Neurotransmitters and hormones

The abundance of “Love is…” comic strips shows how little we know about love. The only scientifically correct caption for one of them would be “Love is… a dopaminergic goal-directed motivation for the establishment of pair bonds”. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter, or a substance used by brain neurons to communicate with each other. What’s it got to do with love? Let’s learn from the example of monogamous field mice, who are known to be faithful to their life partner.

One distinguishing feature of field mice, or voles, is that they have two types of dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. D2-type receptors are responsible for forming an attachment to another mouse. When a male mouse meets and “falls in love” with a female, its D2 receptors activate and he becomes attached to that specific female. If we were to block those receptors, the male would start attacking females, and if we activated them, he’d fall for the first female mouse he meets. After an attachment has been formed, more D1-type receptors are formed in the male’s brain, which solidifies that relationship by quite literally rewiring the brain. This way, the male mouse’s brain is restructured so as to make sure that he doesn’t fall in love with anyone else. The nucleus accumbens is the same area of the brain that is responsible for addiction to certain drugs, which is why love is often compared to a drug-induced trance. Non-monogamous mice have an increased number of D1 receptors from the get-go and they don’t need to grow new ones, which is why they are able to switch between partners.

The human brain maintains its own serotonin-dopamine balance: the more there is of the former, the less there is of the latter, and vice-versa. Those who take antidepressants (most antidepressants increase the serotonin levels) have a lower dopamine level, which makes them less attracted to their significant other, even if they are in a stable relationship.

In our situation, it’s not dopamine that is at the center of it all, but the hormones vasopressin and oxytocin, which are produced in the brain and then spread through the entire organism via the bloodstream. Using monogamous mice as the model, scientists have found the “faithful gene” RS3 334 in men (the gene is also present in women, but has a different function). That same gene is responsible for the formation of receptors of vasopressin V1a and can turn monogamous mice into polygamous ones. It’s not entirely clear why that happens, but if this gene is activated and more V1a receptors are produced, monogamous mice become polygamous regardless of their number of receptors.

It’s the same with people. A number of curious studies have shown that men with a mutation of that gene are more likely to be unfaithful to their partners. Genetic tests have yet to become commonplace, and thus the results so far have been based on a few Swedish studies with a small sample size of approximately 50 people, so it’s up to you to believe it or not.

Another crucial hormone is oxytocin, which we need to form friendly relationships with others. It doesn’t have to be love, but merely a personal attachment. Some studies have shown that the circumstances of our childhood will affect the production rates of oxytocin and vasopressin. For instance, we know that children who grow up as orphans have a lower vasopressin level. There is even a theory that uses the low vasopressin levels of those who grew up in an orphanage to explain their struggles to socialize as adults.

The Passionate Love Scale

This test includes 15 questions and can be taken on your own or with a partner. In the end, you get an indicator that evaluates your level of passionate love towards the other person. All of the questions in the test, however, are more to do with attachment and desire to spend time together; it’s unclear just how equivalent that is to love.

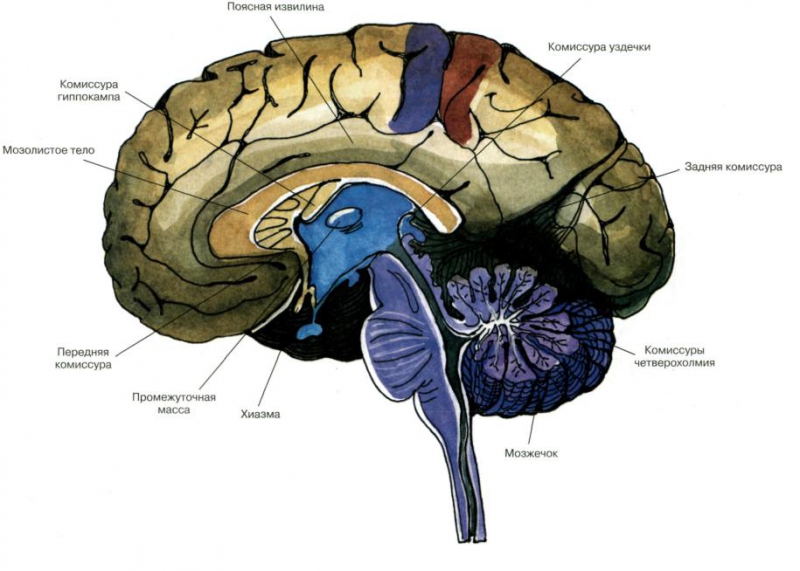

The scale, however, was the first step in the mission to find the brain structures responsible for love. Before that, the only practical results were the ones related to the “faithful gene”, and so the first thing researchers did was follow the psychological maxim of “if you want to measure something, make a test”. It didn’t quite work, so they started to look in the brain and found the nucleus accumbens. Still, there is a direct correlation: the higher you score on the scale, the more activated your nucleus accumbens is.

