You majored in mechatronics. Was it in the school that you decided you want to work with robots?

It so happened that for me, robotics wasn’t that much of a childhood interest. Nevertheless, I had a natural propensity for exact sciences. Especially for computer science and physics: these were my strongest fields. So when the time came for me to apply to a university, I had to decide who I’d most like to be: a programmer or an engineer. In the end, I determined that I probably didn’t want to become a programmer and work with code all the time, though I showed good performance in this field.

Why did you choose ITMO?

I’m from the Russian far east, it was there that I graduated from school. That’s why when it came to applying to universities, I had to enlist the services of a special company that dealt with all matters related to university applications: it’s quite costly to fly from where I was to St. Petersburg. I was offered a choice of several universities I could apply to: Baltic State Technical University, ITMO and a couple of others.

I looked into which majors were offered at ITMO, saw mechatronics and thought, “Wow, that’s cool.” That was what I chose in the end. Having been admitted, I actually visited several other universities, but I found that things were genuinely more interesting at ITMO.

Out of all that you learned at university, what comes in handy in your day-to-day work?

In the course of our studies, what we were getting for the most part was fundamental knowledge. And a number of the subjects I studied did come in handy later on, most of all modeling in SolidWorks, as well as materials science and studies of structural performance of materials. To be precise, what I use in my daily work isn’t knowledge per se, but the understanding of the fundamental principles of working with materials.

Now you work at the company Evapolar, which produces personal portable air conditioners. In 2015, the project’s team launched a campaign on the crowdfunding platform Indiegogo and managed to collect over 100,000 dollars even before the campaign ended. You were one of those who worked on the product from the first prototype to its market launch. How did you join the team?

I was offered to work at Evapolar by Alexey Gordeychik, another ITMO graduate who’d joined the team earlier. He already had a connection to ITMO’s Technopark, where he implemented a range of his projects. We met during his work on one of them, energy-effective display boards for public transport stops. I helped in assembling the boards, and later even designed one of the prototypes. These projects showed good results.

In the summer of 2015, the year that Evapolar launched its crowdfunding campaign, Alexey called me and said: “There’s this project, some modeling needs to be done, come on in.”

Why did you prefer working at a startup to a career at a large company?

I’d already had some experience of working at a large company which I didn’t find all too inspiring. The company was called Granit-7, and it operated under a large design bureau. The work was interesting, we managed to implement a range of engineering projects. There were good specialists working there, a strong engineering team, but the whole structure of the company and the way the processes were conducted didn’t appeal to me very much. I think that it’s hard to find one’s path at a large company: you’re given tasks within a small sector of activity, you do them and that’s it. It’s a far cry from how things are at startups.

First and foremost, there is no structure, no hierarchy at startups: you just come in and do the job. When I joined the team, it only consisted of four people. Back then, we were based at ITMO’s Technopark (known then as QD Business Incubator – Ed. note), which was a sort of a center of attraction. Our founders, Vladimir and Evgeny, authored the idea, it was them who offered to manufacture portable air cons. Alexey, who knows his way around electronics, started making first prototypes, testing the technology, figuring out how the whole thing should work in the first place, thinking about UX and other aspects. I was invited as an engineer who could work out the mechanics part.

What kind of tasks were you solving? What problems did you face and how did you overcome them?

When I was just starting out at the company, I was told that I needed to develop the entire device. But I didn’t have any idea of how I would do this. I didn’t have any significant experience or understanding of the crux of the process at that point, so I had to garner this knowledge on my own.

The simplest thing that could be done in that case was to go to a shop and look at what was on the display, to learn from others’ experience. Just to go into the shop and study a product, for example, a coffee machine, analyze how the cup is fitted in, how the water compartment is made, and why all of these are made in that way. I did exactly that.

Secondly, I had to study up on new technologies of manufacturing and prototyping. And it was great that as soon as we started the development process, we could straightaway test-drive our ideas and prototyping technologies at ITMO’s FabLab, situated on the same premises, the Birzhevaya Line campus. All you needed to do was to descend a couple of floors and there you had it, a laser machine, a 3D printer, devices for casting plastic into silicone, in other words, a heap of different devices, and, most importantly, people who can help you wrap your head around all this.

What made our work more difficult was that there’d been no such thing like our product on the market before and we had to invent many of our solutions from ground zero. Of course, there were general evaporative cooling technologies available, but they were used either in the large-scale industry or were so superficially made that they couldn’t even function properly. We were the first to enter the market with a serious product.

