The official name of my lecture is “Fingers, skull, hammer. Modern pseudoscience on innate abilities of humans”. You might think that it focuses on exposing pseudosciences and advising against dealing with chiromancers. Instead, I’ll be explaining why promising trends in science falter times and times over, all because of intolerance to criticism and human ignorance. We’ll use two pseudosciences as examples: dermatoglyphics that studies human talents based on dermal ridge patterns, and phrenology that focuses on searching for correlations between the shape of peoples skulls and their innate abilities.

What do we know about patterns on fingers and palms?

First of all, they are unique for every person, and there seems to be no pair of matching fingerprints in the whole world. Truth to say, that’s impossible to prove. Still, judging by statistics and features of fingerprints, we can well say that it’s highly improbable that two people with the same fingerprints will meet in the same historic period.

Although fingerprints are unique to every person, there only exist three types of dermal ridge patterns: loops (the most common one), whorls, and arches. This offers an opportunity to classify them, create associated databases and conduct biometric scanning.

Another thing that we know for sure is that capillary lines in palms don't change over one's lifetime. You are born with a particular skin pattern and number of dermal ridges, and they stay with you for the rest of your life. There is sometimes news in the media about research that disproves it, and that these patterns can change. Still, if you read the research thoroughly, you'll learn that it had to do with errors of identification: sometimes, a person can eliminate particular patterns due to the events of their life. The simplest example here is getting scarred.

By the way, what’s the purpose of dermal ridges?

There exist two hypotheses on this issue. The first implies that dermal ridges improve the traction with a surface of any object that we hold in our hands. Patterns on the palms of capuchin monkeys have a similar purpose: they help them grasp tree branches better. On the other hand, experiments with human skin showed that in reality, dermal ridges don't contribute much to traction in neither dry nor humid climate conditions.

It's more probable that dermal ridges enhance the sensitivity of particular receptors, and this is why they are located on the parts of our bodies which are usually used for manipulating objects. They had the very same purpose some 10, 20 and 40 million years ago. Similar patterns can be seen on the skin of every type of primates that existed before us.

So, patterns most probably enhance receptors’ sensibility. Is there any other purpose? At different times, researchers from different countries focused on this issue, and some came up with the idea of using these patterns to identify our innate abilities and traits of character.

Such techniques have become very widespread since the 80s in different parts of the world, especially in India, China, Nepal, Bangladesh, and here in Russia. Still, in every country, they have their peculiarities. For example, dermatoglyphic testing in India and China is based on a totally wrong idea that there's a correlation between the complexity of patterns and development of particular areas of the brain. Still, no one cares to explain why it is the index finger that’s connected with the frontal lobe.

On dermatoglyphic testing in Russia

In Russia, this pseudoscience has a more complex formula. It is assumed that skin and the nervous system are formed from the same kind of tissue at the same time. Also, statistics that are based on a huge database on sportsmen, scientists and artists show that there's a difference in dermal ridge patterns of representatives of different professions. Therefore, fingerprints can tell of their owner's professional field and personal traits and can be used to forecast one’s innate abilities. In particular regions, they even conduct such tests at shopping malls, and the staff advises parents to test their children so that they know which path they should take in life.

Three years ago, the Committee for Pseudoscience Control of the Russian Academy of Sciences released its Memorandum 1 that focused on busting dermatoglyphic tests.

In accordance with this document, we can no longer say that there's research that proves the efficiency of dermatoglyphic methods for assessing innate abilities. Authors of dermatoglyphic tests often call their system “genetic”, which would mean that dermal ridge patterns are hereditary. In reality, this issue is yet to be proved. The dermal ridge patterns are different even in identical twins. Therefore, it is not only genetics that plays a role in forming then, but prenatal development, as well, and there is no direct relationship between genes and dermal ridge patterns.

How manipulating statistics helps find correlations between everything and anything

In 2010, an American neurobiologist Craig Bennett and his colleagues published curious research. They put a body of an Atlantic salmon into an MRI scanner and showed it photographs with images of faces of humans in different emotional states. From time to time, they got readings of its brain. It turned out that the fish could discern particular emotions: when it was showed particular types of images, a particular area of its brain got excited. Still, the most curious thing about this research is that the salmon was dead!

The research got the Ig Nobel prize, as it is great at proving the thesis that when conducting statistical analysis, you need to make an adjustment for multiple comparisons, otherwise you’ll be compromising your results. You can even get false statistically significant correlations if you compare enough objects.

For one, there is a correlation between the number of people who drowned in pools and the number of movies starring Nicolas Cage. The level is quite high, higher than 0,9. Another example: there’s a correlation between the USA's expenses on sci ce and technology and the number of suicides by choking and hanging across the world.