Functional MRI

After some time, a group of scientists began to study love using brain imaging technologies such as MRI. This method, too, has its limits. There are only so many ways to express love in an MRI scanner without moving around too much. If someone is in love, that feeling is felt 24/7, and you can’t put anyone in an MRI unit for that much time. Therefore most experiments measured brain activity by showing people the image of their romantic interest.

In 2000, Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki tested 17 subjects by showing them pictures of their romantic partner and of a friend who they’ve known for approximately the same amount of time and whose social circumstances are similar. The researchers’ goal was to learn which areas of the brain act differently when viewing the two pictures.

What they learned was that when a person sees a photo of their partner, an area of the brain responsible for memories is activated, and so does the insular lobe responsible for emotions. What this tells us is that, when looking at an image of your romantic partner, you recall the events associated with that person, and these memories carry a massive emotional significance.

Later, they decided to compare romantic love with motherly love, now with a larger sample size. This time around, the subjects were shown photos of their partner and their mother. Even though there are a few areas of the brain that are activated in both cases, some are specific to the motherly kind, like, for instance, the frontal lobes. This means that seeing one’s mother activates not only the areas related to emotional memories but also the logical components that maintain our social relationships.

Another study that employed MRI imaging has shown that, upon seeing a picture of their former partner, people who have gone through a painful break-up will experience activity in the areas of the brain responsible for the sense of physical pain. In other words, seeing a picture of your ex can literally feel like getting punched, and science proved it. MRI imaging, however, is not a perfect method. Scientists will inspect the scans and say that this or that area is active, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the events are equivalent. To make sure that these are not mere coincidences, we need to continue research in this field.

The male and female brain

The hypothalamus is a structure situated deep within the brain, and that’s where the differences between “male” and “female” brains are evident. When we previously spoke about love, we talked about the general sense of attachment formed by neurotransmitters and hormones, and then described it as the activation of certain brain areas at the sight of the loved one. As for the hypothalamus, researchers have attempted to find the regions activated by arousal. For women, it’s the ventromedial cortex, which activates when a woman is ready for sexual intercourse. For men, it’s the medial preoptic area, which is responsible for a general sense of arousal, but evolution has also given them the INAH3 nucleus, whose only function is to produce an erection. Women also have that nucleus, but it’s twice as small and shares the functions of its neighboring nuclei. It has also been found that the INAH3 nuclei are smaller in the brains of homosexual men, which is seen as an indicator of homosexuality being a trait determined by genetics.

What happens after sex?

Before sex, the situation is quite similar for any gender: the limbic system, which controls emotions, is activated along with the areas responsible for tactile sense. After an orgasm, however, the processes in men and women’s brains differ. In men, the activity rate of the amygdala decreases, causing them to become calmer and non-aggressive. In women, the activity rate of their dorsal prefrontal cortex is decreased; that structure is responsible for moral behavior. Women’s orbitofrontal cortex, which is in charge of constantly analyzing one’s surroundings and searching for dangerous stimuli, also becomes less active.

Brain trauma and sexual behavior – what’s the connection?

Behavioral changes most often occur due to damage to the hypothalamus. The thing about the brain is that it’s enclosed within the cranium, and any tumor will exert pressure on the nearby zones, which activates the areas of the brain. A tumor in the temporal lobe may cause a person to have an orgasm when they’re simply walking down the street, all because the tumor provoked the right nucleus.

There are many ways in which this can go bad. In a well-known case, a school teacher had found himself experiencing sexual attraction to his underage students. Upon a visit to a medical specialist, a tumor was found near his frontal and temporal lobes that caused these pedophilic urges (the patient himself remained aware that this was wrong). Once the tumor was removed, the symptoms went away but came back when the tumor grew back, requiring a second surgery. Brain tumors can have a significant effect on sexual behavior because the areas responsible for arousal and love can be activated both by other people and by physical pressure from the growth.

Conclusion

All we can say right now is that, from a scientific point of view, we know nearly nothing about love. The many attempts to explain love with neurotransmitters, hormones, and brain areas have provided us with a lot of data, but does any of it really tell us what love is? The search continues.