Science + art = insight

Science and art are more deeply intertwined than might seem from the first glance. For instance, the features that have made some paintings truly famous are rooted in chemical knowledge. Recently, researchers from the University of Amsterdam and the Rijksmuseum have found that Rembrandt’s celebrated painting The Night Watch owes its glowing look to special pigments made from a wide range of substances: the yellow paint is based on lead and tin, while the red-orange was produced with arsenic and sulfur. According to researchers, Rembrandt may have intentionally combined these toxic elements with pigments to produce the needed golden hue.

The Night Watch (1642) by Rembrandt van Rijn. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

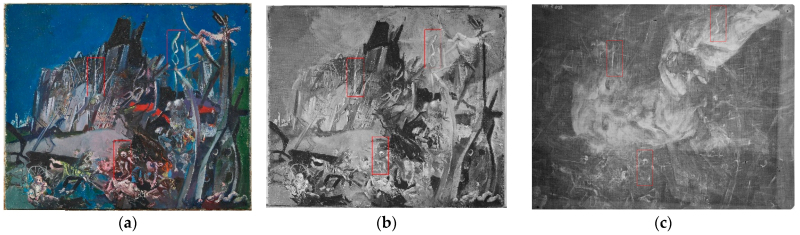

In addition, scientific methods can confirm the authenticity of artistic works as well as restore ones that are seemingly lost. Last year, scientists from ITMO discovered a previously unknown work by the prominent German artist Werner Tübke under the top layer of his painting Hiroshima I. The artwork was analyzed at a laboratory of the Russian Museum using non-destructive optical methods. The most significant results were obtained via infrared reflectography and radiography.

With the help of infrared reflectography, the scientists discovered inconsistencies between the visible image (a) and, below it, a vague silhouette on a lower layer of paint and detectable in the infrared spectrum (b). Then, they performed an X-ray scan of the painting to uncover a male portrait (c). Images courtesy of the research team

“Science can tell us how art is made. Scientists can tell us why, from a technical point of view, a particular painting has a particular effect on the viewer – or why it has undergone certain changes since it was made. It is such technological studies of paint ingredients, storage conditions, and the ‘decay’ of various materials that allow us to peek into the artist’s ‘kitchen’ of sorts. And this information can change our perception of art,” says Anna Peycheva, an art historian and head of youth activities at the Russian Center for Museum Pedagogics and Creative Initiatives (a part of the State Russian Museum).

