How does someone who graduated from the Faculty of Psychology at St. Petersburg State University become a lead analyst at a major company? Have you always had a knack for maths?

I didn’t go to a mathematical school, but I was always interested in maths. I can’t say I was especially gifted in this department, though. As for the Faculty of Psychology, I have to note that this discipline can not only be seen from the classical perspective, but also as a field that studies humans, their emotions, feelings and behavior. There’s also cognitive psychology that is based on mathematics and artificial intelligence. One of the problems it’s trying to solve is describing the human psyche in the language of mathematics. Sometime around the third year of my studies I took interest in this very field, and started studying statistics and machine learning.

It turned out that the knowledge I received at the Faculty of Psychology is a good foundation for working in analytics. It might seem unusual that someone turned to analytics after studying humanities, but it’s quite a normal practice for IT. Even people with a background in social sciences are now rather equipped in the field of applied statistics. And many scientific methods, mathematical models and experiments now enter the humanities, it’s a global trend.

Why did you choose psychology and not a STEM discipline?

I didn’t have a very clear idea of what I wanted to do in life after I’d finished school. Back then, the broad classical program offered at the Faculty of Psychology appealed to me – there was political science, philosophy, statistics, and mathematics. Had I entered the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics, I would have studied maths and only maths from day one, and it was important for me to try my hand in different fields to understand what it was that I wanted to do.

There’s this stereotypical divide between those who study humanities and those who study STEM. Do you think it is an actual divide, or is it just an excuse people use when they are not ready to welcome new ideas?

Obviously, there is a divide because there are people who study literature and like it more than maths, and there are other people who study maths and it attracts them more than literature. The way these people treat this divide is another matter. Some like to say, “I am bad at maths because I study humanities”. It’s a rushed and false conclusion. There’s a mixture between the cause and the consequence: “Why are you bad at maths? Because I study humanities. Okay, why do you study humanities? Because I’m bad at maths.”

Where’s the objective causal link here? Yes, everyone has their own aptitudes towards different activities, but anyone can grasp the basics of maths and use them in their daily life. People often use “I study humanities” as an excuse for not being willing to understand something new. Mathematicians also tend to say they don’t get literature and contemporary art because it’s “those humanities”. I do not subscribe to this view.

Where do you think this dislike for statistics stems from?

Humanities students don’t like statistics because it’s taught in a complicated way. In many universities the social sciences faculties that have mathematics in their program often employ lecturers who work in the area to teach it. For instance, back at the Faculty of Psychology, we learned statistics from a professor at the Faculty of Mechanics and Engineering who spent most of his time with students of his own faculty. That’s where it all originates from: the language that is common knowledge from maths students, is not completely accessible to those who study humanities. Thus, the latter lose all motivation to study a “foreign” discipline. They don’t understand why they need statistics, how to apply it nor what it actually is.

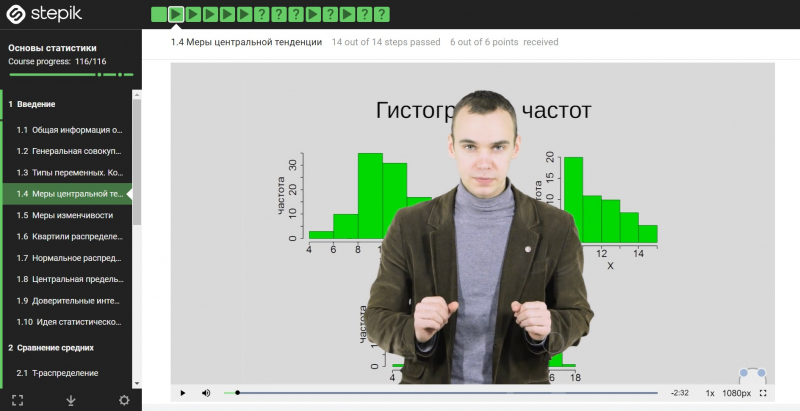

However, I am sure that if we tweak the teaching style a little, making statistics understandable and entertaining with real-life examples, then the students will see that there’s nothing extremely complicated in it, and it can be applied by anyone. My “Fundamentals of Statistics” MOOC on Stepik is living proof. I recorded it for beginners in an accessible way. As of now, over 100,000 people registered for the course. And the most popular review is: “I learned more in three weeks of this course than I did in three years of studying stats at uni. Turns out, it’s not that hard when it’s explained well.”

Why did you create a course in statistics for “non-mathematicians”?

When I was working on the course, I was already teaching statistics at the Bioinformatics Institute but I still didn’t feel very confident. So one of the reasons is a selfish one – I wanted to clear up a few things for myself. That being said, I was mostly driven by creativity.

