Much as the majority of events this year, GECCO had to change its format to the online one. Over the course of four and a half days, evolutionary computation specialists were exchanging their achievements and discussing the most topical issues in their field.

“Evolutionary computation is a way to solve extremely complex tasks, so complex that they can’t be adequately solved by any other methods,” explains Maksim Buzdalov, the head of ITMO University’s Evolutionary Computation laboratory. “By first approximation, it’s a way to apply different metaphors, such as evolution, natural selection, mutations, and crossing, to the solution of complex tasks. A potential solution is coded as some species and then it evolves somehow. Sometimes other metaphors are borrowed, for example from physics or collective behavior. Various algorithms are invented which use not so much these metaphors as the accumulated understanding of the solution process, so that one algorithm could solve a wide range of different tasks.”

The GECCO conference has now been held for over 30 years. It features reports both on evolutionary computation and genetic programming, real-valued optimization, combinatorial optimization, and other related topics. This year, the total number of program-featured reports, including full presentations, short poster reports, and workshop reports, has surpassed 350.

“GECCO is the second largest international conference on evolutionary computation, and the first in significance,” says Maksim Buzdalov. “The most pivotal results, those that everyone in the field needs to be aware of, are presented at none other than GECCO.”

In recent years, ITMO University researchers have been regularly presenting their scientific achievements at this conference.

“Our university is starting to be recognized as a university with a good scientific record,” comments on the importance of regular visits there Maksim Buzdalov. “I vividly recall how last year, when our delegation – about a dozen people – was walking by, people would recognize us and joke that the Russian mafia had come. Our constant presence in this field shows the contribution Russian science makes to it – that we’re there and constantly bringing interesting results. I think that we’re already perceived as a scientific school and treated accordingly, which is worth a lot.”

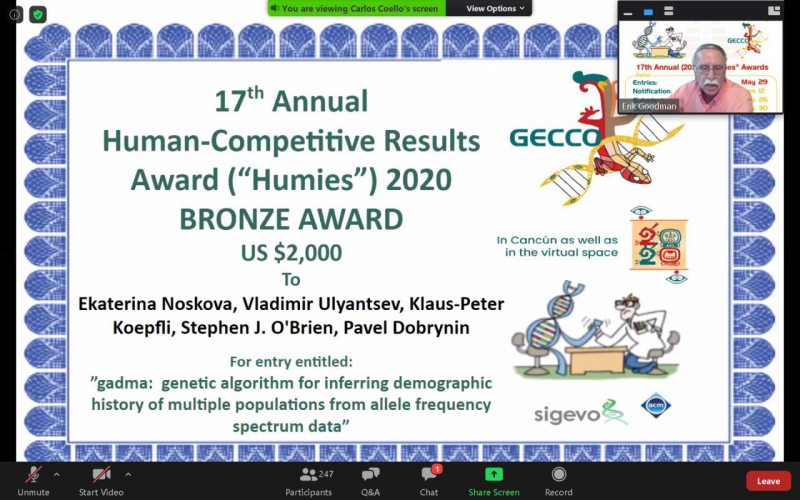

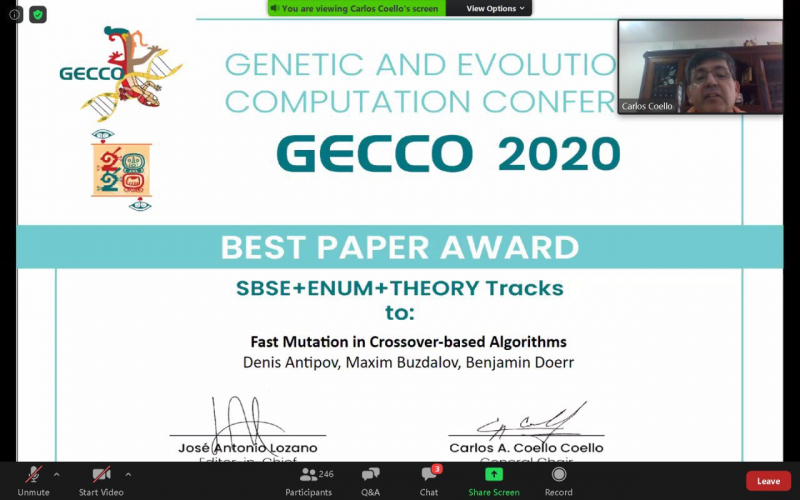

This year, two papers by ITMO University scientists were singled out with awards. For one, in the Human-Competitive nomination a bronze medal was awarded to a team including ITMO’s Ekaterina Noskova, Vladimir Ulyantsev, Stephen O’Brien, and Pavel Dobrynin. Another team of researchers that included Denis Antipov and Maksim Buzdalov received a prize for the best paper in their field. ITMO.NEWS asked the researchers about their work.

Ekaterina Noskova

engineer and researcher at ITMO University, bronze medalist in the Human-Competitive Results Awards category

About the competition

The award that we’ve received was founded in 2004 and has been given out annually as part of the GECCO conference ever since. This is a competition for already published papers dedicated to something human-competitive, in other words, methods that enable automatic solution of tasks that previously required humans to solve them. What’s more, the obtained solutions are better than those that could have been proposed by humans.

The competition is held in several stages – first, you have to send in a description of your paper, then finalists are chosen and tasked to make a presentation and deliver it at the conference. Based on the results, the jury awards three, sometimes four, prizes.

