The era of Peter the Great’s reign was characterized by the attempted Europeanization of Russia: this included changes in lifestyle, art, architecture, politics, etc. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that this process also led to the increased flow of international visitors – not only diplomats and traders but also artists, architects, cooks, gardeners, and so on.

Among other things, they were attracted by a manifesto issued by Peter the Great on April 16, 1702. It promised that foreign specialists would be able to travel to Russia freely, as well as enjoy religious freedom and lenient laws. Moreover, they were also typically paid more than the locals. Even though in the years to come more regulations followed, the number of international workers increased significantly.

Given that, for the most part, those were educated and highly literate people and Russia was something exotic for them, they often took notes on their impressions of the country and its inhabitants. This allows us to take a look at Russia from a different point of view and see what surprised the Europeans of the past.

Adam Olearius (1599-1671)

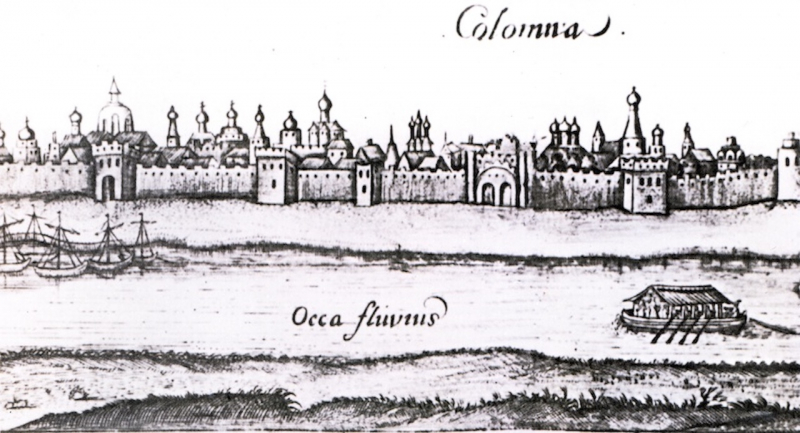

When it comes to the 17th century, one of the most elaborate descriptions of Russia was left by Adam Olearius, a scientist and a traveler who visited the country four times and published a book (Description of Travels in Muscovy, Tartary and Persia) – with lots of illustrations done by him, as well – about this experience. Let’s check out some of the things that shocked or amused him:

-

Buildings in Moscow were mostly made of wood, which caused lots of fires. Stone houses were a prerogative of rich people. The roads were wooden, too, and got extremely muddy, especially in autumn.

-

You could travel on sleigh rather comfortably, even in frosty weather: soft and warm blankets or coats allowed you to keep warm – sometimes even too warm – while riding. Travelers could also take a nap, as the horses were naturally controlled by peasants.

-

Even though local women were beautiful, the ones living in the cities used too much makeup (white powder and rouge), which made them look too unnatural and ridiculous. Some of them also painted their brows and eyelashes black or brown.

-

On wealthy women’s activities, Adam Oleandrius wrote that they rarely left their houses, especially alone – without a husband, a brother, or a father – and when they did, it was only to visit a church or someone they knew.

-

People used to swear. A lot and too much. Even children used nasty words that he wouldn’t dare to repeat.

-

Food was really cheap compared to European prices.

-

When it comes to health-related issues, Russian people were quite strong – in case of fever, all medication they needed was basically vodka and garlic.

-

New Year was celebrated in autumn, on September 1 (This was changed by Peter the Great in 1699 – Ed.).

-

Banya (or sauna) wasn’t a widespread phenomenon in Europe, so the German traveler was surprised by that as well: men and women could visit it together and then go outside to cool down, all while absolutely naked.

-

Moscow wasn’t very safe: you could get robbed easily if you didn’t have a gun or company, especially at night.

Other authors

Foy de la Neuville, a diplomat from France, wrote a controversial account on 17th-century Russia in which he mentions that in Moscow, people don’t eat and drink well – all they have are cucumbers and watermelons from Astrakhan, as well as flour and salt.

A member of the Swedish diplomatic campaign to Moscow, Johan Philip Kilburger, who left a description of Russia in 1679, was in his turn impressed by kvass: he described it as a drink made of water and malt that is kept in an open bowl. In the evening, it would be filled with the same amount of water as had been drunk during the day; in the morning, the bowl would be full of kvass again.

Paul of Aleppo (1627–1669), the archdeacon of Aleppo, was amazed by Russian architecture, especially the Moscow Kremlin – he wrote that nowhere else had he seen fortified walls with downward-facing windows, which allowed its defenders to shoot enemies who got close to the Kremlin’s wall. He was also surprised by the nearby floating wooden bridge: maids and peasants came there to wash clothes because its construction meant it was always close to the water surface.