The scientific world, like almost any professional community, is not devoid of gendered stereotypes. When people talk about a scientist, they often imagine a middle-aged man. This is especially evident in the group of natural and technical sciences referred to as STEM – science, technology, engineering, and math. For instance, over the past ten years, 25 men and only one woman – Donna Strickland – have received the Nobel Prize in Physics.

It was therefore decided to organize a separate round table devoted to a discussion on gender diversity in natural and technical sciences at the 5th METANANO conference. Like the rest of the event, the discussion was held online. Five successful women in STEM told their stories, shared their views on gender roles, and proposed ideas on how to support women at the start of their scientific career.

Let's start with a simple handshake

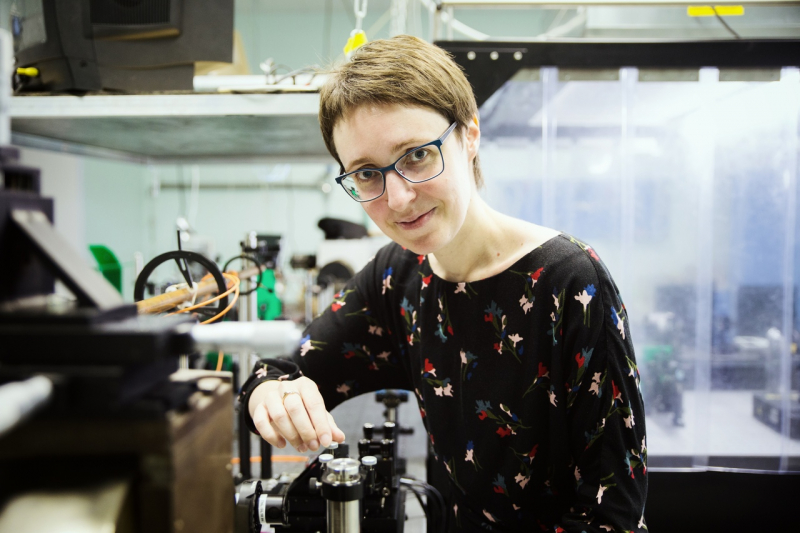

ITMO University graduate Alexandra Kalashnikova represented the Ferroics Physics Laboratory at the Ioffe Institute. She noted that throughout her academic career she has never faced gender discrimination. However, after she returned to Russia from the Netherlands, she understood how women in the Russian scientific community might feel less comfortable than they might in Europe.

“I had the impression that the attitude, the very atmosphere in which a female scientist exists in Russia is worse [than in the Netherlands],” recalls Alexandra Kalashnikova. “While this is not entirely true, this is the impression that you often get. For example, at some scientific meetings, I introduce myself to colleagues and hold out my hand to them to shake. I notice their facial expressions: some are surprised, some are hesitant, and some are interested: "Oh, she wants a handshake." In Russia, it is something unusual when a woman and a man shake hands. But in fact, this is not about the attitude towards me as a scientist, it is something like a cultural tradition. It’s still strong and can make one feel uncomfortable.”

Alexandra Kalashnikova is confident, however, that the situation will change soon. She believes that many of these culturally ingrained customs may disappear in the coming decade.

“I see that younger people are much more open to the world – they travel, have friends all over the world – and have no such problems,” she notes. “I have never experienced anything like that at my lectures. If the lecturer is good, then it is no problem, and no one expects me to be worse than my male colleagues.”

Make diversity a habit

Another presentation was devoted to one of the most painful issues faced by Western universities in the fight for gender diversity. German-Swiss researcher Ann-Katrin Michel, who represented ETH Zurich, addressed the issue of positive discrimination – when some jobs can only be taken by members of a particular minority, in this case, women.

The researcher recalled one of the most notorious cases when such restrictions were introduced. In 2019, the Eindhoven University of Technology, where women make up only about 20% of the faculty staff, announced that it would only accept women for academic positions. If a suitable candidate is not found within six months, men will also be able to send their CVs. The program is temporary and may be revised after the launch. Nevertheless, its introduction caused a stir in the media and the scientific world.

