What is an infection?

A couple of things should be clarified before we discuss this topic.

Firstly, an infection begins the moment a pathogen enters the body.

Secondly, our immune system must react to the pathogen. If there is no reaction, there’s no disease. A person may carry the infection without being ill themselves: that’s called asymptomatic carriage.

Interestingly enough, bacteria aren’t interested in killing us. For them we’re just feeding areas, vehicles, carriers, and spreaders of their genetic material. They need to eat, reproduce, and invade new territories like any other biological species. The death of a carrier is disadvantageous for any pathogen. Someone who is ill but still goes to work is the best option for them.

Spoiler alert: it isn’t bacteria nor a virus that kills us – our immunity does. Sometimes the reaction of the immune system is so powerful that our bodies just can’t deal with that.

Infection mechanism

The mechanism of infection includes three steps. First, an infection enters the organism and stays there for some time. Then it spreads through any liquids that leave the body. For some time it can exist outside the body: maybe briefly, maybe for a longer time.

Viruses greatly depend on the cells they live and reproduce in: they die quickly outside of them. Meanwhile, some other bacteria, for instance, those that cause Siberian plague, can remain in the ground for decades.

The third step is the implementation of a pathogen into the body, and then the cycle repeats itself. Sometimes, though not often, a pathogen enters the carrier again – that’s called re-infection.

Transmission

Everyone has heard something about airborne transmission, however, few are aware that this term actually includes two different transmission ways.

Air is considered to be the main way of contamination, but it’s actually not the most effective one: transmission through droplet nuclei is much more dangerous, because its tiny parts can stay in the environment for a long time independently. Sometimes these droplets can stay in the moving air up to an hour.

Plus, they can remain on the objects we touch: on money, door handles, and handrails in transport. That’s how we get ill most of the time.

Disease can also be transmitted through dust. It’s mostly used by pathogens that aren’t scared of changing the location. Siberian plague can transform into a spore and stay in the ground up to a hundred years. If its spores appear on the surface, they can be spread by the wind and contaminate anything in the radius of hundreds of kilometers.

In addition, there are other ways of transmission. For example, the transmissible way (used by infectious diseases that are transmitted by animals or bloodsucking insects), contact transmission (requires direct contact with the skin or mucous membranes), blood transmission (infection occurs through contact with blood, for example, during medical procedures), fecal-oral transmission (most often concerns diseases of the gastrointestinal tract).

Outbreak, epidemic, pandemic

Most often, epidemiological diseases appear sporadically. Usually there are small groups of diseased people. An outbreak happens when an illness is spread in a small limited community: kindergarten or school, for example. An outbreak is an agreed term, almost the same thing as an epidemic.

What does it mean when they say that an alert threshold was reached? That means that a certain region was monitored, statistical data on all the diseases that are active in this region was collected, and the average number of ill people was calculated. When this number gets higher than average, it’s called an outbreak, or an epidemic.

Epidemic means that the disease leaves a certain community and spreads among a town, region, or country.

Pandemic is another agreed term. If a disease spreads among the population across several countries in various world regions, it’s called a pandemic.

Declaration of a pandemic is a prerogative of WHO. According to its description, this is the sixth phase of infection spread.

Not all infections can potentially lead to a pandemic: this fact has served us well. For example, scarlet fever was destroyed by antibiotics, and it doesn’t have a pandemic potential. To catch it, one must be in a tight contact with a carrier: that can happen in a kindergarten or school, for instance. Streptococcus that causes scarlet fever doesn’t travel far.

Quarantine or restrictive measures

Quarantine is a term that appeared during the black plague epidemic of the 14th century. This word derives from italian phrase “quaranta giorni”, which means “forty days”. At the time, there was a law for all arriving ships to stay at the harbor for 40 days before the crew could leave it.

Today, everyone is talking about the quarantine as related to coronavirus, but actually the thing that is going on in Europe and Russia is called restrictive measures.

The difference is the following: a quarantine means complete isolation of an outbreak location. That’s what they did in Wuhan, China. The city is closed by the troops, surrounded by a wall, and you can’t leave it or enter it.

