The event brought together leading sociologists of science: Yulia Gryaznova, the head of the Directorate of Strategy, Analytics and Research at National Priorities; Ekaterina Streltsova, the head of the Centre for Statistics and Monitoring of S&T and Innovation at HSE University; Timofey Nestik, the head of the Laboratory for Social and Economic Psychology of the Institute of Psychology of the RAS; and Andrey Kozhanov, the head of the Centre for Student Academic Development at HSE University. Konstantin Fursov, an associate professor at ITMO and the deputy head for research and education at the Polytechnic Museum, moderated the discussion.

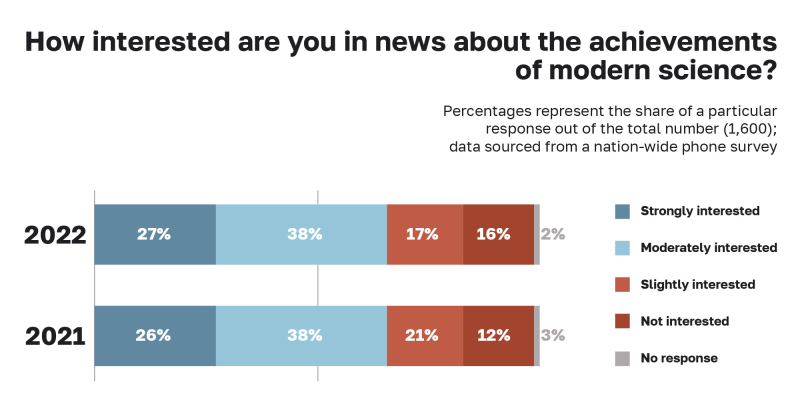

Having reviewed the results of the latest surveys by leading Russian institutions on the public’s interest in science, the speakers outlined the main reasons behind an apparent lack of engagement.

It has nothing to do with me

In January 2023, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center conducted a survey of 1,600 Russian citizens, asking participants if they were interested in scientific and technological advances. 70% of subjects responded positively; however, 58% couldn’t name any actual breakthroughs made in the past few decades.

Yulia Gryaznova believes that these results can be explained by lower engagement with topics that bear no actual relevance to respondents’ lives. Her research group conducted a small experiment with two groups of participants: students from 200 universities and volunteers in a social initiative. Both groups were asked how often they interacted with science-oriented content. Only 19% of students and 22% of volunteers claimed to regularly check relevant news outlets, while 56% and 33%, respectively, said they only did this from time to time.

Next, the researchers tried to look at the roots of this lack of interest: 55% of all respondents stated they were more engaged with other topics, such as art, culture, travel, or self-improvement. Another 40% of participants replied that science has nothing to do with their lives.

The results of the survey of public opinion of scientists and the Russian Academy of Science. Credit: the Russian Academy of Sciences

It’s too complicated

Another insight from this study: scientific articles are hard to comprehend because of their heavy use of specialized vocabulary and complex formulas (as stated by 46% of volunteers and 27% of students).

The next important factor is the field of research. Elizaveta Sheremet, a Master’s graduate of HSE University and a PhD student at Columbia University, shared the results of her study of public trust towards various fields of science based on data from the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (conducted by HSE University since 1994).

The survey’s experts held over 5,000 interviews (primarily among people without a degree – they constituted 76% of respondents). The participants were asked to evaluate the credibility of research in a given field, taking into account the amount of funding and the reputation of the institution. As it transpired, these two factors played a greater role for people without a degree than for university students. Elizaveta Sheremet believes this could be due to the general attitude of skepticism common in academia, which can be adopted by students as they absorb new knowledge. In general, the majority of surveyed Russians are inclined to trust scientists – among the 3,600 respondents in a study by the Institute of Psychology of the AS and Zircon group, 50% trust scientists unconditionally and another 33% are inclined to believe their results.

Photo by ITMO.NEWS

It’s not discussed enough

A survey conducted among students and volunteers by the autonomous non-profit organization National Priorities showed that 40% of respondents from both groups do not consume any science-related content via social and mass media.

A joint study by the Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Zircon Research Group came to a similar conclusion. The study, which surveyed a total of 3,600 Russians by phone and online in August 2022, showed that only 42% of responders occasionally encounter science-related news. The primary source of such news was television (65% of the answers), with online video content coming in second place. Podcasts, radio, and print media proved to be the least popular.

The same study also indicates that people aren’t always familiar with the history of science. As part of the survey, respondents were asked to name the most significant scientific achievements of the past 10 years in various fields: medicine, physics, space exploration, mathematics, chemistry, materials science, and others. They were also asked to name any prominent living Russian scientists. Out of all the respondents, 42% could not recollect a single scientific breakthrough while 84% failed at naming even one scientist.

Photo by ITMO.NEWS

How to make science more appealing

The Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the state nuclear company Rosatom collaborated in September 2022 to survey 3,000 Russian scientists. The respondents were asked about what made them interested in science when they were growing up.

- 94% replied that they watched popular science TV shows and films;

- 92% read sci-fi literature;

- 91% read popular science books and magazines;

- 79% read the biographies of famous scientists;

- 72% were inspired by their teachers;

- 58% have had some experience communicating with scientists;

- 55% took part in science-related extracurricular activities.

These results were further corroborated by an online survey of 2,000 Russians who regularly follow scientific news.

Scientists also were asked about what they thought could help increase the public’s scientific literacy. They spoke in favor of TED-like public lectures and YouTube videos while calling out personal blogs and awards mocking pseudoscience as least effective.

Photo by ITMO.NEWS

Andrey Kozhanov says that making science-related content easier to digest (without dumbing it down) is important to increasing its appeal. He gives the example of two different ways to name the same lecture: Sociology of Deviant Behavior or Sociology of Criminal Behavior. The second option, which features less-obscure phrasing, is likely to attract more interest.

Konstantin Fursov thinks that science communicators are of utmost importance to increasing scientific literacy since they act as mediators between the scientific community and society at large. This role can be fulfilled by the scientists themselves, but also by journalists, teachers, and museum guides. They carefully consider what their audience finds appealing while trying to relay relevant scientific facts as accurately as possible. Depending on the level of scientific literacy, age, and preferred way to consume information, communicators can choose either lectures, videoblogs, or seminars as their format.