, and tests show that people tend to undervalue wins.

Anchors

Early 21st-century studies posited that our behavior is affected by so-called anchors. Anchors are the experiments in which, for instance, a subject is shown an expressly random number and then asked how much something costs or how old Mahatma Gandhi was when he died. Such experiments showed that if the subject was shown, for instance, the number 60, then their subsequent answers would feature numbers close to that value. Plenty of literature has been written on exploiting this principle in negotiations, but scientific critics, including Daniel Kahneman, had proved that this principle almost never works. As soon as other factors come into play, or the subjects successfully recall the relevant information, the anchor is lost. Anchors, therefore, only work in artificial situations where people are only asked questions to which they do not know the answer.

Survivorship bias

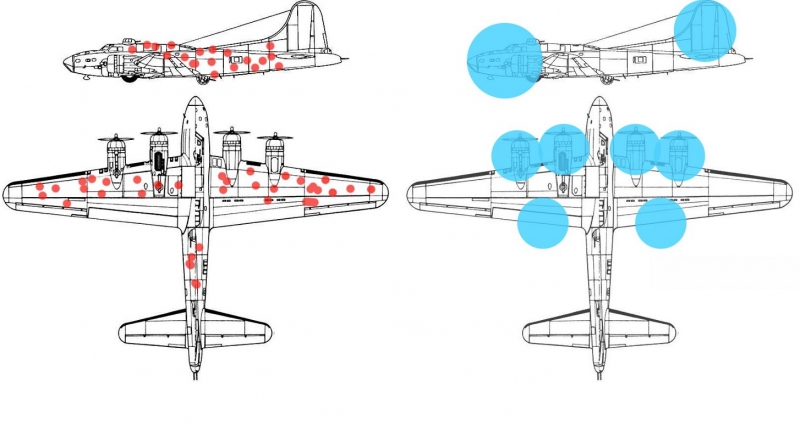

The concept of survivorship bias has existed long before behavioral economics, and it concerns the way we examine the results of experiments. Survivorship bias refers to the way we tend to pay attention to positive results of an experiment. A commonly cited example comes to us from World War II. Back then, engineers were tasked with identifying the areas on bomber planes’ fuselages that needed to be reinforced. Initially, additional armor was applied in areas which were most often shot up on airplanes returning from raids. But the error was that, instead, they should have reinforced the areas which were left untouched by enemy fire, as it meant that the planes that got hit there were unable to return to base.

The second part of survivorship bias is the disregard for the average. In education, teaching staff often praise those who did well on a particular task and berate those who didn’t. This is rarely the right approach, since intellectual labor involves not only knowledge but also a bit of luck. A better approach would be to monitor the students’ overall performance and point out ones who are failing or improving.

Intuition vs Math

System 1 makes decisions intuitively. In all experiments where unimportant decisions have to be made quickly, system 1 is at work. In fact, we use it for the most part of our life. System 2 is the rational brain which we don’t use as often. It may prove difficult to shift the controls to system 2, as our human brain, trained over millennia, believes that decisions must be simple and quick. Intuition, however, fails us in problems that concern economic benefit. And that’s why even the simplest mathematical model is better than a gut feeling.