Spaceships can be divided into two groups: expendable and reusable. The evident drawback of the former ones is that a single launch into space leads to their destruction. The latter aren’t that simple. They do return to Earth in separate modules, but all the devices needed to enable such a come back inevitably make them weigh more, thus limiting the total amount of payload that could be carried on the ship. Cost-wise, reusable systems are more effective, but only in the long-term perspective, as meaningful returns only manifest themselves after several successful launches.

History of reusable systems

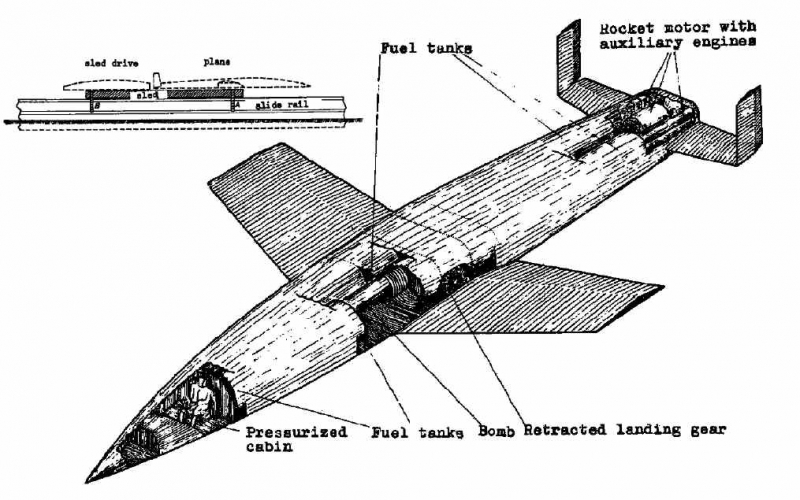

Credits for the first ever design of a multi-use spacecraft goes to Nazi Germany’s scientists. Between 1932 and 1942, they developed an antipodal bomber Silbervogel, also known as the Silver Bird. At the heart of this idea authored by Eugen Sänger was a special mechanism of undulant gliding, which can be compared to the movement pattern a stone makes in a stone skipping game. The craft, it was envisaged, would glide from space in a series of short hops, bouncing back from the drag-producing atmosphere layers. Such mechanism was needed to increase the distance the Silver Bird could overcome in one launch, simultaneously dropping bombs on different targets the world over.

The Germans couldn’t finish the project, but it was later picked up by Americans, who used it for their sub-orbital boost-glide vehicle Dyna-Soar which was mirrored by the Soviet Union’s military project Spiral. Both vehicles were intended to conduct warfare in space. Their other designation was to serve as carriers for nuclear weapons.

But none of the projects came to be implemented in the end. The crucial date of July 24, 1969, which rang out Apollo 11's landing on the Moon, led to a sea change in the superpower relations, although there is an ongoing debate on whether the historic allunaggio actually took place or not. Personally, I agree with the majority of the expert community who say that the landing wasn’t staged. There are too many documents that prove it, and it’s hardly likely that someone would set out faking such an enormous heap of evidence. That famous video is, however, rather more questionable.

Space arms race takes a new turn

Rumors say after Apollo 11’s legendary feat, NASA engineers developed a fear of being left without work and quickly cooked up a large-scale project to prevent it. In 1981, this resulted in the launch of Space Shuttle, a gigantic spaceship equipped with an appropriately huge fuel tank and two side accelerators which are up to this day considered the most powerful in the world.

NASA built lots of Space Shuttle models over the years, but only five of these actually made it into space. The first of the kind, Enterprise, could only boast one pilot launch into the atmosphere. The fourth, Discovery, upped this number to 39. Over their 30 years of being in use, they performed a host of different functions, from carrying out research flights to deploying the Hubble telescope into the orbit and delivering modules to the International Space Station. All but two Space Shuttles made a successful return to Earth. One of these ships ended up burning in the atmosphere, and the other, Challenger, exploded 73 seconds into its flight. All in all, the Space Shuttle program accounts for 135 launches.

Such an achievement was to some extent due to the fact that Americans have more luck with their launching and landing areas. First, they’re closer to the equator, which enables them to get away with a 15% smaller spacecraft engine capacity than the one we need to launch a similar payload into space. Second, they have an ocean to land vehicles into, while Russians have to make do with Kazakh steppes. Water provides for a much better landing platform than firm ground does.

The USSR aimed to challenge the resounding success of Space Shuttles by launching the Energia Buran space program in 1974. It was headed by an accomplished engineer Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy, who also was the one to oversee the aforementioned Spiral project. He decided to fight the enemy with their own weapon, producing a huge reusable ship with the same payload capacity but more powerful engines.

What Soviet engineers did for Buran control-wise was that they had created something similar to modern artificial intelligence. It was this that played a crucial role in navigating the spacecraft during its one and only flight on November 15, 1988. Because of bad weather conditions, the AI decided to forego the official plan of landing from up north, instead turning around and landing from up south. The engineers got so frightened that they considered blowing the ship up altogether, but changed their mind and gave the AI pilot the second chance. The landing turned out to be successful. Pilots of the MiG fighter aircraft which were accompanying the ship during that famous touchdown say the system behaved every bit as a real pilot would, coming down on one wheel first, then checking the situation before coming down on the other.

Impressive both in their weight and payload capacity, Burans could have allowed for building several lunar bases and traveling to Mars for a good measure. But the initiative was too expensive for 80’s Soviet Union, appearing way ahead of its time. So for all of its colossal powers, Buran failed to be put into operation.

Looking to the future

Everyone has probably heard of Elon Musk’s SpaceX reusable space systems, the carrier rocket Falcon 9 and the Dragon spaceship, which have been contracted by NASA to deliver various payloads into the orbit. Although they do their job just fine, I don’t have that much faith in the Dragon 2 model which, as the company plans, will launch people into space. Musk doesn’t seem to fully grasp the fact that transporting people is a task much more nuanced than that of just hauling fuel and supplies from the International Space Station. But as a science popularizer, Elon Musk still has my utmost respect. Few things are as interesting as watching live streams of SpaceX launches and landings. As quipped by one Japanese Sci-Fi writer, an American space program is a TV show, while a Soviet or Russian one is a conquest of Siberia.

Despite this, I believe that the future of space exploration belongs to international cooperation. If we want to get to the Moon, Mars and faraway solar systems, we have to abandon our age-old biases and work together. And civil cosmonautics can play a huge role here. One example of this are nano sputniks such as CubeSat. Massively gaining in popularity, they can consist of one, two or several units, or cubits, which makes it possible for anyone to assemble them and launch them into space The schoolchildren who studied in Sirius this summer tried this out during their stay. Their very own sputnik has been successfully orbiting the Earth for four months now, gathering useful data. Space becomes closer to us, which I’m very glad of.