You came to ITMO 25 years ago, when you were invited by Vladimir Parfenov as a lecturer to the then-Computer Technologies Department, which has since become legendary. Back then, ITMO didn’t have its programming champion status – what made you accept the invitation?

It wasn’t like I really had a choice. My teaching experience was only as a lecturer of professional development courses; I also wasn’t a renowned scientist, even though I had quite a few publications. So, suffice it to say, I wasn’t being offered any teaching positions.

I came to LITMO (the former name of ITMO University – Ed.) to teach part-time, alongside my job at the Avrora Scientific and Production Association (developer of ship control systems – Ed.). Among my students were very talented individuals, who went on to become PhDs and competitive programming stars. My task was to interest them in a subject they clearly didn’t need.

As I was starting at ITMO, Prof. Parfenov said to me: “You thought that life was passing you by, but it will only really begin once you join our department.” He happened to be right: the first 50 years of life had been good, but a new era began once I’d come to ITMO. It was one thing to work with adults in the industry and another – to teach supertalented kids who are one of a kind.

Our Rector, Vladimir Vasilyev, once told me that it wasn’t clear who got it better: me because I came to LITMO, or LITMO because it found me. I am certain that I am the luckiest – without LITMO, my life wouldn’t have been the same. When I defended my doctoral thesis, Dr. Vasilyev thanked me for choosing the university and becoming one more professor on staff.

I think this is your answer as to why I came to LITMO. Where else would I get such treatment? When you are welcomed with such warmth, you can’t help but respond with the same.

Vladimir Vasilyev, Vladimir Parfenov, and Anatoly Shalyto with the winners of ACM ICPC 2017. Credit: ITMO.NEWS

What strategy helped you build a strong IT school at ITMO in the 90s, as well as keep the best students and lecturers at the university?

I came to the strong foundation laid by professors Parfenov and Vasilyev in 1991. When I joined the Computer Technologies Department in 1998, the faculty didn’t conduct any research in its main field. To attract the most talented students, the department offered training in math, physics, programming, engineering, and advanced English.

My wish was to shift the department’s focus from physics and mathematics to computer technologies, so I started teaching automata-based programming, which gradually expanded into the validation of autonomous specifications and its connection to AI. I was hoping that sooner or later students would start suggesting projects within these or related topics.

The second challenge I needed to overcome was brain drain: our talented graduates were leaving for the industry. I came up with the following format: I started teaching third-year students, who I inspired to do research on automata-based programming. We would meet with groups of two students for several hours once every six weeks. At these meetings, we would talk about everything, from academic Russian to program documentation and science. I’d have no less than three meetings per semester with each group.

So, in total, each group would spend 12-15 hours working on a project with me – they would spend even more time preparing on their own. By the end of the semester, projects would typically not be complete, but I would still give students their final grade for the subject. Usually, they would still continue developing their projects with me. The catch being that I was the head of the State Examination Committee for Bachelor’s and Master’s theses…

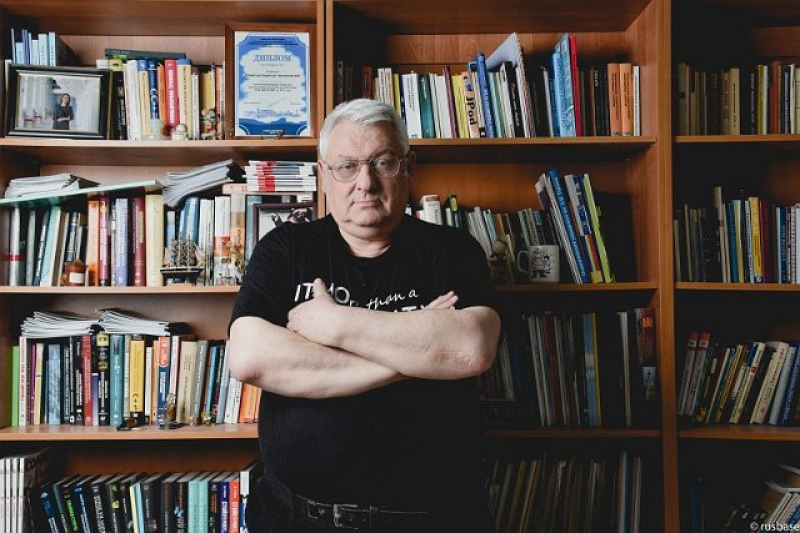

Anatoly Shalyto. Credit: ITMO.NEWS

In 2008, I negotiated agreements with a number of IT companies: they offered scholarships to talented students and graduates who would stay at ITMO to teach and do research. I persuaded the industry leaders by explaining that those who they fund will teach a next generation of top-notch programmers – who, in turn, would become these companies’ employees. JetBrains was one of the companies that joined the initiative: they ended up pledging 1% of their revenue for scholarships and 0.5% – for research funding. Revenue, mind you, not profit!

That’s how we ended up with highly sought-after professionals as lecturers at the department. Among them were Andrey Stankevich and Georgi Korneev, two-time winners of ICPC. Mr. Stankevich is very active at ITMO and elsewhere; he teaches summer and winter schools for competitive programmers – for 100-200 students each season.

Over the years, other programming champions have worked at the department, including Niyaz Nigmatullin and Gennady Korotkevich, two-time ICPC winners.

Vladimir Vasilyev, Vladimir Parfenov, Andrey Stankevich, and the winners of ACM ICPC 2013 Niyaz Nigmatullin, Gennady Korotkevich, and Mikhail Kever. Credit: ITMO University

All of these star programmers held classes and organized programming competitions for school and university students. We also did our best to discover and engage talents in research – later, they joined the International Laboratory “Computer Technologies,” organized as part of Project 5-100 (a nation-wide academic excellence initiative – Ed.) and headed by my former PhD student Vladimir Ulyantsev.