How much time did it take you to come out with your first prototype?

About three months. Our main task then was to create a presentational sample that would perform its main functions, more or less. It was necessary to show people how the technology worked, and to test the main technical solutions, though the majority of them weren’t correct. But I think the prototype did its job well. Later on, we improved the device in a significant way, and I think that we managed to create a good product.

You note that your product now has over 100,000 users. How do you continue working on it now?

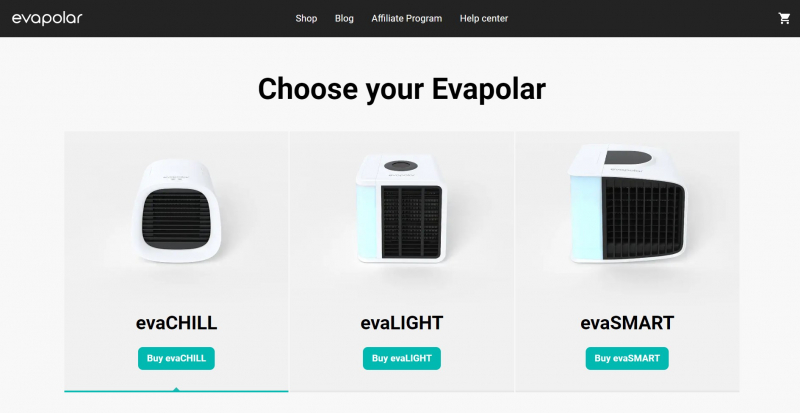

As of now, we offer three products that are based on the same operating principle but have different characteristics: these are evaLIGHT, which was our first product, evaSMART, our second product with smart features, and evaCHILL, our third offering targeting the low-cost market category.

We did a lot of work on design, UX, and other technical aspects that initially posed problems to our device’s operation. Solving these problems, we constantly improved on the assembling process, worked on perfecting the manufacturing technology, and launched all these aspects on a higher level. What I probably consider as our best development is evaCHILL. It is this product, by the way, that yielded us the 2019 Red Dot Award (the judges of this prestigious international design award noted the design and intuitive, user-friendly controls combined in the product – Ed note).

What did working on this project give you personally?

First and foremost, a fundamental understanding of how the development process is run, what main stages it includes, and what key goals need to be set at each stage to proceed in the fastest and most effective way. I wholly grasped the process of creating prototypes by means of the casting method, so it’s much easier now in this regard. Last but not least, I developed a comprehensive understanding of what serial production is like and what key tasks should be solved there.

In your opinion, is it necessary for a modern engineer to not only have a command of technical aspects but also understand the business processes involved?

I think that for general development’s sake, it’s useful to learn beyond your niche specialization. But in practice, I’ve met people who advocate for different approaches. Some don’t take any interest in business processes, they just want to do their job, they take pleasure in that, and that’s normal. But there are people with a different outlook, of which I’m part of. Personally, I’m interested in not only development and manufacturing but also how the market works, how to build business processes, marketing strategy, sales.

Does all this knowledge help you in your specific line of work?

To some degree, yes. In the development process, especially at the early stages when you’re thinking through an idea, you have to understand for whom you are making that product. It allows you to think through its characteristics and create the kind of product that people would find convenient to use.

You have to have some experience of interacting with devices, understand how they’re built, what kind of UX they operate on, what button is located where and how it’s pressed. That is, I can easily press this button, but would it be the same way for a teenager? Our device operates on water, so what volume should the water reservoir be, a liter or three? It’s obvious that no one would carry three liters to and from, but some people want a bigger water compartment, and you have to strike that balance. User-oriented product development isn’t that easy. To consider all the nuances from the very beginning, you need a substantially large experience and range. You can’t make a product that meets the requirements of absolutely everyone, but you need to understand whose requirements it absolutely should meet.

What would you recommend today’s students to pay their attention to while still at university so that it would be easier for them to build a successful career and fulfill their potential?

I consider it very important to obtain work experience while still at university. Student years is a period of life that is largely free from responsibility: you just study, gather knowledge and experience. That’s why it’s crucial to use this time to not only build a solid theoretical background but also focus on the practical side of things. If you want to work in the real world, you need to go outside of the university walls and look around.

Finally, the key step that needs to be taken during your time at university is understanding what exactly you want to do going forward. Many don’t have the answer to this question when graduating from school, but university studies can give you an understanding of where you’re moving and what you want to achieve in life.