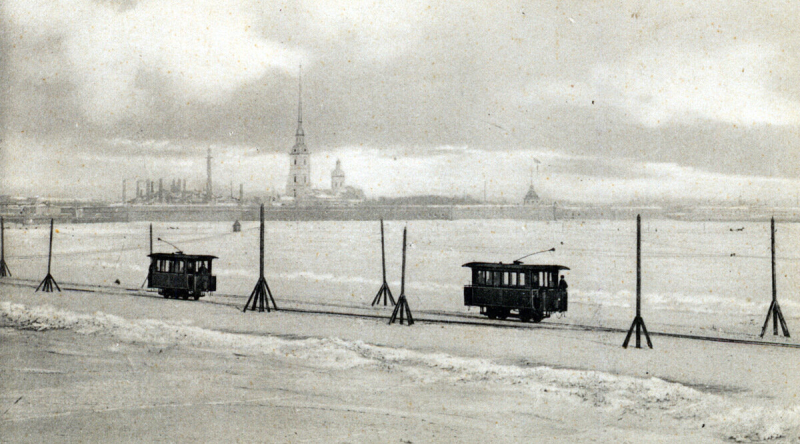

Ice tram

If you think that this year’s winter in St. Petersburg is vicious, think again. For a 15-year stretch at the turn of the 20th century, winters in the city were strong enough to support not one, not two, but four tram lines running on the frozen surface of the river Neva!

The slightly surreal set-up was the result of a legal loophole – at the time, the horse-tram association had a monopoly on the operation of public transport lines “on the streets of St. Petersburg,” but no such rule applied to the river. Thus, the city’s steamboat association made smart use of sturdy ice and horse-trams converted into electric transport. Each tram ran at 20 km/h and could carry up to 20 passengers. The lines, which operated from January to March, criss-crossed the river at several places in the city center; the westernmost ran from Senate Square to the Academy of Arts, and the easternmost – from Suvorov Square to the Vyborg Side.

Ice house

Wedding at the Ice House (1878) by Valery Jacobi. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

Another miracle of wintertime engineering in Imperial-era St. Petersburg was the iconic Ice House. During a particularly harsh winter in 1739-1740, the Empress Anna Ivanovna, who was infamous for funding extravagant projects and spectacles, decided to mark the country’s victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735-1739 by building an entire “palace” out of ice right on the surface of the Neva.

Inside the Ice House were multiple rooms, including even a toilet, and furnishings carved out of ice. Throughout that winter, it hosted several balls and, finally, a mock wedding for the empress’ court jester. The edifice, which was closer in size to a medium-size mansion, was so sturdy that bits of it reportedly remained intact all the way into June of 1740.

Nyenshantz

A model of the Nyenschantz Fortress. Credit: Evgeny Gerashchenko / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.5

We’ll concede, this one might be slightly cheating – after all, it predates St. Petersburg by some decades – but it’s a far too fascinating subject not to touch upon. Guests of the city are often unaware that St. Petersburg wasn’t actually the first city to be founded on the banks of the Neva Delta.

Nearly a century before Peter the Great broke ground of Russia’s new capital, the Swedish city of Nyen was established on the nearby Okhta river, along with a fortress named Nyenschantz. A prominent trading hub, it was eventually surrendered to Russia during the Great Northern War and was eventually abandoned in favor of a new castle – the now-iconic Peter and Paul Fortress. Nowadays, aside from a memorial plaque, few signs remain of that historical curio, although archaeologists were successful in uncovering some parts of the star-shaped fort.

St. Michael’s Castle

Mikhailovsky (St. Michael's) Castle. Credit: Godot13 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

Call it dramatic irony or a self-fulfilling prophecy, but the fact remains: St. Michael’s Castle had one job – and it failed spectacularly. Also known as the Engineers’ Castle, it was built in 1797-1801 for the Emperor Paul I, who was famously (and justifiably) paranoid about an attempt on his life. Believing the Winter Palace to be an unsafe place for himself, Paul ordered his architects to construct an imposing castle-like palace, complete with a moat and drawbridges.

Tragically, the ruler only got to spend a little over a month at his “panic room” residence. After just 40 nights, he was killed in his bedroom during a military coup. The imperial residence was swiftly moved back to the Winter Palace, while St. Michael’s remained uninhabited for a further 22 years. Even today, it holds a reputation as perhaps St. Petersburg’s most haunted landmark.

For more Russian history insights, check out our features on cool and obscure inventions from Russian history, the five Russian words with unexpected origins, and the Soviet slang that lives on.