Staff members Ilya Livshitz, an associate professor at the Faculty of Secure Information Technologies, Aleksandr Maiatin, deputy head of the Information Technologies and Programming Faculty, Yana Muzychenko, deputy head of the Faculty of Physics and Engineering, Anastasia Pavlova, a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Food Biotechnologies and Engineering, Elena Budrina, a professor at the Faculty of Technological Management and Innovations, and Antonina Puchkovskaia, head of the International Digital Humanities Center, presented their reports during the meeting.

Participants shared different takes on distance learning. Various ITMO staffers’ impressions ranged from “an interesting experience” and “a challenge” to “an emergency” and “a source of stress.”

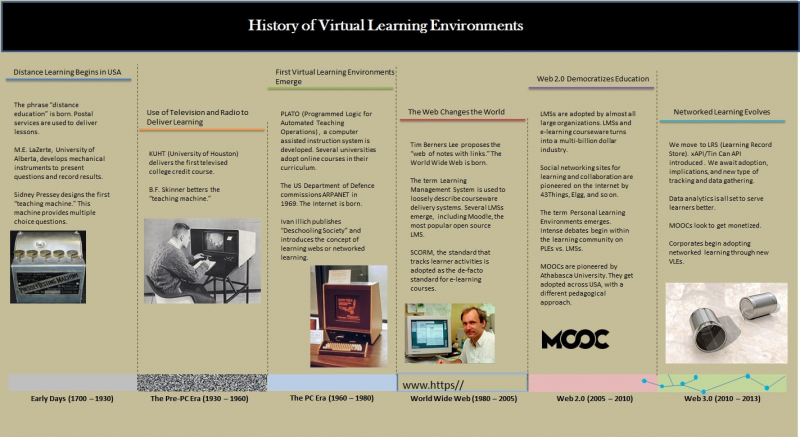

Of course, all things new cause fear and concern – but distance learning is far from new. The first mail-in educational courses emerged in the 18th century with the establishment of extensive postal networks. Students would complete assignments and submit them by mail in a process that would stretch for months on end, partly due to difficulties with communication at the time. In the mid-19th century, the first distanced university program was set up for students of other campuses and universities.

In the 20th century, as cinema, radio, and television developed, humanity adopted new formats of communicating information. 1948 marked the appearance of the first radio-based educational program, and the first educational TV channel that featured various courses and mail feedback was launched in 1982. The first online course became a reality in 1984, while the first online university opened its figurative doors in 1994. In 2000, international programs began to emerge that already adhered to all modern hallmarks of distance learning.

Throughout the discussion, which continued for over two hours, the speakers reached several conclusions. They highlighted subjects that should receive special attention in order to improve the quality of distance learning at ITMO.

Technical equipment. Equipment is a crucial element of education, moreso in the digital format, where success is impossible without the proper software, devices, and digital tools.

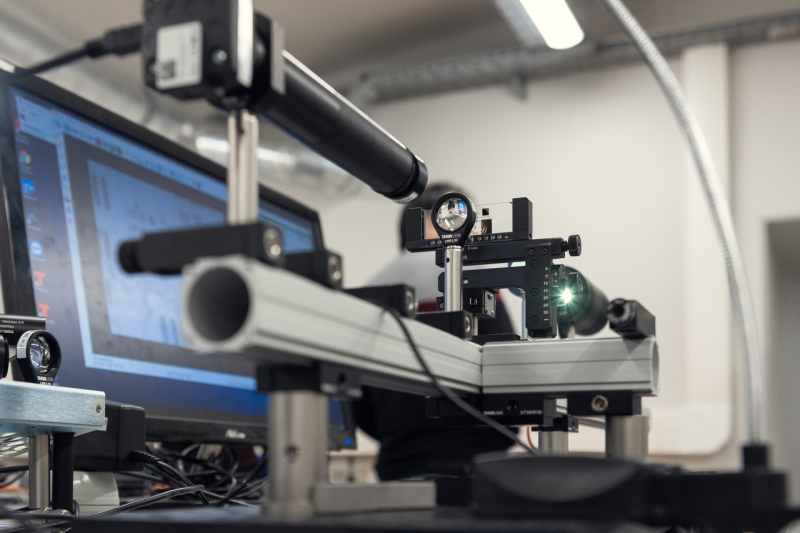

“Lab assignments in the remote format were a real issue, and we instantly felt skeptical towards virtual ones. We at the Faculty of Physics and Engineering decided not to implement them, as they’ll never be a good substitute for in-person practical training. To the students, we suggested the following options: conducting simple experiments at home; processing data collected from equipment at the lab; or remotely accessing our lab systems (a widespread practice abroad, but less common here),” says Yana Muzychenko, deputy head of the Faculty of Physics and Engineering.

Digital competencies. The better the staff and students are at using digital tools and are familiar with software that makes experiments shorter and more productive, the better the end result.

