How did you come up with the idea to create an exoskeleton?

I’ve been into robotics since the eighth grade; I made a radio-controlled tank myself at the time. Then I decided to design something more complex and tried to create an exoskeleton. My grandfather helped me – together we welded the first skeleton out of wire. We manually measured each piece, calculated everything, left marks, and welded the pieces together. So, gradually, we created our first Frankenstein. It had lots of welding scars so it looked kind of creepy. Plus, it lacked stiffness, as it was made out of binding wire. When I reassembled it, I noticed that its back was bent because of the weight.

I took notes from this experience when creating my second exoskeleton – I improved the construction and added new moving points. My grandfather and I ended up building two versions; I’ve designed both passive and active exoskeletons. Now I’m working on my fifth active skeleton.

What is the difference between active and passive exoskeletons?

An active exoskeleton has an additional energy source and it helps the person wearing it with a certain task. They’re in use in the army and the industry. Passive exoskeletons take on only part of the weight that the people wearing them have to carry.

Modern active exoskeletons have an issue – they barely allow their users to move. You can’t run when wearing them, it’s hard to even walk because they are very heavy.

Passive exoskeleton

What was the first weight you lifted using your suit? How did it feel?

It was a lead car accumulator that weighed about 15-20 kilograms. I could feel its weight but for the most part, it was the skeleton that dealt with it. In general, wearing an exoskeleton is like driving – if just one screw is loose, you’ll feel it immediately.

Did you present your project when applying to ITMO?

When I was still in school, I used to take part in the Baltic Scientific and Engineering Competition, Geek Picnic, and the Academy of Digital Technologies. Then I applied to ITMO University and Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University. They noticed my project at ITMO and I was invited to be admitted, which settled my choice.

What was the suit like back then and what’s it like now?

The second version had two key disadvantages: it was heavy and not too movable in the hip area. So I started to design a new version and learned how to make 3D models.

The next prototype was more flexible for people of different sizes and supplemented by additional axes in the back area, hips, and shoulders. The exoskeleton didn’t paralyze its users that much but it still was heavy because of its steel frame.

The third version weighed about 100 kilograms. The one I’m working on right now will weigh about 40-50 kilos thanks to another material, smaller size and the usage of composites.

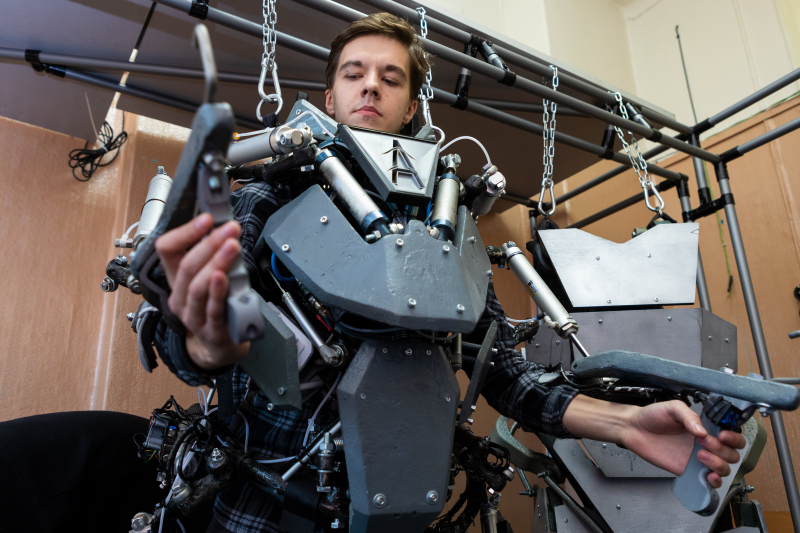

Alexey Ledyukov in the exoskeleton. Credit: Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

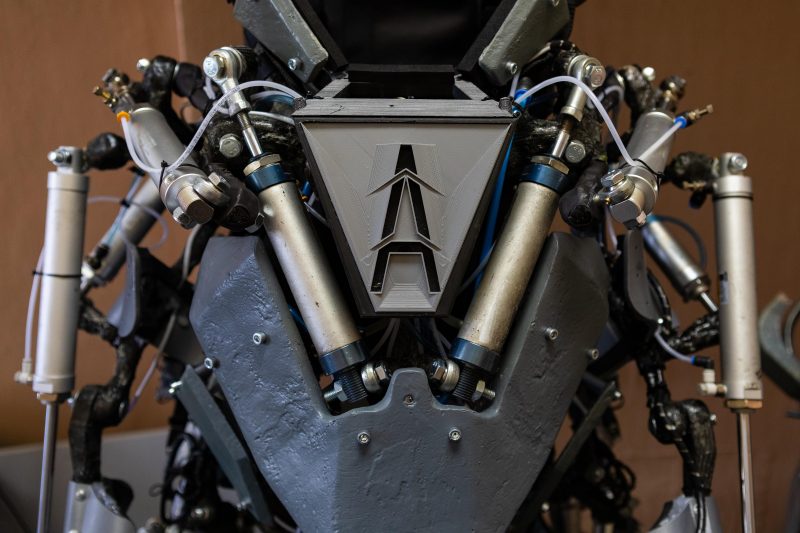

What is it made of?

The carcass is made out of carbon plastic, pneumatic air cylinders – out of steel and aluminum, and bearing pieces – out of hardened steel. Handles and closing elements are made of latten, ABS plastic, and fiberglass.

What are your further plans?

The new version will be more ergonomic and technological. I used to 3D print all pieces and then manually wrap them with carbon plastic and process with a drilling machine. The new model will be molded: we’ll create a silicone form and then fill it with a two-component plastic reinforced with carbon fiber.

How does the exoskeleton work?

When a person lifts their arm or leg, resistive pressure sensors placed in specific places are activated. That’s how the speed and direction of movement are determined. The skeleton doesn’t resist your movements – it moves its drive units in the direction specified by the sensor signals. The signal is processed and thanks to it, the valves connected to the skeleton’s drives get opened and closed. Then, when the user lifts some weight, the direction of their movement changes. The suit understands it and attempts to compensate for the effort: the user will feel the weight but won’t strain their muscles.

Who can wear it?

The new model will suit people with a height of 170-190 centimeters.

Where can it be applied except for the industry and the army?

Another field where it can be applied is rescue services. This suit is quite movable, which isn’t necessary for the industry, where it’s enough to lift weight and be quite mobile.

For the rescue services, however, the suit is of great help – heavy machinery can’t reach a destroyed building until the debris is cleared up. Plus, the suit will protect the workers from falling fragments of a building or high temperatures, if it’s made fireproof.

The Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation is aware of our project and they suggested we test the exoskeleton at a training ground.

Alexey Ledyukov in the exoskeleton. Credit: Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

How many people are there on your team?

Our team consists of six people and each has their own role. There are developers, people who come up with new ideas, and those who express and publish them.

We plan to take part in the Tekhnosreda exhibition in late September. Then we’ll apply for several grants. We would also like to join the ITMO Accelerator and start small-scale production of passive exoskeletons by summer. Plus, we received an order from a client to design an airsoft suit.

How can it be applied in airsoft?

I was surprised too when airsoft equipment companies started to contact us. The suit can be something like a tank that’s not afraid to be shot at. It’s like an imitation of a perimeter breach. Using an exoskeleton will basically make it possible to change the concept of the game that is typically about making one shot on the target.

Have you considered creating an exoskeleton for disabled people?

I don’t have such plans. Modern medical suits are quite good but also pricey. So the developers should simply work on a way to make them more affordable.