Could you tell us a little bit about yourself? How did your career in academia begin?

I grew up in Texas and moved to New York to attend college. Then I went to the Graduate Center at the City University of New York where I started my doctoral studies in narrative theory, focusing on the literary works of Vladimir Nabokov.

Why did you choose this particular author?

That’s a tough question. The first book written by Nabokov that I read was Bend Sinister – not one of his best-known pieces. I think I liked it because Nabokov is a writer for writers. He understood the process of creation very well. His writing is allusive, not strictly literal. It’s like a puzzle. As a writer myself, this is what got me interested in his work.

However, later you moved into the fields of biology and the theory of evolution. How did it happen?

Oh, it's a long story. I owe this to Nabokov, too. It’s well known that he wasn’t just a talented author with a good sense of humor. He was also a lepidopterist, interested in the theory of evolution, and in the evolution of butterflies in particular. He had an intuitive understanding of the process of speciation. This is what led me into the sciences. I never imagined that this would happen when I started my literary studies. I became a visiting researcher at the Santa Fe Institute to work on complex systems theory, self-organization, and theories of evolution. My dissertation dealt with insect mimicry. Now I work in an interdisciplinary field called biosemiotics that combines my interests in science and language. That’s why I was so happy to be part of the Digital Humanities Center at ITMO University – interdisciplinary research is the norm here.

“I was pleasantly surprised to see so many women at the university working in science-related fields”

What led you to ITMO University?

Oh, it was a series of coincidences. Many scientists who are prominent in the fields of studies I’m interested in happen to be Russian. As I did research on some topic, or on some theory, names of Russian researchers kept coming up. So I ended up being familiar with many Russian researchers.

A little over eighteen months ago, I applied to the Fulbright Program, and they offered to send me to Russia. I found information about ITMO and the DH Center and I thought I would fit in.

However, you came here quite recently, in February of 2020. What was your first impression of ITMO University?

To be honest, I didn’t know what to expect. I was ready for anything. The first thing that surprised me is that many of my students are from countries other than Russia. Such diversity was unexpected.

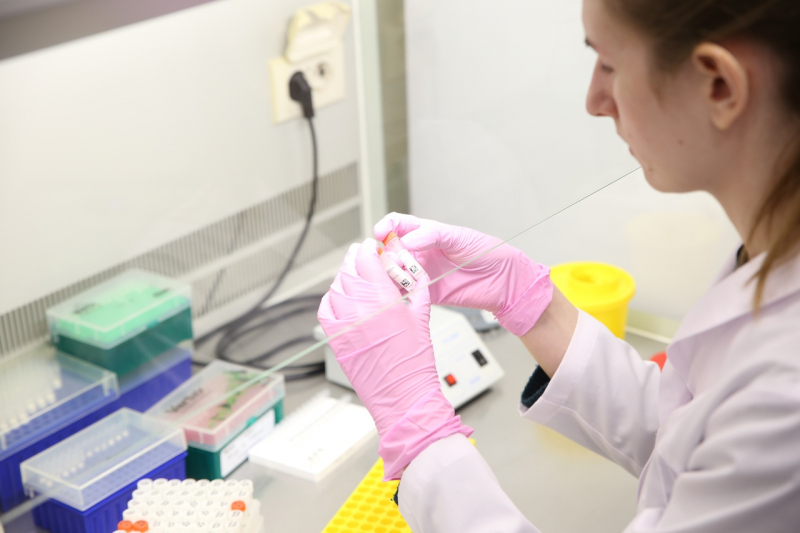

Then, I was glad to see so many women at the university working in science-related fields. It’s a new experience for me and a pleasant surprise. At American and even at a number of European universities, science tends to be dominated by men.

What can you tell us about your students?

I was very impressed by how ready they are to accept any kind of challenge, and to do the research on the very diverse and unusual subjects included in the course. They bring their own experiences and interests to the table. They readily communicate, both with me and with each other. It really inspires me.

You’ve mentioned your course on quantitative and qualitative methods. Could you explain what the classes are about?

Quantitative methods, as a rule, involve taking measurements and counting things. For example, when you research a phenomenon, a type of group behavior, you take the statistical data and come to conclusions based on the data. Qualitative methods are more about applying various other techniques, for example, interviewing subjects and interpreting their responses. It’s not hard to see that hard sciences are more about quantitative methods and humanities are more about the qualitative.

Some people may think that humanities are less objective than the hard sciences, as with the former you depend more on interpretation. However, I wouldn’t put one method above another, or one field of study above another. In class we explore the questions: “What is interpretation? Are there qualitative aspects in quantitative methods? How do we approach truth, whether through qualitative or quantitative methods?”.

