Ecosystem

The exhibition’s main subject is an examination of ITMO itself and the interspecies, interdisciplinary, and intertechnological interaction within one ecosystem. The event’s curator draws a parallel between the university’s internal framework (with networks of interactions between students, lecturers, scientists, research teams, partners, and external institutions) and the networks that exist in nature, such as mycelium, which connects various species into a singular system, allowing them to exchange nutrition, resources, and signals with each other.

Hence the exhibition’s name – Optomycelium – which underlines the university’s scientific and technological focus and its similarity to a branching system in which research centers, faculties, and individuals possess their own goals and tasks, but are always ready to help each other grow.

Indeed, many of the works were created with the support of ITMO University’s scientists. This was one of the project’s goals – to create a platform where science artists could collaborate with research teams. According to Evgenii Khlopotov, the curator of the exhibition and a student of the Art & Science program, scientists not only took part in developing specific projects, but also took part in the selection process:

“The concept for Optomycelium emerged six months ago when I was in my first year. We were invited to take part in a contest and develop an exhibition about ITMO that could also facilitate collaboration between students, artists, scientists, and laboratories. My concept won and we launched an open call for artists. I asked the authors to think either about the beauty of technologies that ITMO works with or, keeping in mind that technologies don’t exist independent of time, to fantasize about the kind of future – positive or negative – that could result from the development of these technologies. As part of the selection process, we showed the proposed projects to scientists so that they could assess each proposal’s scientific components,” tells us Evgenii Khlopotov.

Evgenii Khlopotov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

This is the first time that ITMO has become a subject of artistic reflection and interpretation. But according to Dimitri Ozerkov, head of the Master’s program and the Contemporary Art Department of the State Hermitage Museum, practically every major organization eventually reaches this point of self-analysis.

“It’s a kind of self-reflection, self-awareness: for any institution, there is a point where it begins to examine itself and wonder: “What am I? What are my limits, my aspirations?” So it is with artists, who also eventually look inwards: how they work, what they do, how they live, with whom they speak. Nevertheless, it’s not about navel-gazing, not in the slightest. It’s more of an attempt to understand how Art & Science can be a part of the existing system of knowledge and the university’s historical structure,” he explains.

Dimitri Ozerkov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

The sound of science

Media artists Ildar Iakubov and Boris Shershenkov, lecturers at the Art & Science program, took on the topic of the university’s self-reflection.

In his work /root_cave, Iakubov turns to key events in ITMO’s history: from Soviet times to the present day. Digital open-source data on the university’s scientific life and its influence on the development of Soviet science was filtered and processed using an array of machine learning algorithms. The result was a neural network-based video tour of the university’s history. Historical analysis of the data was carried out by the artist in collaboration with Mikhail Galperin and Alexander Kudryashov (students of the Data, Culture and Visualization Master’s program) and Alexandra Nenko, Marina Kurilova, and Maria Podkorytova (staff members of ITMO’s Quality of Urban Life Laboratory).

The installation /root_cave. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

