AIR.Showcase is a great chance to see art objects created by students as part of workshops hosted by professional artists and science art experts. Works presented at this exhibition were developed during a BioArt course under the supervision of Lyndsey Walsh and Laura Rodriguez. Together with Ms. Walsh, they learned to work with biomaterials and use them to create artistic expressions. The training was held online: the artist supervised the students via Zoom as they worked in a lab.

In total, the exhibition features six projects; their creators strived to reflect on the interaction between human and non-human agents, see the world from a non-human-centric perspective, as well as focus on the ethical and moral issues of animal exploitation.

The gallery’s curator Khristina Ots emphasizes that all works presented at the exhibition create a singular, rather eerie atmosphere despite having been created mainly through individual effort. Such an atmosphere goes hand in hand with the central theme, namely a dialogue with the non-human and, therefore, essentially alien.

“I think it has something to do with students trying to reach the non-human and explore what lab mice feel, how people should treat animals, and whether what is considered dead really is. The artists touch on the dichotomy between the living and the dead, identity and form, ethics and exploitation,” explains Khristina Ots.

ITMO.NEWS visited the exhibition and talked to the authors of the works to learn more about the meanings of their projects, the subjects covered therein, and the difficulties they experienced in working with biomaterials.

Victoria Gopka on the Living Labor project

(Anna Kaplan, Victoria Gopka, Dina Zotova, Natalia Malinina, and Sofia Osbanova; supervisor – Anastasiya Kryuchkova)

The project takes the form of a sphere wrapped in ferromagnetic spider silk. Inside the sphere are two large magnets that make the web shift and pulsate thus creating the effect of a “breathing” living object.

This idea came as a follow-up to a lecture at the SCAMT Lab, where we learned about the spinning process and the life of spiders. We then thought about the alienation of labor; after all, to spiders, webs aren’t just products of their activity; they are an important part of their bodies that they use to communicate, hunt, and defend themselves. So, basically, people steal the fruit of their labor and give nothing in return. However, they provide spiders with food and shelter (eg. plastic boxes). Can this be called symbiosis? And do spiders really care where to live: in a box or among nature?

In our project, we raise a number of questions: is it possible to apply the humanistic approach to labor to non-human species? Can we consider a created biogenic mechanism as meaningless and alienated labor controlled by humans or is it still connected to the spider’s body?

I think that it simply does not interest scientists. The prospects aren't bright on this subject, as clearly, humanity is unlikely to abandon such practices. But we are still trying to draw people’s attention to this issue and hope that they will at least start to care about the animals whose labor they exploit. Even when we talk about saving the planet, we focus on people first and don’t stop to consider the other species.

Natalia Malinina on the Skinless Mouse project

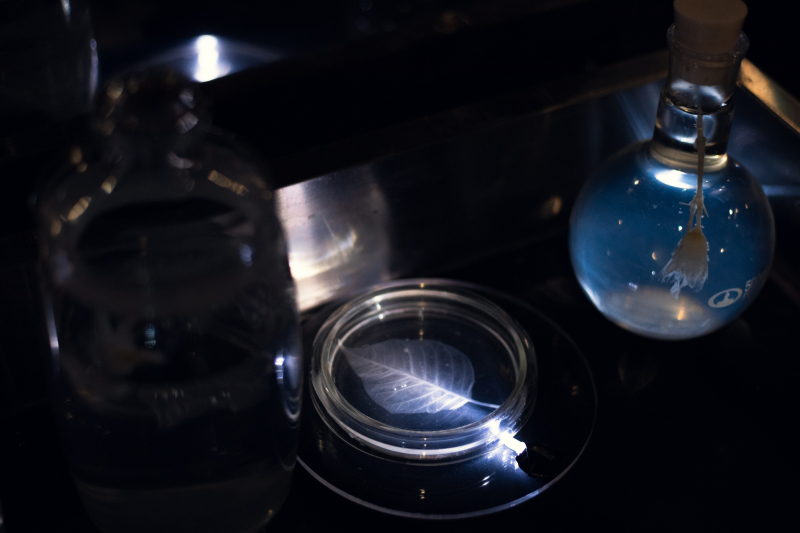

Natalia’s project is a Petri dish containing a decellularized sculpture made of plant tissue. The wire on the body of the sculpture expresses pain, terror, and helplessness – what lab mice experience during invasive scientific experiments.

In fact, this is a prototype of a living sculpture that will be created using cellular engineering technology and will include the C2C12 cell line – myoblasts cultured from the thigh muscle of a mouse back in the 70s.

The mouse that was used to collect these cells died long ago, but its cells continue to live in various labs around the world. We tried to bring these cells back to their original form with the help of a scaffold – a 3D matrix along which cells must grow. This technology is commonly used to grow living tissues for transplantation and scaffolds are 3D printed.