After the publishing of the Memorandum, there emerged many articles in the media where not just dermatoglyphic testing, but dermatoglyphics itself was deemed pseudoscientific. The testings’ adherents and authors also took action by claiming that the Memorandum’s authors had been bribed and there was proof that there are correlations between dermal ridge patterns and innate abilities.

Phrenology

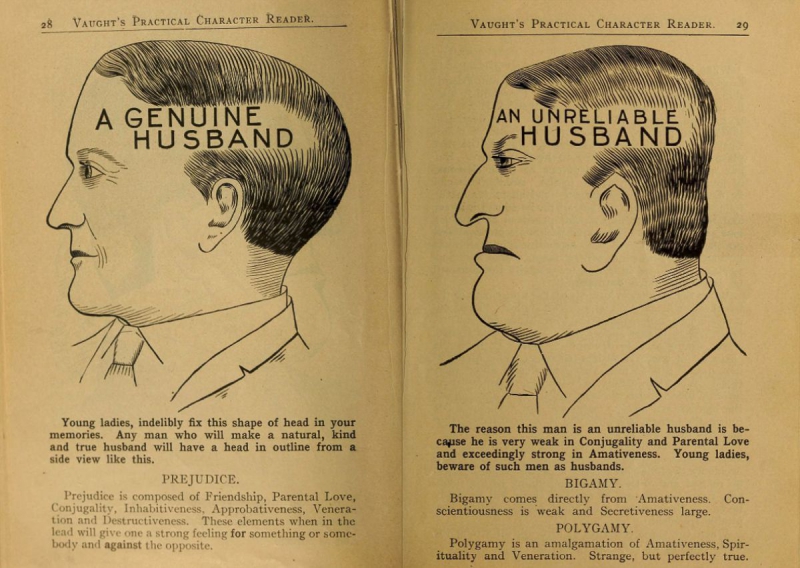

Now, let's take a look at another pseudoscience. Phrenology appeared in the late 18th-early 19th century. Supposedly, it was founded by Franz Joseph Gall who assumed that the brain is not a homogeneous organ. He believed that different areas of the brain are responsible for different abilities and traits. At that time, the idea was quite novel.

Gall was no charlatan (as opposed to his followers), but he was wrong. He identified the correlation in a most random manner: by his experience of meeting various people.

For example, he had a student who liked dissecting animals and eventually became a surgeon. When Gall examined his head, he found prominences above his ears. The scientist decided that this area is responsible for destruction, and its development helps a person become a surgeon or commit murder. Gall used the same approach when identifying areas responsible for other traits, as well. He worked in prisons and mental asylums and gathered a lot of data on different features that make particular peoples skulls different from those of others.

Similarities between dermatoglyphics and phrenology

According to Gall, the more convex an area is, the more developed is the associated trait. And here we can see similarities between dermatoglyphics and phrenology. In both cases, a more intensely developed trait corresponds to either a more complex shape of a skull or a more complex dermal ridge pattern.

Though there are almost two hundred years between the emergence of these pseudosciences, their essence and logic of researchers are quite similar. Both sciences got recognized by particular representatives of the scientific community. Dermatoglyphics was supported by scientists who work at institutions of the Russian Academy of Scientists and universities. They publish research articles that are included in databases and cited by others. Phrenologists also got published in real scientific journals, published books and delivered lectures. In the 1930s, there were over 30 phrenology societies in Europe, with over 1,000 members. And many of them were people of different professions: doctors, psychiatrists and attorneys.

Much as in case of dermatoglyphics, phrenology doesn’t feature any real assessment of its method’s prognostic value. None of the researchers ever conducted statistical analysis. Even the book called “The Statistics of Phrenology” by phrenologist H.C. Watson doesn't contain any statistics despite its name.

Shortly after the emergence of their field, phrenologists focused on practical applications. They started to look for the social circles and group they could use to make profits from their method. For example, particular politicians we ready to defame their opponents by speaking about the improper form of their skulls.

By the way, several years back the Russian Federal Agency for Physical Culture and Sport supported the publishing of a book for parents on how to measure their children’s potential success in different types of sports based on their dermal ridge patterns. These correlations are yet to be proved, but the book is already being published.

Surely, this is not an issue of pseudosciences only. In modern times, almost every reproduced study fails to show the same results as the original one. This is true for 70% of pharmaceutical research and 60% of experiments in the field of social psychology.

It all happens due to our human disposition towards searching for evidence of hypotheses that we find likable.

Is there any future to scientific attempts to forecast humans’ innate abilities?

Sure. Even now, scientists continue to research this subject. There are projects in the field of genetics, tests on identical twins, and experiments with offering children marshmallow. People are interested in learning new things about themselves and their future. Nevertheless, every time you plan to introduce the results of a research, you should ask yourself: I am really sure that I don't just pander to common misbeliefs and a desire to prove an idea that you like.