At the moment, only two measures have been taken in Russia: intensified medical supervision and observation. Observation means that potentially infected people can’t travel; however, until the hospitals and the cities are completely closed, it can’t be called a quarantine.

Major epidemics

The first thing that comes to mind is, of course, plague. There were two plague outbreaks: the first one took place in the sixth century and was called the Plague of Justinian. The disease earned its name from Justinian, the ruler of the Byzantine Empire at the time. In thirty years, a quarter of the population was lost to it.

The second plague, also known as Black Death, occured in the 14th century, destroyed 60% of the world population, and almost all of Europe. Interestingly enough, it first appeared in Eastern China, from where the warriors of the Golden Horde spread it worldwide in the course of conquering. The initial source was ground squirrels and other rodents from the Gobi desert.

Plague still exists in several regions of China, South-Eastern Asia, and Africa. It’s a natural focal infection that can only be destroyed by destroying all animal species in the outbreak area. The only thing that is done today in order to prevent plague epidemic is disease surveillance. For example, there’s a anti-plague station in Astrakhan, Russia.

In the 19th century the whole world was suffering from cholera: it occured in 1816 in Bangladesh, and spread by British troops among the British colonies and then the whole world. By the middle of the century it got to Russia, America, and Canada. During the century it killed around ten million people. The last time cholera pandemic was declared in 1962, however, sporadic cases sometimes still appear.

Smallpox has been known since ancient times. It’s a highly contagious infection with a mortality rate of more than 40%. In 1928, due to widespread vaccinations it stopped threatening humankind. However, before that, it killed up to 400 millions of people in the 20th century.

Flu once also caused mass deaths. Spanish flu appeared at the end of the First World War and was spread quickly along with the movement of the troops. Around 600 million people got infected, that’s almost a third of the entire population back then. According to different sources, around 60-100 millions of people died.

Coronaviruses

You’ll be surprised, but every modern human not only had a coronavirus at some point, but also catches it almost every year. The thing is, coronaviruses are about 10-15% of all acute viral respiratory infections. We got them from animals, but now they have completely adapted, and coexist with humans perfectly.

However, new forms of flu that are quite similar to each other but still differ from the ones we’ve got used to are quite hard for people to deal with.

At the moment we are aware about three new coronavirus outbreaks.

The first one is SARS-CoV, a severe respiratory syndrome, the causative agent of SARS, which arose in China in 2002-2003. Now we know that it got transmitted to humans through civet cats that were often consumed as food in China.

This was the first animal coronavirus outbreak, and its mortality was very high – 10.5%. However, for unknown reasons, this virus simply disappeared after eight months, but 800 people had died from it, and nearly 8,500 were infected.

The second outbreak is still in action. It’s related to MERS-CoV, the Middle East respiratory syndrome. It varies a lot from SARS both in terms of its features and the mortality rate, which is much higher – 29%. To a certain extent, we’re lucky, because it didn’t spread worldwide: it affected the Middle East and South Korea. Cases of infection still can be detected sometimes, but it doesn’t spread.

The third outbreak is happening right now. SARS-CoV-2 is very similar to the first coronavirus as it also causes pneumonia: that’s the cause of the deaths.

Right now we’re observing the birth of a new disease that will concern everyone, and won’t go anywhere soon. Previously we could only guess how it happened, but today we have a hands-on example. In a sense, it’s an opportunity for the scientists to study the process carefully.

The source of the new virus is considered to be a bat. It was determined by genome sequencing. There’s a 86% similarity with viruses carried by pangolins.

Probably everyone will get through coronavirus at some point, but the mortality rate will inevitably decrease: a process of embedding is happening right now.

It should also be noted that the more powerful an infection is, the less are its chances to stay. Viruses evolve, and the strains that kill get destroyed as well, because their carriers disappear. That’s why any development of a virus gets slower with time: it wins if we go to work while being unwell. So, over time, SARS-CoV-2 will become a usual virus that we get infected with every year.