Secrets of the old masters

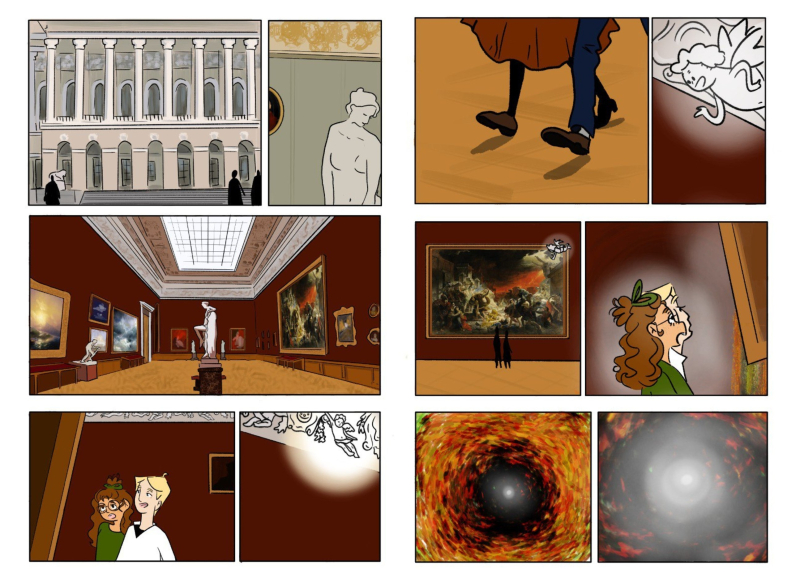

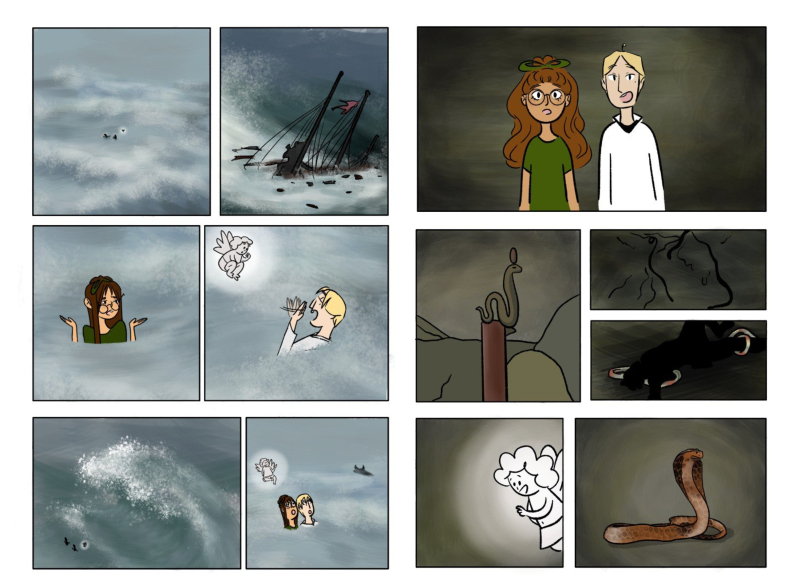

Within the project Masterpieces Through Scientists’ Eyes, co-organized by ITMO’s Center for Science Communication and the State Russian Museum, the authors shine a new light on three iconic paintings: The Last Day of Pompeii by Karl Bryullov, Wave by Ivan Aivazovsky, and The Brazen Serpent by Fyodor Bruni. All three of these works are united by a shared motif of “humanity versus forces of nature” and can thus be examined as an ensemble.

The paintings were analyzed by ten scientists. The Last Day of Pompeii was examined by: Alexey Ozerov, a volcanologist and corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS); Danila Chebrov, a seismologist and PhD in physics and mathematics; and Yulli Uletova, a scholar of the history of Pompeii.

Wave was the subject of focus for Alexander Osadchiev, an oceanologist and PhD in physics and mathematics; Svetlana Ulasevich, an associate professor at ITMO’s Infochemistry Scientific Center; and Maxim Volynsky, a PhD in technical sciences and the head of ITMO’s Scientific and Educational Laboratory “Machine Vision.”

Wave (1889) by Ivan Aivazovsky. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

The Brazen Serpent was analyzed by Irina Timofeeva, an ecologist and expert in biodiversity; Dmitry Chechin, a meteorologist, PhD in physics and mathematics, and senior researcher at the Obukhov Institute of Atmospheric Physics; and Ekaterina Kolycheva, an anthropologist and religious studies scholar.

The project’s authors also sourced general commentary on all three paintings from Natalya Kiselnikova, PhD in psychological sciences and the head of Psychodemia, a scientific laboratory of consultative psychology and psychotherapy. All of the involved experts represented various scientific fields that, in one way or another, study natural phenomena. This approach allowed the team to produce a comprehensive overview of the artworks.

“Scientists compare our world with that imagined by the artists, but seek to find parallels rather than conflicts. The data obtained from researchers and art historians is mutually complementary and allows both sides to see details they hadn’t noticed before. For the scientists, this was an atypical research task that placed them in an unusual context,” says Olga Remneva, the project’s curator, an art historian, science art expert, and lecturer within the Master’s program Art & Science at ITMO.

The Last Day of Pompeii (1830-1833) by Karl Bryullov. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

For instance, volcanologists have previously dispelled the myth that all of the subjects of Bryullov’s painting would have died in an avalanche of lava. In fact, most Pompeiians perished in a cloud of ash long before the city was buried by volcanic material. Meanwhile, chemical analysis has shown that the unusual color of the waves on Aivazovsky’s painting may be a result of the work of deep-water bacteria. Another possible explanation lies with the temperature changes that occur during a storm.

“A climatologist confirmed to us that the unusual premise of The Brazen Serpent could indeed occur. Scientists are aware of several accounts of animal ‘precipitation.’ Most often, such rain consists of fish, frogs, or toads. And though snakes aren’t at the top of that list, it’s impossible to deny the possibility of such a phenomenon. The possible causes are hurricanes and tornadoes. Small – and even large – creatures end up in the air due to the low pressure within the vortex, the strong updrafts, and the high speed of the wind,” says Arina Uskova, an ITMO graduate who was the project’s scientific collaboration manager.

The Brazen Serpent (1841) by Fyodor Bruni. Credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain image)

Where to see it for yourself

The findings of the project have been explained in more detail in a comic book (link in Russian). This format is suitable for children and adults alike. In addition, according to its author, Aleksandra Dushkina, a graduate of the Master’s program Science Communication at ITMO, it made it possible to organically embed the artistic masterpieces into a modern work of literature. A physical version of the comic can be acquired for free by visitors of the Russian Museum at the entrance to the exhibition Karl the Great, which is dedicated to the 225th birth anniversary of the great artist. The exhibition will run until May 12, 2025.

Even more insights are available in a special longform article (link in Russian) written by the project’s authors with the science journalist and ITMO lecturer Maria Pazi. In the text, the paintings are analyzed in further detail and accompanied by special commentary from the scientists.

This latest project is just one way in which the general public get to experience familiar subjects from a new perspective. Just this year, the Center for Science Communication has also conducted lectures, quests, tours of the city, and pop-sci quizzes. All these events were held as part of the Scientific St. Petersburg project and supported by the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education.