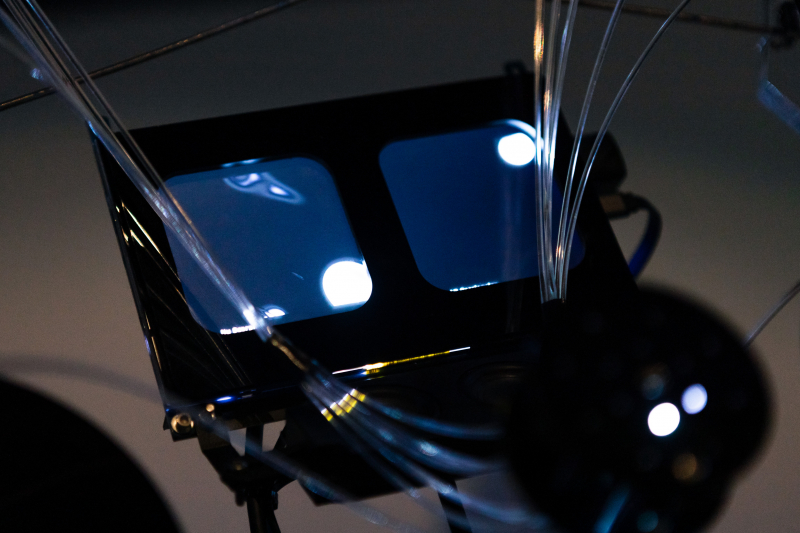

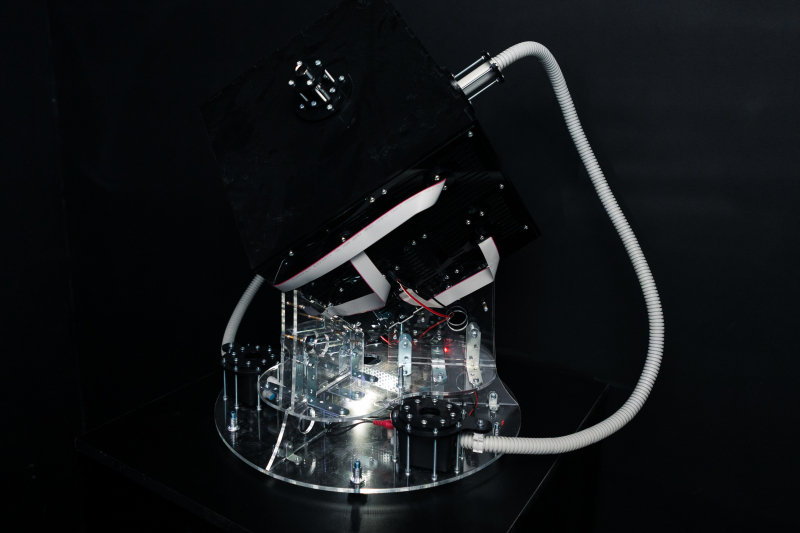

The artist Boris Shershenkov – with support from Maksim Khlopotov, the deputy dean of Information Technologies and Programming Faculty – developed a device called Digitoscope ITMO. The contraption analyzes data on the university’s publications in the Scopus database and converts it into two-dimensional visual structures that reproduce the logic of cellular automata. This visualization demonstrates the origins of “infomolecules” – data that is self-organized into living structures, precursors to virtual post-biological life forms. The accompanying audio, generated from the resulting visuals, lets viewers hear dynamics of academic life that would otherwise be imperceptible.

The project Digitoscope ITMO. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

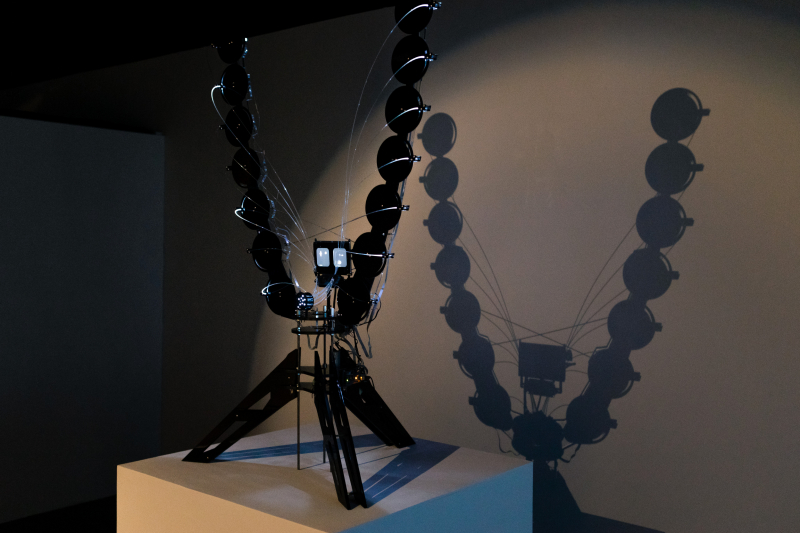

The renowned transdisciplinary artist and researcher ::VTOL:: also decided to visualize and make heard that which cannot be imagined. His project J2000.0 models the movement of stars in two star systems: Nu Scorpii and AR Cassiopeiae. Revolving disks (their number equals that of the stars in the two systems) change their speed according to a mathematical model based on theoretical calculations of gravitational interactions. The infinite audio track, generated by the device’s own mechanism, lets listeners hear the poetry of faraway worlds – physically unreachable, but ones we can travel to in our imagination.