About the scientific results

We presented our work on a genetic algorithm facilitating the search for populations’ evolutionary histories. Our new method automatically builds such histories from genomic data. Before our work, this had to be done practically manually – different models were selected, then optimal parameters for these models had to be found, following which they would be compared to each other.

Our algorithm makes it possible to avoid the entire procedure – everything takes place automatically, no sorting through models has to be done, you just have to launch our software and enjoy the history generated. Secondly, we conducted experiments on the data for which evolutionary histories had already been built in existing papers using the old method. And we managed to show that practically in every case it was possible to find something better than what had been found. We ran 47 different experiments and it was only in one of them that we failed to come up with something better than the original work proposed. On top of that, our results allowed us to uncover some new information about the history of various populations – for example people.

We’re carrying on with checking the histories that have been obtained in the course of other research works and we only very rarely find that they truly are the best. That’s why our method will make it possible to obtain an impressive amount of new information on how different populations and species have been developing.

About the conference

It was my first time participating in an event like this, which is why truthfully it was just interesting for me to try. This year, because the conference was held remotely, we recorded our presentation with the help of a professional videographer (whom I’m very grateful to). This was also a new experience for me, I was very nervous.

But then I watched other reports and found them really good, so much so that I didn’t even hope to receive anything. Just because there isn’t a specific field, it’s very hard to judge how much a task the project sets out to tackle is complex and hard to solve. But then the results were announced and it turned out that we came in third – this was really great!

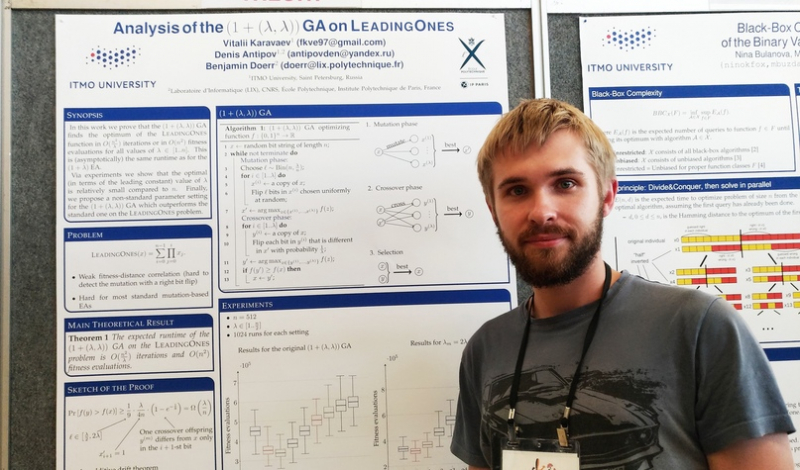

Denis Antipov

ITMO University programmer, laureate of the GECCO-2020 Best Paper Award

About the award

The majority of scientific conferences have the custom to recognize the best presented works with a so-called best paper award. At GECCO, up to three nominees are selected in each section, and then put to a vote by participants who pick the best research projects and results.

Nominees are determined by a narrow circle of the best specialists in the section’s topic. In the case when few papers are featured in one section, several sections are grouped together. This means that the competition becomes more intense, as prizes are vied for within several scientific communities and not just one. We can say that getting the best paper award reflects its being recognized by the wider scientific community for its significant impact on current research.

About the scientific results

Our paper focuses on the theoretical analysis of evolutionary algorithms. To describe this process mathematically and draw some conclusions on how much time an algorithm needs to find the optimum is oftentimes a difficult task. Our work had additional complexity to it – we researched the efficiency of random dynamic selection of parameters at each iteration.

Unexpectedly, it turned out that this random selection of parameters works better than any static selection. What’s more, experimental research demonstrated that such a strategy for the dynamic selection of parameters is effective not only in model problems on the basis of which the theoretical analysis was carried out, but also on more practical problems.

The running time of evolutionary algorithms strongly depends on the values of algorithm parameters, and in order to ensure maximum efficiency it’s necessary to choose the parameters on the fly. A defining feature of our work is that we were first to prove the high efficiency of the method of dynamic selection of algorithm parameters, which implies that at each iteration we choose one of the algorithm parameters in accordance with the power law with certain parameters.

Despite being seemingly simple, this method proved to be as effective in solving the OneMax model task as the best methods proposed previously. In addition, these methods were somewhat geared towards the task. For example, solving more practical tasks called for introducing additional limitations on the values the parameters could potentially take. The algorithm we proposed works right out of the box, including in solving more complex practical tasks.

We showed that choosing a parameter via random distribution is very interesting for practical use. In an earlier work revolving around a simpler algorithm, it was already demonstrated that such a method could remove the need for the algorithm user to search for the right parameters without any tangible loss in productivity achieved with the optimal choice of the algorithm’s parameters (which isn’t often possible in practice).

Now, when we’ve shown that this parameter choice method could even improve the algorithm’s running time, we hope that it will be successfully applied in the solution of complex practical tasks, too. We’re continuing our research as part of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research international grant No. 20-51-15009 titled “Theoretical Foundations of Dynamic Parameter Tuning in Evolutionary Algorithms”.

Personally, I consider this to be a huge achievement for me, one that culminates my PhD studies. When the winners were announced, I was even happier than I was when Liverpool struck its fourth goal against Barcelona. I’m very pleased that the idea my scientific advisors and I came up with was so well accepted by the scientific community conducting research in evolutionary algorithms.