Regular glass can be made more functional with an additional metal layer. This way, it’s possible to create elements for electronics, as well as mark or decorate glass items. However, glass is fragile and sensitive to temperature changes, which complicates the process.

One of the simplest and most flexible methods for transferring metals onto glass is laser-induced backward transfer (LIBT). With it, it’s possible to create micro-level resolution coatings at scales smaller than the thickness of a human hair. In this process, an intense laser beam is directed onto a metal plate, heating the material up to high temperatures and thus causing its evaporation. This forms a cloud of vapor, droplets, and fine metal particles in the air called a vapor-gas plume. The vapor-gas plume then “travels” to a nearby transparent substrate (in our case, glass) and deposits onto it.

“Laser-induced backward transfer has a number of advantages over other transfer methods. It’s a one-step process that requires less energy and doesn’t call for any special preparation of the substrate. With it, it’s possible to precisely and locally transfer metal onto transparent substrates with minimal heat. In our previous works, we’ve already demonstrated its versatility in experiments with various metals and compositions; we’ve successfully applied the method to create protective marks on glass, produce coatings, and ablate nanoparticles that increase the sensitivity of sensor and optical systems,” explains Alejandro Ramos-Velazquez, one of the paper’s authors and a PhD student at ITMO’s Institute of Laser Technologies.

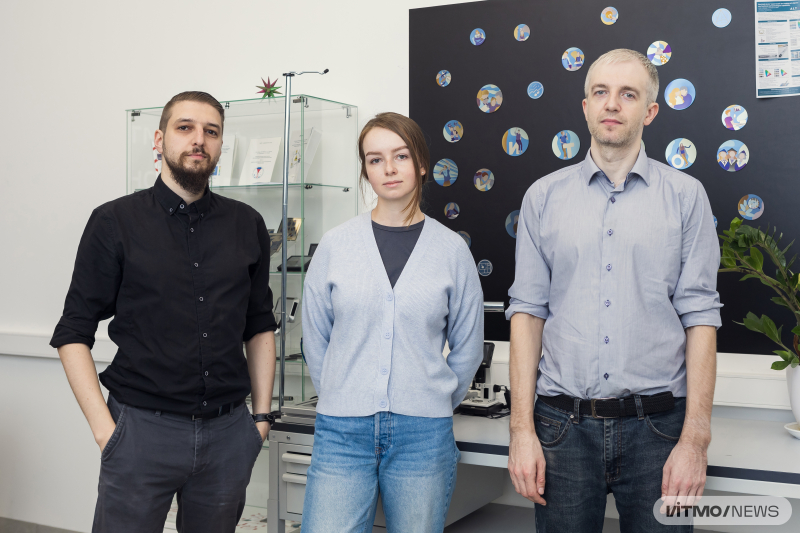

The researchers behind the study (left to right): Dmitry Sinev, Kseniia Arbuzova, Dmitry Polyakov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO NEWS

The main challenge in implementing LIBT is selecting the correct gap size between the metal target and the substrate. Otherwise, the vapor-gas plume may fail to reach the substrate or settle back onto the target. Until now, the method has been studied mostly experimentally, so the gap was chosen “blindly” and many physical effects remained unexplained.

A group of scientists from ITMO, headed by Prof. Vadim Veiko, has solved this problem with a physical and mathematical model that recreates the LIBT process in detail. It can be used to calculate the optimal size of the gap between the target and the substrate, the diameter of the metal ablation area, and the thickness of the precipitation. In order to perform the calculations, the laser pulse parameters, the spot diameter where the radiation is focused, and the optical and thermophysical properties of the metal need to be input into the developed system of equations.

“Thanks to the model, we were able to describe the general physical patterns of metal ablation and explain why there is an optimal range of gap thickness for successful transfer. This is important because the more the flume expands, the lower is the pressure and density of the vapor. If the substrate is placed too far from the target, an air gap remains between it and the vapor-gas plume because the plume’s pressure is insufficient to push the air out to the periphery. As a result, metal vapors do not reach the surface of the substrate. On the other hand, if the gap is too small, it quickly fills with vapor, causing the pressure to rise, and the vapor approaches saturation (at the temperature corresponding to the current temperature of the target surface), which slows down the evaporation process. Additionally, when the gap is small, the vapor density is almost uniformly distributed across the gap thickness, causing the metal to deposit equally on the receiving substrate and back onto the target. Altogether, this leads to less efficient ablations at small gap sizes,” says Dmitry Polyakov, one of the paper’s authors and an associate professor at ITMO’s Institute of Laser Technologies.

Dmitry Polyakov. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev / ITMO NEWS

The new model’s efficiency has been demonstrated experimentally by a team of young researchers from the Institute of Laser Technologies: PhD student Alejandro Ramos-Velazquez and Master’s students Kseniia Arbuzova and Vera Domakova. Variations between the data acquired in practice at low energy densities and that provided by the model were 5-10%. Vera Domakova also adds that with high-speed photography of LIBT, it was possible to capture the dimensional structure of vapor-gas plumes.

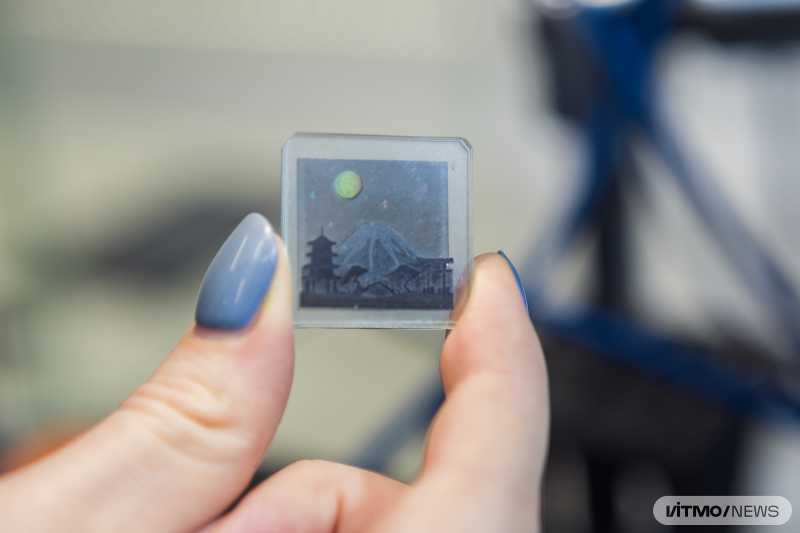

Thanks to the new model, it will be possible to find the optimal LIBT parameters faster and calculate them in advance, instead of having to “manually” select them during experiments. This opens up opportunities for controlled creation of colored metal micron-resolution coatings on glass. For instance, this could be used as non-erasable anti-counterfeit markings. Such markings are usually placed on the packaging, but thanks to the new model, it will be possible to etch them into a product’s material directly. Moreover, the method can be used for decorating glass objects and creating modern art items – a series of those in a Japanese-inspired style were already created by ITMO scientists.

Another possible application of LIBT is transferring metal onto plastic; however, this issue hasn’t been studied yet. Dmitry Sinev, one of the paper’s authors and an associate professor at ITMO’s Institute of Laser Technologies, adds that the research team plans to study the possibility of creating functional surfaces on glass. Such elements can be used as components in optoelectronics and photonics. Another interesting avenue of research is working with new metals; for now, the team has tested steel, aluminum, titanium, and brass. The first two metals turned out to be unusable for the purpose, while the second pair produced the right results: a colored coating and a high level of adhesion to glass.

This study was supported by Russian Science Foundation grant No. 24-79-10230.