Risk groups

Coronavirus affects mostly elders. What distinguishes it from the flu is that the latteri affects children under five years and adults older than 65 years. Children often get infected with coronavirus asymptomatically, and that makes them dangerous carriers.

It’s interesting to see how this virus enters our body. It’s very similar to the first SARS, the infection mechanism of which is well researched. It’s related to a substance called angiotensin. People with hypertension are familiar with that as they take angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE).

The virus clings to the ACE-II. To penetrate the cell, it needs to lose its tip, and that’s what serine protease is for.

It turns out that with the age gene expression that is responsible for the synthesis of these ferments gets bigger, especially on the other side of lung cells. So, the lungs become the most vulnerable place for the virus to get in. This also explains why pneumonia occurs, especially in the case of older people: they have more places for the virus to enter than young people.

People who have chronic hypertension are also at risk due to the medication they get.

It’s surprising that children younger than nine don’t get pneumonia, and there are no deaths at all. The mortality rate starts to grow with people older than 50 years, and does so exponentially.

Men get infected almost twice as often as women. No one knows why, it’s pure statistics.

Pre-existing diseases that increase the possibility of fatal outcome are the following: chronic heart failure – mortality of 13.2%, regardless of age; diabetes mellitus with hypoglycemia and no medication – mortality rate of 9.2%; hypertension – 8.4%; chronic lung diseases – 8%; oncology – 7.6%, especially during the chemotherapy.

Is there a cure?

Coronaviruses have a very complex mechanism of getting inside a cell that includes various structures.

Today there are medications that affect serine protease, and they are actively researched, but it will take a lot of time. The development of the medicine will require at least half a year.

However, we know how to save people. For example, it helps to switch the diseased to artificial ventilation, or, even better, to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine. Pneumonia affects lungs, a diseased person can’t breathe, and oxygen levels in blood drop down. Two needles are required for it, one goes into an artery, the other one into a vein. Venous blood goes through an external oxygenator, gets filled with oxygen, loses carbon dioxide, and returns to the arterial bed. The problem is, it’s a very expensive procedure: €12,000 per day for one person.

The spread of infection: what to expect?

Measures that were taken in China would be impossible in any other country: in China they managed to isolate the city completely, erect a wall around it and not let anyone out. It's hard to imagine something like that in Russia. Almost nine thousand epidemiologists worked in Wuhan, and they were able to deploy field isolators very quickly. Our army and the Ministry of Emergency Situations do have the same technologies, but will it be possible to apply them as quickly if required?

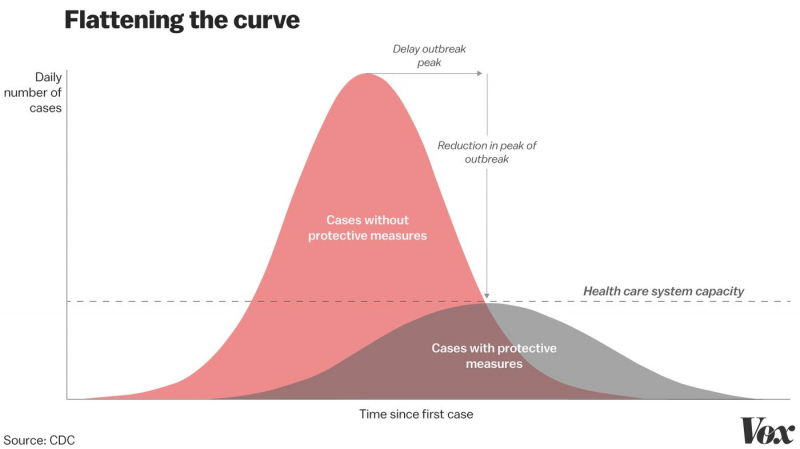

Another problem that occured, for example, in Italy, is the lack of hospital beds. No hospital can handle huge amounts of patients simultaneously. So, the current situation has already shown us that the world is not ready for a real epidemic with a high mortality rate. Serious measures must be taken so that the next outbreak wouldn’t be even more deadly.

The whole lecture is available here (in Russian).

We also have some illustrated tips for you. Please follow the recommendations and take care of yourself!