Generally speaking, I believe that people, regardless of their occupations, should be interested in what is happening in the sciences. I think the distinction between quantitative and qualitative approaches is somewhat of a false distinction. In class we have been talking about the way complex systems science seeks to discover relatively objective mathematical descriptions of the qualities involved in, for example, group behavior, emergent phenomena, and evolutionary processes. It’s very important to use both quantitative and qualitative methods for a better understanding of the processes that take place in our personal lives, in politics, in art and in society. Ultimately, I’m teaching a critical thinking skills course.

Other than teaching, you’re also working on a project related to Nabokov’s legacy. Could you tell us a bit more?

Nabokov had a theory of insect mimicry, specifically butterfly mimicry. For example, he thought, contrary to popular opinion, that the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and the viceroy butterfly (Limenitis archippus) are not mimics but only lookalikes. He thought that natural selection was unnecessary to explain why some butterflies look like other butterflies. He didn’t deny natural selection had gradually shaped some organisms, but he thought that the similarity between some butterflies was quite likely to arise by chance due to the physical processes that limit butterfly wing patterns. Moreover, he believed that new patterns could appear suddenly, possibly in one or two generations, not gradually as per the theory of natural selection. Nabokov was a creator himself and he realized how the creative process often relies on chance similarities, which may look like a miracle if you don’t understand the physical mechanisms underlying the processes.

The processes that lead to the formation of butterfly wing patterns are well described. Several scientists have conducted research on the chemical processes that determine them. Anna Popova, a Master’s student at ITMO University, and I would like to test Nabokov’s hypothesis about monarch and viceroy butterflies by creating a digital simulation of the chemical reaction-diffusion process that creates the spatial patterns on wings. We want to see how easily one butterfly pattern can be switched to another very different-looking pattern by changing just one or two variables. In this manner, the prescient insight of Nabokov might be confirmed: a long gradual process of adaptive change may not be required for one type of butterfly to come to look like another.

“St. Petersburg has always been in the back of my mind”

As far as I know, it’s not your first time in St. Petersburg. When did you visit our city for the first time?

In 2002 I attended a conference at the Nabokov Museum. I had just published my first study of insect mimicry. I loved St. Petersburg, and I have wanted to come back ever since. That’s why it wasn’t hard to accept the offer to work at ITMO. The idea of returning had always been in the back of my mind.

After the coronavirus outbreak in Russia, you decided not to leave St. Petersburg. Why so?

I didn’t see any reason to leave. I feel my health is safe here. I have a nice home to shelter in place. When the Fulbright Program was suspended due to the pandemic, my position as a Public Scholar came to an end, and I was urged to return to the US. Fortunately, ITMO University allowed me to stay to complete my projects. I will stay until the end of May, as was planned initially.

When the emergency was declared, I had only just arrived in February. I am dedicated to my students. I didn’t want all the time and energy the students had already put into the class to be wasted – the initial stages are the hardest for any course. I wasn’t ready to quit. Of course, it would be better to have an opportunity to speak with my students in person. It's a pity that we can’t have that, but I hope the situation will improve and we’ll be able to meet again before the end of the term.

May I ask what you do in self-isolation?

I have several projects going on Nabokov’s legacy. I’m working on them with the former head of the Nabokov Museum, Tatiana Ponomareva. Shortly before the coronavirus outbreak, she had invited me to give a public presentation at the Herzen University. Now we’re trying to prepare an online substitute.

Other than that, I’m writing short stories. I may be better known for my work on science topics, but I think of myself as a novelist first. I’m working on a collection of stories that illustrate, in narrative form, biosemiotic theories of innovation and artistic creativity. That’s what I’m busy with in my free time. I also leave the house to take out the trash and get some groceries (laughs).

Did you have time to find any special locations in St. Petersburg? The ones that inspire you?

The Summer Palace of Peter the Great and the Summer Garden, which, I hope, will open on May 1st. When I was in Russia in 2002, I visited the summer Palace and Garden and I’ve thought about their beauty often in the past 18 years. I have been back to the gardens, which are still lovely even in winter.

Was there something that pleasantly surprised you during the trip? Or, on the opposite, puzzled you?

The biggest surprise was the good weather. That's the good news. The bad news: I brought mostly heavy winter clothes with me, as I thought it would be colder here than in New York. However, it’s actually warmer.

I was also amazed that anywhere I go there are people who speak English. However, it makes it harder to learn Russian. When I go to a store, I try to hide my accent, so that I can practice Russian, but everybody hears my accent and switches to English.

You’re planning to leave at the end of May. Wouldn’t you like to stay here, in St. Petersburg, for a longer time?

I own a farm in upstate New York, so I must get back to plant my vegetable garden by June. I am excited to try the Russia carrot and beet seeds I bought. But I’d like to come back to St. Petersburg to continue working on the projects I’ve started and won’t be able to finish because of the pandemic. I’d like to cooperate with the Vladimir Nabokov Society more, and I’m already planning to visit again in November.