Natural internet

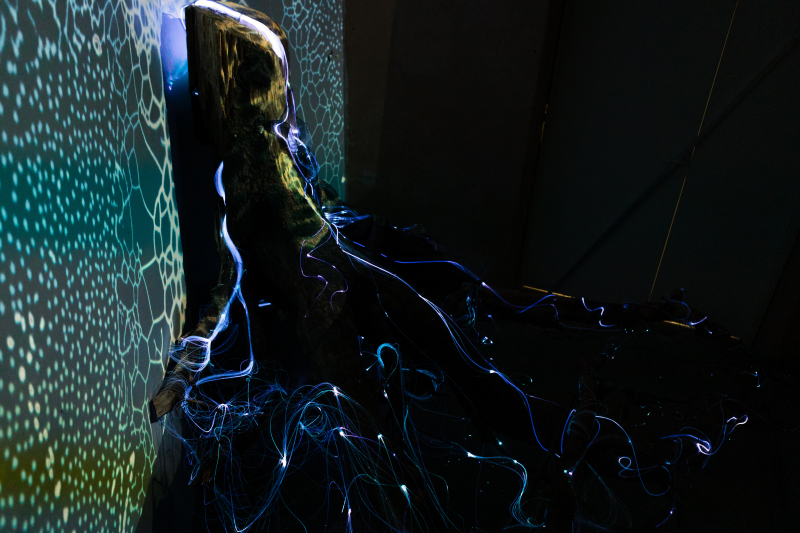

The exhibition’s main premise is the analogy between natural and technological systems that allow us to exchange information and resources, as well as communicate with other species. Like the internet, which connects people to devices and each other, so do natural ecosystems facilitate the transmission of signals. This is demonstrated most clearly by Grigory Kirgizov’s installation Cyberrhiza. The project consists of tree roots, optical fiber, and a video projection generated by software code that simulates a slime mold. According to the author, his project was particularly inspired by SCAMT Institute’s use of bioengineering, biorobotics, and metamaterials.

Cyberrhiza is a clear representation of the main functional principle of ecosystems, in which all participants act based on their interests, but each is connected to others as part of something bigger, be it a mycorrhiza (a symbiotic network formed by fungus and plant roots), the cells of living organisms, neurons in the brain, a human community, or even the global internet network.

“If we look closely, we’ll see that the ways in which living matter is organized are always similar, even if it’s not clear to our mode of thinking. I wanted to show the possibility of synthesizing parallel lines of evolution: natural and technological. I believe that today, it’s especially important to talk about this, as technologies now often turn out to be hostile towards nature. Humans are alienated from nature and technology all at the same time. In my work, which involves a technobiological symbiont and an interface with which to interact with it, I want to overcome that alienation and make the borders more permeable – to consider the idea of symbiosis between living organisms, technologies, and humans,” explains Grigory Kirgizov.

The installation Cyberrhiza. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

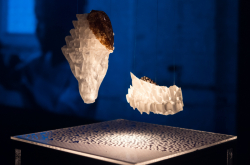

The installation 16.22.CO2 also deals with the topic of connection between humans and nature. Its author, the media artist Anastasia Lukuta, looks towards alternative, inhuman communication systems in order to understand that which lies beyond the limits of understanding. Even though the subject is studied by many scientists and artists, it is still difficult for most people to come to terms with the idea that plants, fungi, animals, and bacteria can communicate with one another. To make it possible for humans to perceive interspecies communication, the artist has constructed an interface based on the exchange of carbon dioxide between a mycelium and a human. The project turns the established anthropocentric concept of plants producing air for humans and other species on its head – for the installation, the artist establishes an opposing narrative in which her breath creates an ideal living environment for an oyster mushroom mycelium.

