How long have you been working here? And what made you choose ITMO?

This is my third year here. Way before I stumbled upon the job offer, I’d already heard that ITMO wasn’t a typical university. I didn’t really know what it meant but was excited to find out. I was impressed when my friend who works at the university said that they have Avengers posters and photos of deans on the walls. Then, I started to picture that there you can break rules and have fun, and I was sold. I’d worked at other state organizations, too, but you don’t normally have much freedom there. So, when I learned more about ITMO, I thought that maybe it was different. And here I am.

How did you feel when you learned you’d won the contest?

I was pleased to receive such an award. Students were given a say in the selection first. They showed an interest in my work and rated it highly. It was mind-blowing to see so many people appreciate my achievements. I also received valuable feedback from my colleagues, and my loved ones supported me throughout the entire contest.

Antonina Fedorova and Valeria Limonova at the Open Education Conference. Photo courtesy of Dmitry Grigoriev, ITMO.NEWS

What else did the contest give you?

I found meaning in my work. It’s demotivating when you can't get along with your students. In spring, I went through burnout and even thought about quitting teaching. This victory was a new turn in my career that gave me a boost to move forward and showed me once again that I’m on the right path.

As a professional psychologist, you prefer to turn to self-reflection and analyze student cases during your classes. How does your background help you in teaching?

I think it comes in really handy. Because I’m a psychologist I like to express emotions and ask about what others feel. I believe that self-reflection and an open dialog help me establish contact with my students, plus show them that I’m not perfect just like them. Students demonstrate better results in a safe and free environment. During classes, we’re all free to speak out if we don't like something, and I appreciate this opportunity. There are indeed courses that can’t do without self-reflection and openness. Let’s take the Emotional Intelligence class. Sometimes, it turns into a group session: I have a brief consultation with a student and then offer others to analyze the situation from their points of view. My students experience the effect of such sessions and often make their own discoveries.

I continue to do research in psychology and pedagogy, so I don’t only focus on practical methods but also try to explain theoretical concepts to my students. Sometimes, we even design psychological experiments together.

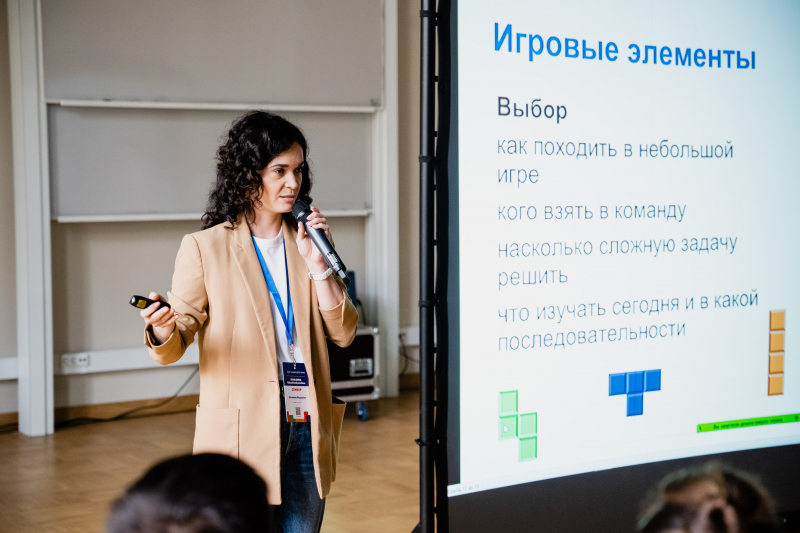

Antonina Fedorova at the Open Education Conference. Photo courtesy of Dmitry Grigoriev, ITMO.NEWS

What helped you build such relationships with your students?

I started to feel differently about students after a few sessions at Yagodnoe. There, I got to know them better. I learned that they are open, smart, and reflective. Now, we enjoy our classes even more: I get more feedback and our dialog goes more smoothly than ever. I wish all teachers could be that open with their students. It’s a game-changer.

Apart from teaching the course on public speaking and presentation techniques at ITMO, you work at the Glagol public speaking studio. What do you like about helping people practice talking in public?

I like that public speaking is a tool that can change our reality. I know for a fact that one person can do a lot with just a five-minute speech. At the studio, we often help speakers who want to introduce new values at their companies – they need to convince people to start thinking differently with just one talk. Naturally, this task can’t be accomplished in one go, but you can at least make people reconsider something. I love such cases because of their focus on global changes and impact.

Antonina Fedorova at the ITMO.OPEN: Educational Practices conference. Credit: ITMO.NEWS

What’s the hardest part of helping someone prepare for public speaking?

That’s a tough question. I think the main challenge is to realize that my expectations from the speech and the speaker’s request can be very different. For instance, I might be thinking of a speech that will knock them dead and the speaker actually wants something more down-to-earth. I try to understand their motivation, but I am often frustrated that I have to do something ordinary. Sometimes I need to remind myself that such regular things are needed too.

You work with both students and adults. Are there any differences in how you approach these audiences?

Not every student understands why public speaking is important, so I have to demonstrate to them that these skills can really come in handy even when they are telling a story or trying to prove their point to a friend. So, these skills aren’t really relevant for students now. With adults it’s different – they need the training here and now, they ask questions, and want feedback.

Learning is a unilateral process and I like to share responsibility for its results. But it depends on the students – sometimes they don’t want to learn and push back. Once I had two students in my course: one of them had boredom written on his face and told me my course was useless for him at the end; the other was really active, asked a lot of questions, and reached out for more feedback – at the end of the course, he told me he’d learned a lot. They both sat in the same classes, but each got something else out of it.

Antonina Fedorova at the ITMO.OPEN: Educational Practices conference. Credit: ITMO.NEWS

What makes a successful speech by your standards?

When after my talk, the audience does what I want. Most talks aim for a specific action from the audience. When I spoke at ITMO.EduStars, I wanted 15 people to follow the QR code link and join a community – and exactly 15 people did that, so I was really pleased.

You also organize the Show of Stories. What is it all about?

My colleague from Glagol came up with the format and hosted the show once in Rostov-on-Don, and then she suggested we organize it in St. Petersburg. At the show, we set a topic and then ten speakers tell their stories about it. We help them prepare their talks following the rules of storytelling, making sure there are conclusions. It’s a show for those who like to perform and have a good time.

What are your other hobbies?

I dance and I am in a book club, where my friends and I read fiction and discuss it. I don’t really like novels because as a psychologist I feel that they are always based on drama and neurotic relationships. For instance, when I was reading Of Human Bondage, I was really irritated with the main character, who couldn’t get out of codependent relationships: everyone dumped him, but he kept loving them. I wanted to get him to talk to a therapist. What I do enjoy are stories of friendships or our society. My latest favorite is Hard to Be a God by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, even though it’s a novel, too. I enjoyed discovering a society’s moral dilemmas and witnessing its transformation. I also have a cat called Mars, who is a very sociable five-year-old.