“Back in March, many of my colleagues, myself included, didn’t even know what Zoom was. But, naturally, we got a grasp of it soon. In the spring semester, classes were set up like this: first, we’d decide on a mode of communication, I’d share my contact info, and we’d settle on the class format (lecture or practice). Throughout the studies, I’d need to evaluate the quality of the course: whether everything’s in sufficient amounts, if it’s accessible, if the practical examples are relatable,” shares Ilya Livshitz, an associate professor at the Faculty of Secure Information Technologies.

He also adds that the main challenges faced by the teaching staff concerned the students’ level of involvement, especially during theoretical lectures; monitoring the quality of classes; and teaching to mixed-language groups.

“One effective solution we’ve found for challenges prompted by distance learning is the risk management funnel – at the beginning of a course, we draw up a plan of where we want to be by its end. This way, students always have some sort of guide and point of reference regardless of the changing circumstances,” adds Ilya Livshitz.

Aleksandr Maiatin, deputy head of the Information Technologies and Programming Faculty, also touched on the subject of student involvement and motivation.

“Top-tier school graduates who apply to ITMO didn’t choose it for lectures, which they could find on Coursera or MIT OpenCourseWare, but to meet the staff here. Distance learning rids them of this precious opportunity. But we should still strive to give them what they want – otherwise we’ll lose their interest and, therefore, motivation,” he says.

He shared his experience of setting up lectures and lab assignments in the distance format, as well as monitoring them. His first piece of advice concerned student involvement: instead of being equivalent to pre-recorded video, lectures should be as interactive as possible, perhaps in the form of a Twitch stream during which students can discuss various topics and ask questions.

Another tip touches on lab assignments: these should be conducted in parallel Zoom rooms – one for frontal instruction and another for students’ individual presentations.

Aleksandr’s third tip concerned monitoring of tests, which remains an issue despite the existence of tools such as Olymp. He also brought up a number of other issues, such as educators’ copyright in the context of distance education, implementing rest breaks for students and staff, and providing classrooms with all the necessary equipment.

Planning and design of the educational process. University isn’t all about lectures, watching videos, or repeating the topics presented by the teaching staff. The educational process should also include individual and group work, as well as encompass theory, practice, research, and so on.

“On March 16, our lives changed completely. Every educator had to quickly figure out their plan of action for the near future. I was caught unawares. I had to redesign lectures in order to relay the most important information without losing my connection with the students. Every one or two slides, I’d ask short questions to check for responses and set up question-based contests in Zoom. But the approach to practical classes had to change, too. The standard 5-10 page lab assignment descriptions became unacceptably large,” says Elena Budrina, a professor at the Faculty of Technological Management and Innovations.

She adds that, with time, students began to complain about the number of assignments, which increased sharply because of the perception that studying from home is easier. This situation, too, had to be taken under control. For instance, Elena Budrina created social network pages for the three disciplines she taught during the past semester; on these pages, she would post recordings of the lectures, presentations, and supplementary materials for practical and lab classes.

“By the end of this period, I learned that if you give students the freedom to choose tools with which to complete assignments, share your contact info, and set a deadline, you can get great results. Overall, the students’ general performance was 15% higher than in previous semesters,” she notes.

During the discussion, ITMO staff also spoke about the outcomes of the spring semester’s international projects, conferences, and academic exchange programs.

Antonina Puchkovskaia, head of the International Digital Humanities Center, faced a number of organizational challenges.

“During that semester, we were expecting visits from US professors Kimon Keramidas and Victoria Alexander. Unfortunately, Kimon couldn’t come and we had to deliver his Information Design course together despite the time zone difference. Victoria came to Russia before the isolation period began, so she was able to stay here and deliver the course Quantitative and Qualitative Methods on her own,” says Antonina Puchkovskaia. “Overall, organizational issues were the most discouraging trend of the year. Most ITMO students weren’t able to attend conferences or do internships abroad or go on academic exchange. Some events were postponed till next year, and some held online. This was sad news to us and to the students alike. But, unfortunately, there was little we could change in this situation.”

Anastasia Pavlova, a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Food Biotechnologies and Engineering, shared her successful experience of conducting an international conference online.

“We planned to hold an international environmental conference for students from Finland, Lithuania, and Sweden. Four major companies, two sessions, and two business cases at each. We were able to do the first one, but the borders closed before the second was set to start. But even online, the event went well. This was because we quickly tackled all organizational and technical issues and distributed the roles. It was indeed a very eco-friendly conference: zero flights and rides involved,” she explains.

She also brought up the subject of supporting online courses.

“Before the quarantine began, I published a course on edX: I was lucky to have most of my lectures already online before the pandemic went into full swing. But it was a revelation to me just how much we underestimate distance learning. Over eight weeks, my course had around 850 students (of which 21 received certificates) – and it took me a lot of energy and strength to monitor the process. Online chats and Zoom are peanuts compared to this,” says the specialist.

As the event’s organizing team noted, the discussion, which took place as part of the ITMO.Expert project, provided opportunities to discuss the aspects of distance learning at ITMO that must be considered and improved to ensure a smooth transition into the new academic year.