Environmental disasters and extinct species

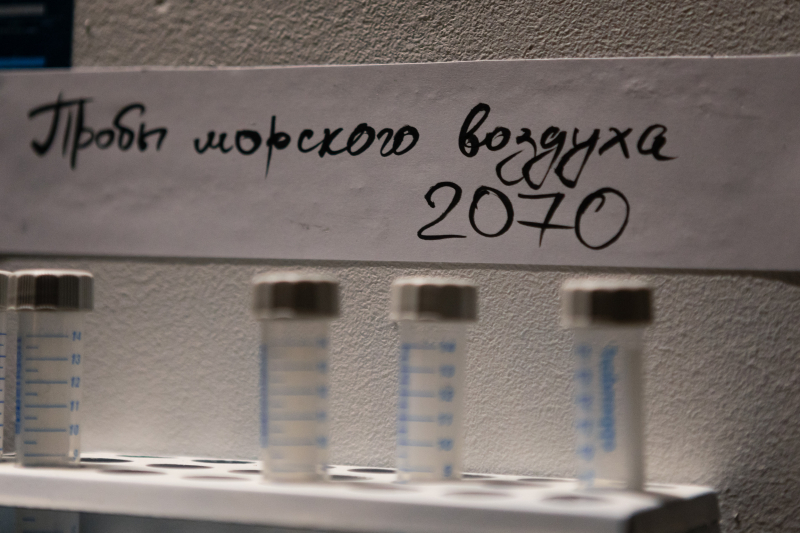

The artist Galina Alferova ponders a new perspective on nature in her installation Мама, смотри, дельфины! (Mom, Look, Dolphins!). The work presents a possible future that could occur if we don’t change our ways anytime soon. It’s 2070 and an environmental disaster has made all marine spaces uninhabitable, poisonous, and dangerous. The air is poisoned, the sea is toxic, and all that’s left is to look back on the old days, sort through old pictures of seaside vacations, and inhale an artificially synthesized aroma of the seas of the 2020s.

The project Mom, Look, Dolphins! Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

“Can we imagine that in just 50 years – when our grandchildren become of age – none of this will be there? There won’t be a sea, no resorts to visit, no air to breathe – all too polluted. You can find out how the sea will smell in 2070 using samples we’ve developed with Svetlana Ulasevich from the Infochemistry Scientific Center based on fish extract, diesel fuel, and algae. According to my artistic study (based on numerous scientific facts), the tentative point of no return would occur in 2047 – by that time, factors such as chemical pollution, ocean oxidation, and growing temperatures will reach critical figures and result in conditions that won’t be adequate for most of marine life. In fact, even today, there are official claims that the sixth mass extinction event has begun and the number of fish has reached a record low,” says Galina Alferova.

The installation Ghost Forest. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO.NEWS

The topic of extinction is continued in a work by Olga Kisseleva, an artist and a professor at the Panthéon-Sorbonne University. Her project Ghost Forest is dedicated to extinct plants recreated by archaeobotanists. Using an ancient palm seed (also shown at the exhibition) found by the author at the Masada fortress in Israel, French biologists have been able to cultivate a date palm that they named Methuselah, some 1,500 years after the plant went extinct. In her work, the artist considers the possibility of recreating an ancient landscape as a way to remedy the damage caused by humanity. Another theme of the work is the exchange of information between “resurrected” plants and present-day ones as a sort of time machine that sends messages from the past to the present and vice versa.

The Optomycelium exhibition is open through February 13 on all days except Mondays. Address: AIR gallery, Birzhevaya Liniya 16. Special art mediations are held on Saturdays and Sundays; to sign up, visit the project’s website. Follow AIR on Instagram (@air.itmo) to find out about future events.