What was your motivation for the trip?

Egor Matsuev, Master’s student at the Faculty of Control Systems and Robotics: A few weeks prior to the trip, I got interested in the Japanese language. I practice Aikido, so I had already known quite a lot of words in Japanese by the moment I started learning the language. Japan has a very unique culture, and I really wanted to take a closer look at it, meet the locals, visit different cities.

Elena Kislitsina, PhD student at the Faculty of Control Systems and Robotics: I travel a lot, but mostly in Europe. I was a bit scared to visit Asian countries, as their culture is so different from ours. But then a moment came when I decided to give it a try and embark on a voyage to Asia. Japan seemed like the best option as it is one of the most developed countries in the region. That was when ITMO University opened submissions for this exchange program, and I grabbed the chance. To be honest, I didn’t know much about Japanese culture before the trip except for maybe geishas and samurais.

Tatyana Lyalina, Master’s student at ITMO’s Biochemistry Cluster: My research advisor Prof. Dmitry Kolpashchikov worked in Japan for a couple of years and has told me a lot about this country. That’s how I started thinking about traveling there. Thanks to this program, I could not only go there but fully immerse myself in Japanese culture: we were almost always accompanied by Japanese students and the schedule was pretty tight.

Daniil Shirokov, Master’s student in Science Communication: I started watching doramas and reading manga when I was a kid. I still read it now, together with research articles, of course. So I guess I’m a real otaku. Later I started studying Japanese history, and even ploughed through the Cambridge multi-volume history book and tried my hand at writing Haiku. However, when I first learned about this program, I didn’t want to apply. It was my friends who made me. And then I met Olga Ovsyannikova from the International Office who helped me with all the paperwork. I’m really thankful to her for that.

What surprised you most?

Egor Matsuev: The Japanese are very different from us, they are extremely polite and good at following routines; whatever they do there is always a certain order, even if it’s something as trivial as sorting and packing luggage in a bus. They care a lot about environmental protection; there are very few trash cans in public places, but the streets are clean. I think that it’s simply not in their nature to litter, and they don’t. While in Russia there are many trash cans, but the streets are still littered. As for the politeness, I was really surprised when the family I lived with gave me a very unusual and rather expensive gift, an element of a traditional Japanese clothing. Just think about it: people went to the shop and bought these things for us. Japanese students gave us presents, too. The only problem here is that you never know if they really wanted to give you a gift or just thought that it would be inappropriate not to.

Elena Kislitsina: We’ve all heard about the Japanese social hierarchy, and it’s true: they deeply respect their elder relatives and colleagues. No crucial decisions are made without their approval. Japanese always follow the instructions given by their bosses. For one, during our trip, the program managers decided that it would be good for us to visit a company that produces hygiene and disinfection products using eco-friendly technologies and materials. The program’s coordinators were ready to go above and beyond to follow this instruction, and our schedule was changed significantly. The trip turned out to be very interesting though: we were told about how people in Japan promote environmental protection both inside the country and abroad.

In general, the Japanese are very sensitive to nature. In Nagasaki we sailed to the island where there used to be a coal-mining station; the way to the island runs along beautiful mountains and pristine small islands. There are not so many uninhabited territories in Japan, but it’s very clean. People live in small spaces, but they treat each other with respect, defer to others’ opinion. 30 million people live in Tokyo, but the streets aren’t crowded.

Tatyana Lyalina: I was surprised by how organized and efficient the Japanese are. We had a jam-full program agenda, but everything was very well arranged and thought-out. What was most difficult was the language barrier. I knew that for a long time Japan was a country closed-off from the outside world, but still hoped that English as the world’s lingua franca had found its way in here, too. But it wasn’t as widespread as I expected: only a few Japanese I met could actually speak English. But the majority of people in our group of Russians, us and some other students excluded, knew some Japanese, so they could communicate with locals and kindly translated things to us. However confusing, this experience was still very helpful to me as it made me realize that you can understand and connect with someone even if you don’t know a smidgen of their language. It was an extremely valuable and rewarding experience of intercultural communication.