I am most proud of initiating research in bioinformatics and systems biology, despite the skepticism of my colleagues. Alexey Sergushichev, one of our graduates, now heads research in the field – he has publications in high-ranking journals, including Nature, Cell, and Immunity.

In her interview to ITMO.NEWS, my PhD student Arina Buzdalova said that my job is to create an atmosphere of success.

I hope that my story shows that ITMO turned into the alma mater of the world’s top programmers thanks to the efforts of not a select few, but many inspired students and professors.

The team of ITMO’s Computer Technologies Department in 2019. Credit: ITMO University

New times have brought new challenges, the major one being the need to train and thus solve the shortage of IT specialists that today’s market experiences. How can it be done quickly and efficiently?

If we don’t want to lose specialists, first and foremost, we need to make sure that our best minds stay and train others. How? We can do what I did at the beginning. We need to “save” each potential leaver so that there was at least one competent IT specialist left at each university. Companies should support young specialists. In addition to business support, there should be other kinds of financial aid for students, too, such as salaries and grants. At universities, they have to also involved in research and design projects.

Unfortunately, many people believe that the traditional education at universities fails to keep up with the market’s needs and trends and will shortly be replaced by online courses and self-education. What should universities do about this matter?

Absolutely nothing. I don’t think that taking a six-month program can be compared to studying for 6 years at ITMO. I know that today students don’t want to master difficult subjects, and virtually all employers and most heads of our educational programs support them in this regard. But the way I see it, students can’t even imagine what might come in handy in the future. They don’t understand that studying complex concepts boosts their brain power. For that reason, schools used to – and some still do – teach students Greek and Latin. It wasn’t because they wanted to produce future pharmacists, which is not an uncommon misconception. The great French mathematician Gaspard Monge once said that people tend to dislike the tension of the mind – yet added that only the charm that accompanies science can help overcome it. I stand and will continue to stand by this for as long as I can.

Nevertheless, online courses could be a big help for some. I know one woman in her 40s who had studied humanities. She even joined ITMO at some point, but it didn’t work out. She then signed up for a big data course, and I recently found out that she has since relocated to Finland for work. Certainly, courses can open up new opportunities, however, they won’t teach you to build next-gen computers or software products, like Kotlin, a programming language created by our alumni Andrey Breslav and Roman Elizarov, which was added as the preferred language for Android Studio by Google back in 2017.

The students and staff of ITMO’s Computer Technologies Department in 2016. From left to right: Artem Vasilyev, Niyaz Nigmatullin, Anatoly Shalyto, Maxim Buzdalov, Evgeny Kapun, Vladimir Parfenov, Gennady Korotkevich, Boris Minaev, Pavel Mavrin, and Andrey Stankevich. Credit: Valentin Blokh / sobaka.ru

You’re a veteran teacher, and, as shared by one of your graduates, you give your students a lot of freedom in the classroom. Why so and what is the main aspect of teaching for you?

I’m not a jazz expert, but I know that in jazz there's a principle that allows musicians to improvise within certain limits. If a student has proven themselves as a high achiever or driven researcher, I’m certain that they will do the right things even with all the freedom, whereas when given to the wrong person, it is doomed to go to waste. One of my former PhD students, currently the head of an IT company, keeps an eye on his workers when there isn't much to do and mercilessly dismisses all who waste this free time. Like me, he reckons that there is always work to be done and if you have extra downtime, you can work on a paper or study professional literature.

This is also about discipline. As some of the greats once put it, even if there's only one student in my class, I will deliver my lecture because that’s the way it is supposed to be and it’s important for that one student. At the same time, people who try to build a career with one hand and find money with the other rarely make it in the world. In my viewpoint, a person needs to excel first and money will come after. This is not the path for everyone but those who take the risk and win are tempered in this struggle – and that’s the type of people I like.

Not so long ago, you were awarded a badge of merit for mentorship along with three other people. What is the difference between a teacher and a mentor? And what makes a great mentor?

Some people envy me because I can get along with students, although I’m 55 years older than them. I think a mentor is someone who can speak the language of students and be accepted by them. They will talk to you and be honest, not thinking you are an old man who knows nothing about life. Though first-year students can beat me at programming, every day I do my best to show them that there’s something I’m better at and this might be of help to them.

What do you like the most in modern students?

I’m fascinated by their passion, professionalism, mind, and charisma. I have witnessed several generations of students: there was one type of people 20 years ago and they are a bit different now, but the best ones are always alike and great at something.

You’re turning 75 this year, and many students would envy your energy and enthusiasm. What’s your secret?

First of all, I have the best genetics. My parents lived to over 90 years each and stayed in good shape till their last day. It motivates me that my colleagues think of me highly – and not only here, at ITMO, but also at Avrora.

I always have something on my plate and this also keeps me going . I teach and write books (not only professional). Here are some of them: Заметки о мотивации (Notes on Motivation), Мои счастливые годы на кафедре “Компьютерные технологии” Университета ИТМО (My happy years at ITMO’s Computer Technologies Department), and Крохотки и не только… (Titbits and not only…). Also, my daughter Inna, an outstanding person who got to work at Yota and MTS, as well as headed St. Petersburg’s Committee for Tourism Development and even Roskino. Inna also has a daughter, my granddaughter, who I get to see several times a day thanks to modern technologies, which is always a pleasure for me. And, for sure, my natural charisma.