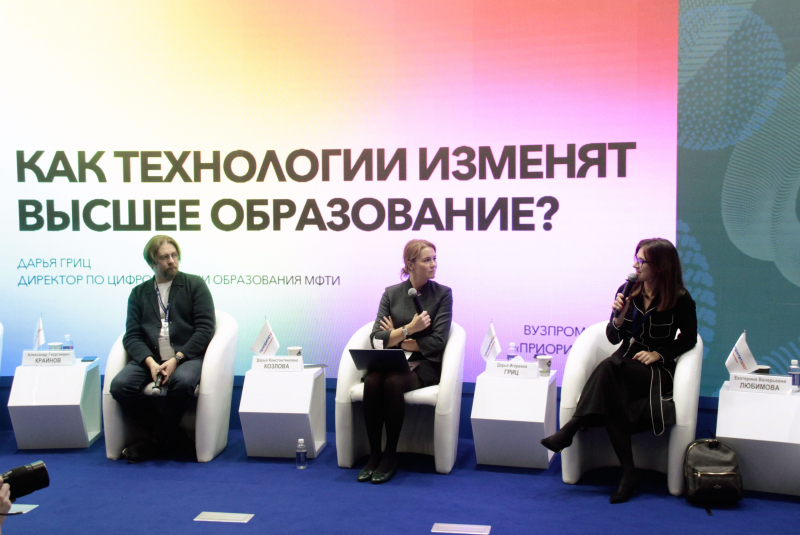

The discussion involved Darya Grits, the director for digitalization of education at MIPT; Alexander Krainov, the director for development of AI technologies at Yandex; and Ekaterina Lyubimova, the vice rector for education at University 2035.

First, the speakers touched on the topic of resistance to changes, especially when it comes to online education, within the system of higher education. As noted by Daria Grits, this resistance has little to do with the technologies themselves. The main changes that occur today and will take place in the future will have to do with the organizational and business models. And the primary challenge isn’t integrating new tools – such as learning analytics or recommendation systems – but convincing university administrations to reorganize of their own volition.

The future of education lies in utmost transparency, says Daria Kozlova. To ignore the opportunities offered by remote learning tools and the internet in general is to lose the technology race.

“Technologies push us towards becoming more transparent. There's just no other way. The future of education is in network solutions that allow students to extend their learning tracks beyond the limit of their own university. Those universities that will be first to realize that cooperation and exchange are more important than competition will be the ones to win,” emphasized the First Vice Rector of ITMO University.

Daria Kozlova. Photo by Ekaterina Shevyreva for ITMO.NEWS

According to Dr. Kozlova, in today’s rapidly changing world the role of universities is to validate content. After all, they possess the necessary expertise and experience. But this knowledge needs to be combined with a readiness to change and quickly respond to the needs of students and the industry alike.

“A university is a trusted institution. At least that’s the case with ITMO: everything we offer to students passes our own checks first. We take specific, niche educational modules from Yandex and JetBrains and layer them on top of the core university curriculum. We do it dynamically, without the need to rework the educational standard. I’m all for this kind of academic mobility within educational programs,” commented Daria Kozlova.

But how should a university establish partnerships with leading tech companies such as Yandex – the dream employer for any graduate? Alexander Krainov says that the company pays particular attention to the students’ scientific background and their ability to navigate the latest advances in their field.

Alexander Krainov. Photo by Ekaterina Shevyreva for ITMO.NEWS

“Any developer at Yandex has a whole stack of recent articles and conference proceedings on their desk. A part of their job is to read the latest publications and absorb their findings. Sometimes, they publish their own work, too – a quarter of all Russian publications at top conferences comes from Yandex staff. This means that if we hire someone, they must be at a level where they’re capable of writing a proper scientific article. We expect the same of our interns, too. Experienced developers don’t work on breakthrough cases – they do tasks that must be done by default. The risky and complex tasks fall to interns because they have the right to make mistakes. Interns must be able to make world-class breakthroughs,” explained Alexander Krainov.

He also added that, in light of the many online tools and independent learning opportunities available to students, a lecturer’s job is, first and foremost, to set a high bar of excellence for students and bring up specialists more talented than themselves.

At the conclusion of the talk, the speakers discussed ways to assess the effectiveness of education. The entry threshold for an educational program can be quite low, but the exit threshold must be high, as beyond it are employers and strong competition. Therefore, the basic indicators of educational effectiveness must be the answers to two questions: where does the graduate work – and what have they achieved?