“It's a bit radical,” says Ann-Katrin Michel. However, she stresses that even a small number of positions specifically reserved for female candidates are helping greatly in the struggle to make diversity commonplace in science.

“Why is it important and why should we resort to such measures?,” asks Ann-Katrin Michel. “We need more diversity because it yields good scientific results, which is confirmed by many studies. Take, for example, medical research – heart attacks are very well studied for men, but [their clinical understanding] is less clear for women. A woman can simply die because of a misdiagnosis.”

I was the only person who was interrupted during the discussion

Even though Europe is known as one of the most liberal regions in the world where discrimination is actively fought against, this problem is not a thing of the past. Sylvie Lebrun, a professor at the Institute of Optics of the Paris-Saclay University, said that in 2013 women accounted for only 25% of the total number of researchers in France. In the exact and natural sciences, this percentage is even lower – in 2018, only 22% of lecturers in the physics departments of French universities were women.

This also affects the representation of women in various scientific councils, for example, in dissertation councils. Sylvie Lebrun presented the results of a review of the councils awarding PhD in France. Back in 2011, 60% of the councils studied by researchers did not have women on the board. In 2020, the authors of the review did not find such councils, but still only a little over 20% of councils have three or more women.

As Lebrun admits, during her scientific career, she has not experienced a situation where she would be directly discriminated against because of her gender.

“However, I cannot disregard the fact that physics is an environment dominated by white men in their 40s to 60s,” she says. “I was not discriminated against, but sometimes I suffered from the sexualized remarks of my colleagues. I was often the only woman at a scientific meeting and I was the only person who was interrupted [during the discussion] by men. I tried to concentrate on my topic, but it's difficult under such pressure.”

A lost year reduces competitive ability

As noted by Viktoriia Rutckaia, a postdoc at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, the life of today's young scientists is challenging. A Master's student needs to think about graduate school, people who have received a PhD should look for a postdoc position, and after passing this stage of their career, look for a lecturer position.

The modern competitive environment requires constant monitoring of one’s scientometric indicators – constant publications and reports at conferences are needed. But even this does not guarantee the scientists that they will be able to stay in their university or hometown. Perhaps, they will have to constantly travel and work in different research teams.

“These difficulties exist for everyone, but for women, they are even more serious,” explains Viktoriia Rutckaia. “There are gender barriers, unequal pay, and it is during this difficult period [when it is important to be proactive] that many women want to have a family and children. If a woman loses a year or two [due to childbirth], it spoils her CV and reduces her competitive ability.”

We can tell the world about women's successes

Today, women occupy about 40% of our classrooms, says Daria Kozlova, First Vice Rector of ITMO University. At the same time, the gender ratio in computer science is approximately 45% to 55% in favor of men and 50% to 50% in scientific entrepreneurship programs. However, the First Vice Rector insists, it is too early to talk about the complete overcoming of gender stereotypes because if we look at the gender balance among the leaders of research teams, there is still one woman to nine men.

As Daria Kozlova noted, ITMO University does not plan to resort to positive discrimination or quotas.

“This is definitely not the path that ITMO University will take,” she explains. "But we are going to involve school students, especially girls, in our activities, and we will teach girls to code -– this is our way to get them involved in STEM."

In her opinion, it is important to maintain interest in engineering and the exact sciences in prospective students and scientists and show them that programming, robotics, optics are areas of knowledge in which everyone, not only men but also women, can succeed. It will help shape a future free of gender bias.

“We can communicate with the world and talk about our principles,” notes Daria Kozlova. “We can talk about women's successes in programming or about a female student who won the largest competition in information security. I think we need to bring more interdisciplinarity to the campus so that Science Communication students can work more closely with physics students. I think that in this way we will give a sign to today's schoolgirls that in 2037 there will be more gender diversity among our prospective students.”