From school, we know what parts the brain consists of and what functions it performs. Scientists know much more, but even they don’t claim to understand all principles on which it operates. What makes the brain different from other organs, what roles do lipids play and can their composition be used to tell a wild animal from a domesticated one, or a child from an older person? Read on to find out.

The fattest organ

One well-known fact is that the brain consists of a large number of neurons. There are about 100 billion of them in the brain, and each neuron forms from 1,000 to 10,000 synaptic contacts. But this information isn’t enough to understand the structure and composition of the most surprising and complex human organ.

We know that the brain’s composition includes neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, but we don’t have any idea how many different types all these cells have. Though the brain is a unique object that constantly attracts scientists’ attention, it’s still very underexplored. There are reasons for that. For example, it was only recently that researchers got the tool that allows them to discern between different types of cells not by their electrical activity but by the genes involved.

The brain is a heterogeneously organized organ which has many compartments performing specific functions. How is the brain then different from other organs, like heart and liver, which also have various parts that perform specific tasks? Unlike, for example, the heart, the brain’s compartments have not only different tasks but also a different molecular structure.

As with the majority of organs, 70-80% of the brain is water. But its fundamental difference lies in its protein ratio. There is much less of it in the brain structure than in other organs. At the same time, it has lots of fats. The brain consumes an enormous amount of energy, accounting for about 17% of the body’s energy consumption.

The brain is a very “fat” organ. Lipids constitute more than 60% of the brain’s dry weight and are the material of its cell membranes. That’s why they impact on the quality of all its functions. If the membranes are too rigid, the receptors will work slower, hampering impulse transmission. In its turn, this could disrupt a person’s cerebral and motor activity.

Calculations with lipids

The brain is a dynamic structure which changes in the process of evolution. Scientists can monitor these differences, among other things, based on the changes in the brain’s lipids. For example, they’re able to discern animals and people with different behaviors.

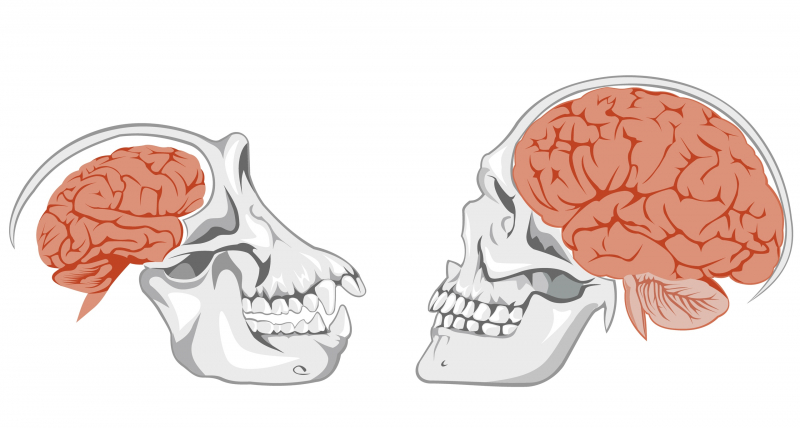

Some eight million years ago humans and chimpanzees had a common ancestor, and even now our DNAs differ by just 1-2%. But is it a lot or a little? Actually, the percentage plays but a secondary role. For instance, within one organism, the liver and the brain have the same DNA, but they still differ significantly from one other. What has more of an impact here are RNA and active genes.

If we look at the lipid map of the human brain and that of a chimpanzee, and compare them using a spectrometer, we’ll see that most differences are concentrated in two areas: white matter and the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for how we think and analyze information.

Another question: are there any differences in the brain’s lipid component between people of different ages? There are, but they’re insignificant. The greatest number of changes in the human brain occurs in the first seven years of life, while there are practically no changes in the 30 to 100 years time period. This, by the way, is good news, because there are lots of theories that the brain wears down throughout the years, like a machine would. Of course, there are neurodegenerative processes taking place (the period of 50-60 years is considered to be the breaking point), but not to a high degree, which is why if we care for our health properly, we can maintain good brain activity up to a very old age.

Apart from that, the differences in the brain’s lipid map allowed scientists to conduct one peculiar experiment. They compared the lipid component in the brains of domesticated and wild animals (on the example of foxes, minks and rats) in order to check whether it changes if an animal’s lifestyle does. It turned out that wild and domestic animals do have a different concentration of lipids in their brains’ prefrontal cortex, which confirmed the hypothesis and also illustrated the natural evolution and “domestication” of humans themselves.