Bacterial infections remain a pressing health threat, linked to one in eight deaths worldwide, according to the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance. Their treatment usually involves antibiotics – medications that inhibit the function of or block the synthesis of harmful microorganisms to prevent their growth or reproduction. Antibiotics revolutionized medicine, successfully treating previously fatal diseases like pneumonia, tuberculosis, and syphilis. On the other side of the coin, they are prone to losing their effectiveness when used frequently. The reason is that bacteria start to evolve and mutate and thus become drug resistant. To extend the life of antibiotics, scientists seek to produce medications that target several bacterial proteins at once; thus, when one protein changes, the drug can link to another and continue to fight the disease.

New antibiotics require new chemical compounds. As a rule, researchers opt for high-throughput screening to check various molecules in databases for compliance with specific criteria: lack of toxicity, binding to target proteins, their synthesizability in laboratory conditions, etc. The process generally takes up to several weeks and is ill-suited for creating fundamentally new compounds. The solution could be machine learning, but it is far from flawless: most available algorithms can generate active molecules for only one protein, which is often not enough to create efficient, resistance-breaking medications.

ITMO researchers developed their own algorithm that searches for and creates new compounds targeted at two bacterial proteins. With its help, the chemists managed to produce 56 new compounds based on benzimidazole – a class of compounds that exhibit a high level of antibacterial activity and, as the scientists note, are rarely used in medications. In the long run, the developed molecules may serve as a basis for antibiotics against resistant strains of Escherichia coli (E. coli) – a highly common pathogen that rapidly mutates and becomes resistant to antibiotics. In humans, it causes severe gastrointestinal conditions, including abdominal cramps, vomiting and diarrhea, urinary tract and gallbladder infections, wound infections, pneumonia, and meningitis.

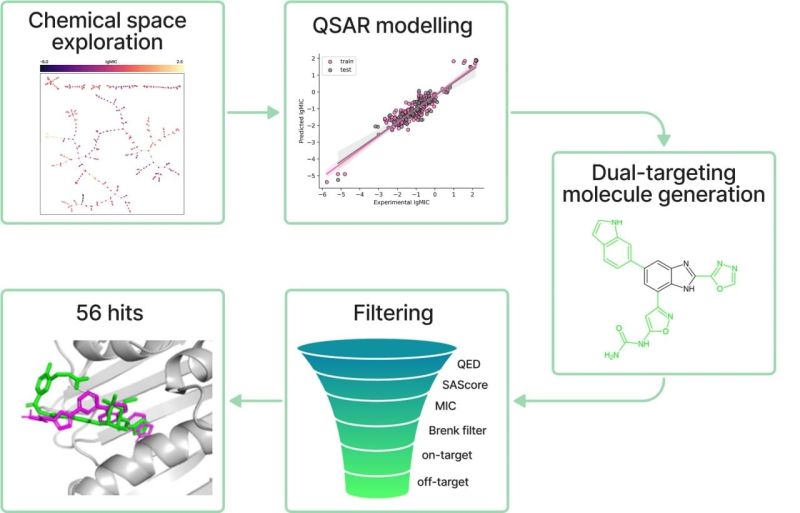

The research stages include: studying the chemical space of benzimidazole, building a predictive model, generating molecules, evaluating the properties of generated molecules, and molecular modeling. Illustration courtesy of Anastasia Orlova

Taking a drug compound-generating algorithm developed by the AIRI Institute, the scientists adapted it to work with antibiotics and trained it to produce molecules for two target proteins – GyrA and GyrB. These proteins are essential to the survival and reproduction of resistant gram-negative bacteria. These bacteria are less treatable by antibiotics and can cause severe diseases in humans. Unlike its counterparts, the algorithm makes it possible to generate molecules with a vast number of properties and ensure their synthesizability.

The algorithm sorts molecules based on their properties; these are synthesizability, lack of toxicity and side effects, binding to target proteins, similarities to other medications, and biological activity. A built-in software model forecasts the molecules' activity levels – in sample tests of common chemical compounds, it has demonstrated 81% accuracy.

The team examined the generated compounds using computational methods. Together with their colleagues from the AIRI Institute, they checked the molecules via the free energy perturbation (FEP) method, which uses computer modeling to turn one molecule into another and accurately calculate the energy difference between the two. As a result, the researchers found two compounds with greater activity than that of novobiocin.

The next step for the researchers is laboratory testing.

“By doing lab tests, we can see how active the compounds we obtained really are. Out of all selected candidates, we usually have two or three options. If our compounds prove efficient, we may start thinking about a patent; we're already looking for a laboratory,” says Anastasia Orlova, an author of the paper, a PhD student, and an engineer at ITMO’s Advanced Engineering School.

Anastasia Orlova. Photo by ITMO’s Advanced Engineering School

In the future, the algorithm can be tailored to search for medications against other bacteria, as well as antifungal and antiviral therapy. For that, the team will need to collect a database of existing molecules, develop a model for predicting molecular activity, incorporate it into the algorithm, and then train it, taking into account the newly-installed model and proteins at target. As of now, the model is in the public domain, so chemists can freely use it to predict the activity of benzimidazole-based antibiotics.