Ekaterina Aleksandrova is the head of a study on health and life quality as part of ITMO’s Well-Being strategic project. The research team plans to collect data and evaluate the well-being of students and employees, as well as offer ways to improve physical and mental health indicators within the academic environment. Research is expected to last several years. The creators plan to scale it up and continue the study at other universities. Ekaterina Alexandrova discussed the project and its expected results with ITMO.NEWS.

What is health economics?

Health economics is an interdisciplinary term at the intersection of public health, behavioral sociology, and epidemiology. It shouldn’t be confused with healthcare economics because these are different things.

One of the main tasks of this field is to determine how to measure health from an economic point of view. Demographers believe that this is easy – there are indicators of mortality, fertility, and life expectancy. But if we follow the basic and most commonly used definition of health, which is given by WHO, we’ll see that “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This definition should be kept in mind when you’re choosing a tool for health evaluation. Economists look at everything as a resource and human resources are no exception. Therefore, for them, the most important indicator is what state of health of an individual will bring the maximum benefit to society. Simply put, they need to know when a person is healthy enough to create the marginal product of labor for society.

Generally speaking, a person should be healthy, educated, productive, and so on. What we’re trying to do is measure the effectiveness of this or that state of an individual’s health in terms of social preferences and considering that social resources are limited. Such evaluation helps set priorities in the healthcare system and identify the differences between distinct groups within the population.

Results of such studies allow us to compare the amount of money spent on a health protection program and the benefit it brought – say, an increased life expectancy or improved well-being. In a way, health can be measured by financial indicators – that’s what health economics is for. For example, a doctor must choose a medication: either a cheap and efficient drug, or a pill that will cure the patient but is worth one million rubles. What should they do? We realize that financial resources are limited and the choice depends on how a person and society overall evaluate the benefit of becoming healthy as compared to its costs. This isn’t an easy task but economists have learned to manage this issue.

How do they do it?

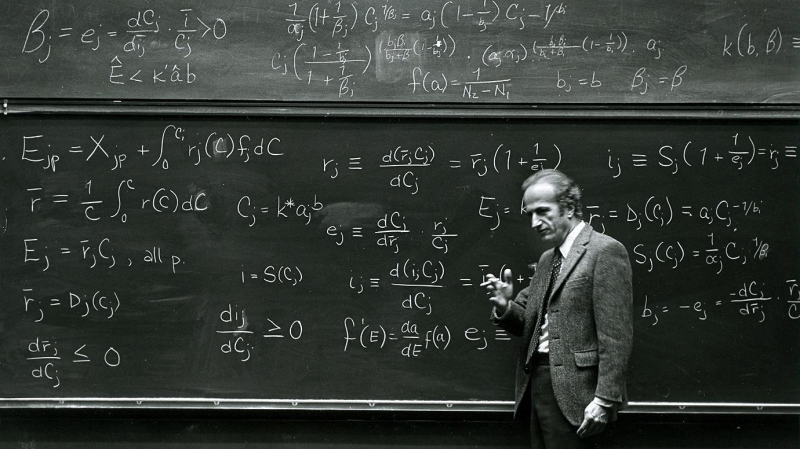

First, there was Gary Becker’s theory of human capital, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Based on this theory, economists justified the transition to a new education system and estimated each added year of education in terms of financial costs of an individual, the state, and households. Becker's student, Michael Grossman, applied these principles to the healthcare industry and in 1972 created the model of health demand. This was a breakthrough and his research lies at the foundation of a brand-new field, health economics. That’s when research aimed at answering questions like “How to measure health?” and “What affects health capital?” began.

At the same time, health is a rather complex characteristic. On the one hand, it largely determines our ability to learn, work, and develop. On the other hand, there are many factors that influence health and it’s quite difficult to take them all into account.

Gary Becker. Credit: The University of Chicago, news.uchicago.edu

Can you give us another example?

A classic example discovered by Beckker and Grossman is the correlation between education and health (educated people tend to be healthier). But such studies are valuable only to a certain extent, as they pose new questions: Does this mean that we should make everyone study for 20 years so that they would be healthy? Why exactly are these factors related? Maybe because people with a good education have a higher income, or maybe they were healthier initially and that’s why they were able to overcome all the obstacles associated with studying.

We’re interested in research of how the process of learning influences mental health. Does this process have a negative impact on our lifestyle? Sometimes students try to compensate for stress by, for example, using psychoactive substances and alcohol. We tend to think it’s about their age but in fact this can be a reaction to the stress of studying.