Daniil Shirokov: Apart from the amazing culture, interesting people, convenient and organized way of living, and the abundance of miniature things, I’ve also been impressed by the sheer ubiquity of the vending machines. You can find them everywhere you go, be it the Tokyo city center or Nagasaki harbor, standing left and right two minutes away from each other. The other thing I noticed was how humane the payment control system in Japanese metro stations is. In Russia, in Moscow especially, if there’s something wrong with your payment, you and everyone else will immediately become aware of it thanks to a deafening alarm signal shuttering the metro station walls. But it doesn’t just end there; what comes next are the mighty ticket barrier gates seemingly programmed to punish hapless metro users by crushing their bone or two. In Japan, however, the alarm signal is much more quiet and peaceful; it sounds as if it wants to say that a mistake has occurred, rather than hysterically demanding others to stop a violator. And their ticket gates are like a couple of soft Ikea pillows that gently tap your legs if something goes wrong.

What was your day-to-day like?

Egor Matsuev: As part of the program we visited Osaka University, where we attended a lecture on the comparative analysis of Russian and Japanese economies. The lecturer noted that the Japanese yen has a very stable exchange rate that hasn’t changed for some twenty years now; he also described an average Japanese working day and unveiled some economic statistics. We’ve also been to the Russian embassy in Tokyo, where we met with the Russian ambassador to Japan who told us that Japanese have a very warped understanding of Russia due to their media’s nitpicking and negative coverage of the country. But the Japanese who have actually been to Russia always say how pleasantly surprised they were. That’s why the Russian embassy’s main goal is to change Japanese perceptions of Russia. This is also the rationale behind the Japan-Russia youth exchange program.

Elena Kislitsina: All the way throughout our program, we were guided by Japanese students, who accompanied us everywhere we went. They told us lots of interesting things about the Japanese life and culture, for example, that the Japanese choose their future career path as early as in childhood and then methodically and persistently head to their goal. I’ve seen it myself; I met a teenager there who was really into aeronautical engineering, he’d been exploring it for 10-15 years and so already knew a lot for his age. That, in turn, had sparked his interest in Russia as our country has a rich aeronautical history and expertise. Japan has top-notch universities, but there’s no such thing as free higher education and it’s really hard to get in; even harder is getting a scholarship. Scholarship is something out of ordinary, and it’s a huge accomplishment to be awarded one.

We took every opportunity to immerse ourselves in the Japanese culture. On one particular day, we spent more than twelve hours walking around in traditional Japanese clothing, yukatas. We slept on futons, which are a special type of mattress put directly on the floor. It was surprisingly comfortable. Because hot springs are so widespread, the Japanese love to take hot baths, especially open-air ones, which are called onsen. Japanese girls pay a lot of attention to how they look; public baths abound with mirrors, as well as different oils and other skincare products, and the interiors are beautiful and very well-designed.

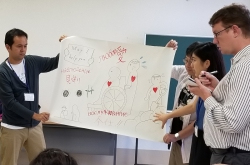

Tatyana Lyalina: Each Russian student had a Japanese buddy helping them deal with all the problems and make the most of their stay. Upon our arrival to Japan we were split in different teams, each having a bespoke cultural program. Ours included attending a traditional tea ceremony and a tea factory, as well as exploring the Atomic Bomb Museum. Going to Japan, you’ll have to be mindful of the Japanese climate that is very different from ours in Russia: August, for example, is really muggy and hot, and there’s a high risk of typhoons occurring.

Daniil Shirokov: What seemed most peculiar to me was the way the Japanese dress. The majority of locals I’ve seen wear official work-style costumes all day every day. I was prepared to see some crazy garish outfits or something really trendy at least, but the reality was very different from my expectations, and sometimes it just looked too same-y and weird. Apart from that, I was amazed by this mixture of self-discipline and respect that characterizes Japanese culture. Japanese people know how to queue, they never take other people’s places, nor do they push or argue. But giving up your seat in metro trains and buses is not in the Japanese custom. I attempted to do this once for an elderly lady with a child, but it took her some time to understand what I was doing, and she didn’t want to sit down until my buddy Hiro told her that in Russia not to take the seat means showing disrespect to the person that cedes it. So the lady hastily took my place, because respect is the number one quality cherished by all Japanese.

Wondering how you yourself can participate in the Japan-Russia youth exchange? Here’s our step-by-step guide to help you out!