A more realistic perspective on science

Andrei, can you start by telling us a bit about what STS is?

STS stands for Science and Technology Studies. For the longest time, philosophical approaches reigned over this field and formed an idealized and therefore unrealistic image of science.

How long has this field existed?

Compared to other social sciences, STS is rather young. It emerged in the 70’s in the UK, France, and the Netherlands. It was then that a number of breakthrough studies were conducted that have greatly affected how we perceive science today. It quickly developed and spread into the United States and Northern Europe. STS came to Russia in the late 00’s and now we’ve finally launched one of the nation’s first Master’s programs in that field.

What does STS research look like?

Since its inception, STS has been an interdisciplinary field composed of specialists in social, political, and historical sciences, anthropology, and philosophy. Research was done in different fields. I’ll just give you two examples. On the one hand, a crucial part was the study of scientific disputes. Researchers study the dynamics of scientific knowledge not after the disputes are done – when it’s clear who’s right and who’s wrong – but before that.

Analyzing the actual process of debate also made it possible to understand how scientists come to a consensus. The main takeaway was that scientists, like every other social group, use not only logical arguments, but also all the cultural resources available to them. On the other hand, anthropological studies of laboratories have, too, become a classic element of STS.

For instance, the French sociologist Bruno Latour spent two years studying a neuroendocrine research lab at the Salk Institute in San Diego, California while working there as a technician. Based on what he saw there, he co-wrote the book Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts with the British sociologist Steve Woolgar, in which they describe the writing processes of research papers, the history of the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone, the microprocesses of how data is interpreted by scientists, and much more.

What happened next?

Researchers had to change the idea of how the general public participates in creating scientific knowledge, as well as how science changes society. Latour wrote a book about Louis Pasteur which resonates very much with the current situation concerning COVID-19. He demonstrated how today’s high-population-density cities would never have existed if not for Pasteur’s practices of discovering and fighting microorganisms, which were then adopted by a multitude of public institutions. In English, the book was published under the laconic name The Pasteurization of France. On the one hand, the current pandemic shows us how dangerous it was to live in large communities in Pasteur’s times; on the other hand, it shows that scientific knowledge and social relations are closely interwoven.

STS specialist – the profession of the future

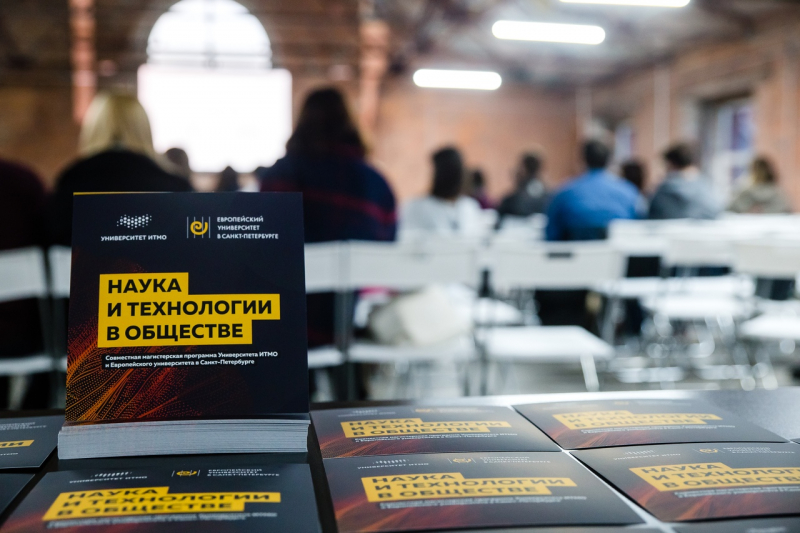

What is it that students learn in the Science and Technologies in Society Master’s program?

They learn to see science and technology in a new light. Scientists and engineers maintain a rather persistent discourse on what it is they do. These stories bear an ideological character, and they make it difficult to get to the truth. We ask students to pay attention not to what researchers say, but to what they do. To do that, you need to adopt a certain point of view, to pick the right moment to start, to treat information critically and not to accept at face value everything said by scientists, engineers, and innovators about their own work – while also not denying the value of their work.

But we also teach them to see the connection between technologies and social processes such as political relations, customer experiences, investor interests, and so on.

To what fields does this knowledge contribute?

To many. In the 80’s, STS began to concern itself with technologies. Today, we use STS methods to study cities, art, laws, politics, economy – pretty much all the important aspects of our lives. Some of the more pressing issues for us are those of the close interdependence of scientific and political disputes, such as what you can see with climate change or, once again, COVID-19.

Besides continuing their careers in research, what can the students of the program go on to do?

The labor market for STS specialists is still forming. But even today, they are already in demand among science management departments. Our graduates will know what really drives science and therefore be able to shape scientific and innovation policies. Their ability to understand connections between science, technologies, and society will make it possible to create more effective high tech initiatives and products. And that’s valuable not only to state institutions, but to tech companies, too. They can calculate the risks related to the adoption of innovations and analyze their chances of success, which is a valuable skill in the commercial sector.

Are the students able to practice on real commercial cases?

Our program is only in its first year, so we’re just starting to establish connections with research groups and tech companies. But even today, we’re already teaching our students to study real cases and the factors that affect scientific and technological development in real life.

What makes specialists of this kind important to society?

Social relations are becoming increasingly connected to technology and science. It’s impossible to understand today’s society without understanding modern science and technology – and vice versa. Specialists who can do that are, undoubtedly, the professionals of tomorrow. And we’re training them today.