I quickly realised that I love teaching, explaining complex things to people, and helping them on their career paths. It is one thing, however, to help three fellow students over a break, and completely another to help tens of thousands of people. The realisation that an online course is an opportunity to make a free product for the benefit of many people was one of my main motivations to spend time and effort on this project. The course turned out well, and I couldn’t be happier.

Did you analyse your audience? What do people want to get when they sign up for the course?

There are two major groups of users. The first one is people without any STEM background who want to start a career in data science and analytics. The second one consists of people working in humanities who want to use statistics in their projects. There’s also one small group of people who takes the course out of pure interest for data analysis.

As far as I know, your course is already five years old. Are you planning to update it?

No, I decided to leave everything as it is. I like that I managed to record from the first take, and it is still that popular. I have a hunch that it’s all due to the fact that I was only starting my career in analytics when I was working on the course. When “super-experts” give a course, they often lose touch with reality, and I was only one step ahead of my students back then, it brings us closer. They can relate to my story and reasoning.

The course has stayed relevant and will be useful for a long time because it covers the fundamentals of statistics that had been developed in the middle of the 20th century and are used today. Naturally, new approaches do appear but everything starts with these basics.

Give a couple of examples of how statistics can help us in our daily lives.

In a sense, statistics is a science of probabilities, and almost everything that surrounds us on the daily is a probabilistic event. For example, some might say that the probability of a plane crashing is 50% – it either falls or it doesn’t. It seems logical but only at first glance. To get the real picture we have to count how many planes took flights today – and how many of them crashed. Do half of our planes really crash every day? Evidently not. There’s also a popular opinion that planes are more dangerous than cars, but the actual statistics tell us it’s vice versa. Traffic accidents occur much more often than plane crashes.

These are very simple examples but they demonstrate how fundamentals of probability theory can help us differentiate between a pseudoscientific concept and a proven scientific fact.

Statistics can also protect us by helping us tell apart actually qualified specialists and those manipulating their data. For example, there are people who trust in homeopathy because they battled their cold when they were taking homeopathic medicine. The catch is that an overwhelming majority of people get over a cold by resting and drinking water. Thus, I could simply say that I recovered because I was drinking water.

As an amateur science journalist, I am curious how statistics can help me in my work? Do you think I have to understand it?

A science journalist has to build a bridge between science and society by speaking both the languages of science and the public. Statistics is one of the main tools used by researchers to prove the veracity of their hypotheses. And, in a way, they communicate in the language of maths and statistics. If you master it, you will have partly mastered the language of science – you will navigate data more easily and thus will be able to present it to your readers in a better, more accessible way.

With that said, my answer to your second question might surprise you. No, a science journalist doesn’t have to understand it. Yes, you have to know the absolute basics of statistics to be able to clear some things up with the experts. But there’s no need to have the ability to analyse data, code and know all the intricacies of statistical analysis. Being a good journalist without this knowledge, you can always call me or another specialist and ask them to fact check your text or analyse the veracity of a scientific publication.

What would you recommend to those only starting to learn statistics?

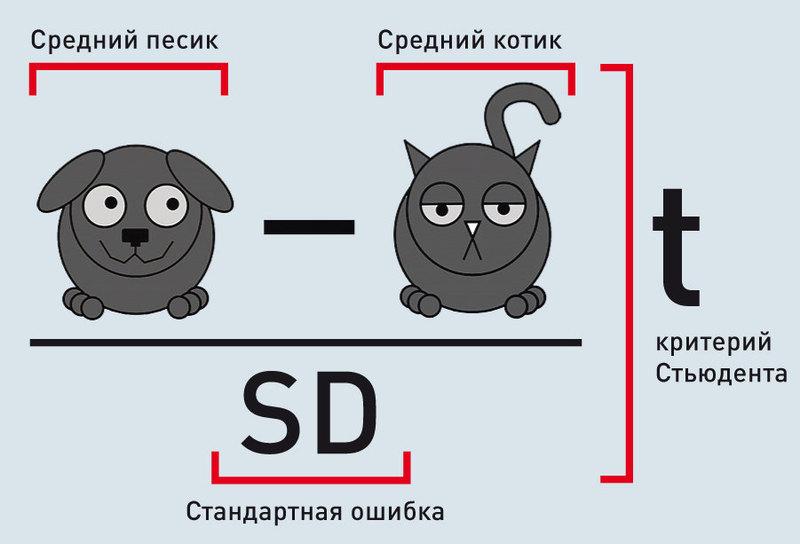

There’s a great book, “Statistics and kittens” (in Russian) by Vladimir Savelyev, another graduate of the Faculty of Psychology, who also wanted to present statistics in a way that everyone can understand. It dawned on him that not many people love maths, but cats are everybody’s favorites. That gave the start to a book teaching statistics with the help of cats.

We’ve mentioned my MOOC “Fundamentals of Statistics” on Stepik a number of times today already. I would like to add that as you take the course it’s better to apply the knowledge you’re getting in your projects. The more practice you get, the better.