In Russia, science art has only recently become a topic of discussion. When did this field gain prominence in Chile and Latin America in general?

It all started in the 1960s. Back then, many artists grew interested in cybernetics and the connection between humans and technology; so, many works touched on the topic. This was also when Juan Downey – a Chilean artist and video art pioneer who later emigrated to the USA – began to exhibit his works. His most famous work, Video Trans Americas, uses collages and non-linear storytelling to examine the issues of self-identity through juxtaposing footage of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon and of New York City.

However, the development of cybernetics in the arts was stunted by various military dictatorships that were installed around 1970 in Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, and some other Latin American countries. Martial law, concentration camps, and repressions – many intellectuals, such as artists, had emigrated, while others didn’t have the chance to create art or engage in research. It had seemed that, after these regimes went away in the 1980s, artists would have the opportunity to return to their work in Latin American internet art. But at the time, there were no computers being made in Chile; rather, they were imported from IBM in the US. This was an expensive technology, affordable only to major organizations like the University of Chile, and thus there were few opportunities to develop when it came to computers.

As the 2000s came about, technology became more easily accessible and more people became interested in science art. Universities in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and other countries began to establish laboratories where students and lecturers could work on their research in this field. Artists were now able to exhibit their works at spaces like the Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico or the international festival FILE in São Paulo (Brazil). Governments, too, provide their support: for instance, the Office of Arts & Culture at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and the nation’s National Fund for the Development of Culture and the Arts, too, award grants to artists.

Many young Chileans are into both science and art and they don’t want to choose between careers as scientists and as artists. Instead, they want to combine these callings. For now, the Chilean science art community, just like its Russian counterpart, is still developing.

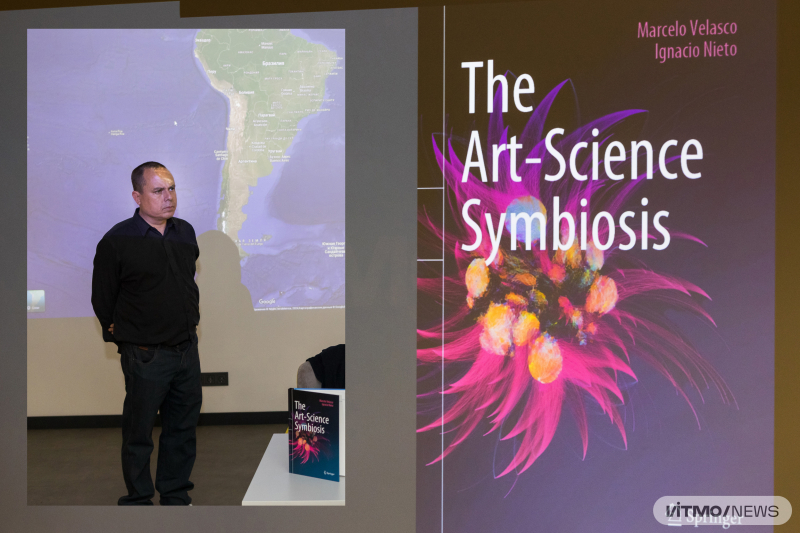

At Marcelo Velasco and Ignacio Nieto’s on-site course at ITMO University. Photo: Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

Every artistic school has its own style and identifying traits, even despite globalization. What is it that makes Chilean science art projects stand out? And which topics do your artists explore?

Chile is a very open country. But we are quite influenced by the USA and Europe, so we still don’t have a proper Chilean school of science art. Perhaps, that is our unique quality – we can take in all the different paths taken by science artists in the US, in Europe, in Russia, or even in Australia, rather than focus on just one thing, as some do. We’re always looking at new ways of thinking and trying to account for our own history and traditions, so that we can offer a new perspective on the world and yet feel at home.

Right now, our artists are especially interested in several subjects. They study our ancestors – the indigenous cultures of Mapuche, Inca, Aztecs, and Maya, among many others, as they existed before Hispanic cultures arrived in Latin America. In their internet, video, and bio art projects, these artists aren’t just trying to preserve this heritage, but also to understand how knowledge of the past can change our thinking and provide a fresh look on modern challenges.

Ecology is also a concern for Chilean artists. Using animals in art is problematic and is frowned upon by the public, so instead, artists turn to various fungi. It’s a compromise of sorts: fungi are living creatures, but not animals, and we can use them to talk about the fascinating nature of Chile and environmental threats. For example, the artist Ivan Navarro has combined art and mycology (the study of fungi – Ed.) in his exhibition Vigilantes, utilizing lab-grown fungi alongside anthropomorphic, scarecrow-like light sculptures. The idea of it was to show that fungi, which are invisible to humans, actually play a major role in preserving the environment, and these scarecrow “observers” protect them.

Here’s another example: the cell biologist and neurobiologist Andro Montoya Riveros, who combined science and graffiti. His knowledge of biology helps him not only teach at the Alberto Hurtado University (Chile), but also depict these fictional creatures and their evolutionary changes on street walls.

And which projects do you personally enjoy?

“Symmetrical” projects – those that are valuable both for science and for art. It’s also important that we explain complex phenomena in simple words and allow viewers to interact with objects. What would you remember better – looking at a photo or personally using an experimental device and then observing changes as they happen? The second option sounds more appealing, but also more complex from an organizational point of view.