Then we can take a step forward and try to determine what the education system can do to prevent students from smoking and stimulate them to eat healthy food and do sports. This can only be achieved through field research, focus groups, surveys, and, most importantly, experiments in the form of interventions. However, we must develop research designs, evaluate costs, take measurements, and evaluate the efficiency of this or that intervention. It’s not just about banning smoking outside the university – such measures are unlikely to have any positive effects on the health of students and staff.

What kind of interventions could be used instead?

For example, in our project at ITMO, we plan to hold consultations with doctors and psychologists – we already have an agreement with a private clinic that is ready to provide us with specialists to carry out such an intervention. We can also send messages or push notifications to motivate participants to stick to a healthy lifestyle. There’s also an idea for focus groups – we want to first ask the participants what they think about, say, the effects of smoking, tell them about the consequences of an unhealthy lifestyle, let them consult psychologists and doctors – and then see if their attitude to smoking changes. In general, these are all fairly common methods and examples from the scientific literature. Similar experiments have been carried out that have proven to be effective.

At the same time, we should know that some interventions are useless: for example, it might be insufficient to hand out swimming pool or gym vouchers. Such situations might feel like a failure but it’s possible to understand why this happens – that’s what qualitative analysis methods are for. Perhaps, students who received vouchers weren’t planning on investing in their health. So it would be good to hold a preliminary consultation with a specialist who would explain what a healthy lifestyle is and what it involves.

On the other hand, it might turn out that there are many students who would like to care about their health more but don’t have enough money – in this case, vouchers would be an efficient solution. So it’s important to evaluate the number of motivated people who want to make some improvements before we start implementing a policy.

What do you plan to do as part of your research at ITMO?

We would like to emphasize that this is a pilot study – firstly, we want to understand how valid our evaluation tools are for the academic environment. For example, how applicable our questionnaires are. Surely it’s stressful to study at a technical university, but how exactly are we going to evaluate the mental health of our students? After all, you need to take into account a whole range of indicators, including depression, anxiety, stress, and so on. We need very personalized questions for self-assessment, because the concept of health is very subjective.

Project team of the International Center for Health Economics, Management, and Policy and ITMO's Center for Science Communication. Credit: Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS.

Of course, we’ll also measure objective indicators: body mass index, blood pressure, pulse, cholesterol and hemoglobin levels. These are basic indicators that help identify health problems. There’ll also be a questionnaire that will make it possible to identify those people who are predisposed to certain socially significant diseases and identify risk groups.

Right now we’re in the middle of developing the research design. We need to realize how to attract people and how to keep them interested in long-term cooperation. We must explain why it’s worthy and beneficial for them, the university, science, and society. Participation in research and experiments isn’t a popular activity in Russia so we hope to find a way to attract people.

If we manage to present the information in the right way, I hope our experiment will succeed. This study will help us answer lots of questions related to tools, health, risk groups, and the organization of information and knowledge on the project. Then we’ll be able to recommend our methods to other universities and organizations.

Do any other universities conduct such research?

I know that a mental health survey was conducted at Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology at the end of last year and many risky trends were identified thanks to it. Surely there are similar surveys at many universities – people begin to value such research more. What makes our project different is that, firstly, we work out the design of each stage in a qualitative and detailed way, explaining what we’re doing and why. We use reliable and valid tools to get trustworthy results. Secondly, we plan a cohort study, which will collect not only self-assessments of respondents' health indicators, but also objective indicators – blood tests and physical measurements. Thirdly, since this is a comprehensive study, we’ll not only identify problems but will also suggest evidence-based practices and interventions to solve them.

How many participants do you expect to have?

We plan to invite all students and employees of ITMO University to participate. Usually in such cases, about 20-25% of people agree. We hope for at least 300 volunteers who’ll make it at least up to the stage where we’ll take measurements and samples. A smaller number wouldn’t be representative and we won’t be able to form control and experimental groups. But I think it’s quite achievable. We already have experience in this area and people tend to gladly agree to participate in research when it comes to health, as everyone cares about it.

Ideally, we need a group for a cohort study – these participants will be checked on and surveyed every year. But we know the risks: some people might change their workplace, graduate, or simply refuse to participate, so for now we only plan this project for a year, as a pilot study, but we’d like to examine this group for a longer time.

What’s next?

If we succeed, we’ll have efficient and tested tools to be applied in public health by the Russian academic community. Our mission is to develop suitable practices, policies, as well as tools for the evaluation of programs aimed at health protection and improvement.