I cut out the shape of a mouse from an apple, then decellularized it or, simply put, removed all the cells, and used the resulting framework to grow cells within a specific structure. Sadly, the experiment was a total failure: the cells simply spread over the Petri dish. That’s why the version on display is a prototype.

This project is devoted to lab animals and their use in science. Most of them are used in horrific experiments: scientists drill their skulls, implant interfaces in their brains, and perform mutilating surgeries on them. Often, these animals are kept alive with open wounds and exposed brains. My work is called Skinless Mouse because the skin is what protects the body from external influences, and animals cannot protect themselves from invasive procedures in laboratories.

My project is an empathic look at lab animals. Although we cannot fully stop animal testing, we should keep in mind that they are still living, defenseless creatures that feel pain and fear. I am not against the use of animals as I understand that there is no other solution. However, I cannot help but be empathic towards living beings that have a mind and can experience emotions.

This idea came to me last year when I visited a research institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences for a lecture on cellular engineering. Their research involves rabbits – animals with a very delicate nervous system and easily-traumatized psyche. There, the researchers break their bones to see how they will grow back together and use them to test transplantation techniques. It's hard enough just to think about all this.

Sofia Osbanova and Anna Kaplan on the Golem project

Our project is based on the myth of the Golem – a narcissistic idea of taking advantage of matter endowed with life. The myths say that only humans can bring meaning and life to clay in order to fulfill some of their needs. In our project, we want to show the opposite: that clay is already endowed with meaning, value, and life of its own.

We studied the bacterial composition of clay particles, and the fact that our samples inevitably contain human bacteria illustrates our idea even better, as we also wanted to demonstrate the link between the formation of humans and matter. As the famous biologist Lynn Margulis said, we are “walking, talking minerals,” and our goal is to show that minerals are living vitalities, too.

We all are passionate about clay and also members of the Grounding project, which, too, focuses on the soil. One of us even has a Bachelor’s degree in geology and soil studies. Perhaps, it is one of the factors that influenced our choice of project.

Dina Zotova on the Bioarch project

I am an architect but now I study microbiology. Once, I attended a workshop during which a lecturer used sodium alginate; that’s when I realized how I can connect the worlds of architecture and microbiology.

My project includes photographs of Petri dishes with bacteria grown from samples taken from three different surfaces: the ground, a computer, and my skin.

For my architectural prototypes, I took inspiration from bacterial and fungal colonies and how they expand. That’s how I came up with sodium alginate sculptures, which were formed using calcium chloride.

The result is a spatial visualization of 2D images – photographs of bacterial cultures. Of course, these are not finished architectural models but rather a reflection on how to make living spaces closer to nature. The sculpture with the samples of bacteria collected from the skin represents a living space, from the computer – a public one, and from the ground – a park area. The idea is to transform the patterns in which the colonies grow into a visual form and use it to design buildings and public spaces. The fact that cells operate according to certain biological rules made me wonder whether they know more than we do.

As an architect, I am interested in bringing architecture and biology closer. I think that using biological features in construction will have a positive impact on humans. I would like to promote this idea further: for example, by introducing more biology-based colors and textures into architecture.

Laura Rodriguez on the Becoming a Plant project

I was inspired by Lyndsey Walsh’s classes on the decellularization of plants. During one of them, we took spinach leaves and removed all cells from them, leaving only proteins. Then, this protein framework can be used as scaffolds to fill them with new cells: mouse cells, human cells, etc. It is a quite new yet promising technology. Potentially, it can be used to create implants for circulatory systems. Scientists already can grow cells on surfaces but it is still hard to do so inside a structure. However, numerous scientific articles prove that it is possible.

I would call my project speculative as it demonstrates an attempt to implant decellularized leaf structures into the human body.

The main concept is based on several key questions: what is form and how does it relate to identity? And what happens if we remove content from this form? Let’s say we have a transparent flower, and when you look at it, you continue to see it as a flower because of its shape. But in reality, it is no longer a plant: it has no plan cells, it is just an empty form. What will happen if we place human cells into this flower? Will it still be a flower or will it become a human? And what if we implant a plant under human skin, will we then become plants?

This is both an installation and an experiment. It includes a manual on how to take care of your new implants, including a ritual for gaining a new identity. For example, you should stay hydrated and once a day stand and face the sun. In fact, it applies to any transformative process such as changing your career, moving to a new place, or gaining a new social status.

Those who would like to immerse themselves even more in the world of BioArt have the chance to attend the program’s open events before February 21.

On February 10, there will be a meeting with Lyndsey Walsh, a bioartist and a graduate of the legendary SymbioticA laboratory, during which she will introduce participants to the exhibition’s biological practices and philosophical concepts.

The Open Day for the Master’s Program in Art & Science will take place on February 13 for those wishing to become Art & Science experts. There, you will learn everything about the program and even talk with the program’s curators. The event will also be held online.

And on Valentine's Day, there will be a DNA tasting workshop by Laura Rodriguez. It’s a great chance to try your hand at molecular experiments.