One example of such a project is a work by the Latvian-born US mathematician Daina Taimina. She became known for teaching non-euclidean geometry through crocheting – she creates hyperbolic planes out of multi-colored yarn to help students more easily visualize these figures during class.

How did you find out about ITMO University and the ITMO Fellowship program?

Everything we’ve heard about science art in Russia came from Dmitry Bulatov, a prominent Russian artist and art theorist. We interviewed him for our book, The Art-Science Symbiosis, and we also monitor his exhibitions – all in all, he is a prime example of a bioartist for us. Aside from that, we didn’t know much about Russia or ITMO, and this made it more enticing to find out what this country is like, what science art projects you’re developing, and how our approaches differ.

We got an invitation to join ITMO Fellowship and then began to discuss collaborations with our Russian colleagues. We found out that ITMO launched Russia’s first-ever academic bioart lab, where artists work with biological organisms, primarily plants, and study the line between machines and living beings. Together with the team of ITMO's BioArt Lab, we are now studying the vine plant Boquila trifoliolata and how it can imitate other plants with its leaves. It was clear that our interests align, and so we decided to come to Russia.

Read also:

You’ve conducted a three-week course called Practices and Methodologies of Art & Science Projects as part of ITMO’s Art & Science Master's program. What was it about?

We discussed why it’s crucial that scientists and artists communicate and establish a dialog. Researchers are still reluctant to get involved in science art projects because they don’t fully understand how this art could benefit them. Imagine a scientist who is well-versed in black holes and publishes research papers on the subject. But these papers are only read by other niche specialists, not the general audience. Or, conversely, perhaps our scientist has made an interesting speculation about black holes, but not one that would be appropriate for a research paper. How do they share this idea with the public? Here, art could be a conduit through which to familiarize society with complex scientific ideas.

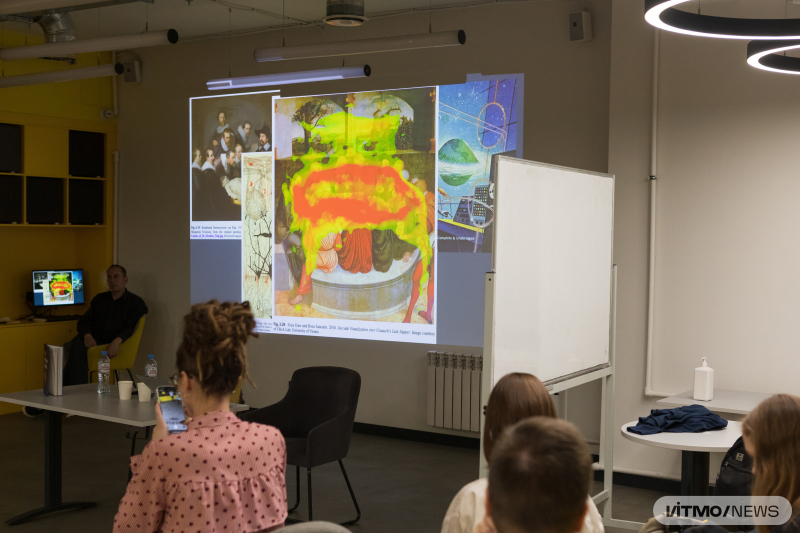

In our course, ITMO Master’s students worked on their projects, discussed them with Chilean students who had taken our course before, and received feedback. We didn’t focus on hypotheses and results; our primary goal was to show that science art is about exploring and communicating new ideas.

At Marcelo Velasco and Ignacio Nieto’s on-site course at ITMO University. Photo: Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

You also collaborated with ITMO’s BioArt Lab on experiments related to your research project Mimetic ability of Boquila trifoliolata. What is so special about this plant and what do you want to achieve?

This plant is only found in our country. In 2014, the Chilean scientist Ernesto Gianoli observed that this vine wraps around other plants and mimics its leaves – taking on the “host’s” color, shape, size, and texture. In this manner, it can evade herbivores. The question is: how does the vine “see” the nearby plants in order to imitate them? Scientists have suggested some explanations, each more outlandish than the other: it senses emissions of other plants in the air, exchanges genetic data with the other plant through microorganisms, or uses photosensitivity and the optical qualities of the epidermal cells within its leaves.

The research continues and we, as science artists, would be really interested in working with this unique organism. Because Ernesto Gianoli conducted his experiments in the field, we decided to reproduce them at ITMO’s BioArt Lab. We will grow a specimen of the plant, monitor the changes in its leaves, and analyze its physiology and genetics. Perhaps, the vine really does have some other way of seeing the world, such as through miniscule eyes located in their leaves. Ernesto Gianoli, whom we’ve spoken to, is skeptical of the idea, but from an artistic point of view it’s interesting to juxtapose the two perspectives – skeptical and philosophical – on the idea that this plant could have special organs of perception that assist in their mimicry.

BioArt Lab has begun growing this vine indoors in St. Petersburg, while in Valparaíso, Carmen Ossa, the head of the Laboratory of Ecology and Evolution in Plants, has built a greenhouse to house several samples. Together with the BioArt Lab, we will conduct experiments in parallel to investigate the phenomena and collaborate on artistic projects.

We are working on how to properly involve scientists in art-science: as a valuable practice in the production of new research ideas, a way to express their subjective points of view, and as a tool to communicate with an audience in a more symmetrical way.