Chemistry and ownership in one study

Some of the common methods to identify a painting’s authenticity are ultraviolet luminescence, X-ray diffraction, infrared reflectography, and X-ray fluorescence. However, all of them allow specialists to analyze only a painting’s exterior, without looking into the molecular compounds of the paint used to create it.

Researchers from ITMO’s Heritage Science Lab have developed a semiquantative method based on infrared spectroscopy that can solve several tasks in just 30 seconds. Not only does the suggested method identify a painting’s chemical composition, evaluating the concentration and weight content of a specific substance, but it also makes it possible to determine the century when specific layers of paint have been applied. Using this method, researchers and art historians will be able to tell if they are working with an original painting and whether it was ever subject to restoration, as well as discover the pigments and binding materials in oil paint that were characteristic of a certain artist.

“One sure way to analyze a painting is to look at the pigments used to create it, which is not a simple task, seeing as there are over 15 different blue pigments alone. For instance, Prussian blue was created in the early 18th century and cobalt blue appeared only later. Knowing this, we can tell with certainty that if there is cobalt blue used in an Aivazovsky painting, then the artist must’ve created this piece after a specific date. And the process goes the same for every shade. In this study, we look at the binder of the paint, which allows us to not only identify the material used (be it oil or acrylic), but also the century when it was applied,” says Ivan Andreev, one of the article’s authors, a PhD student at ITMO’s Faculty of Photonics, and a specialist at the Technological Research Department of the State Russian Museum.

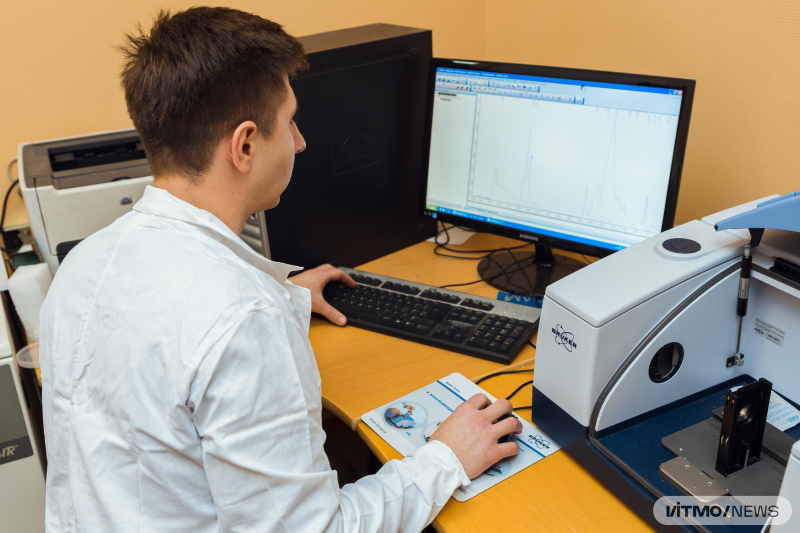

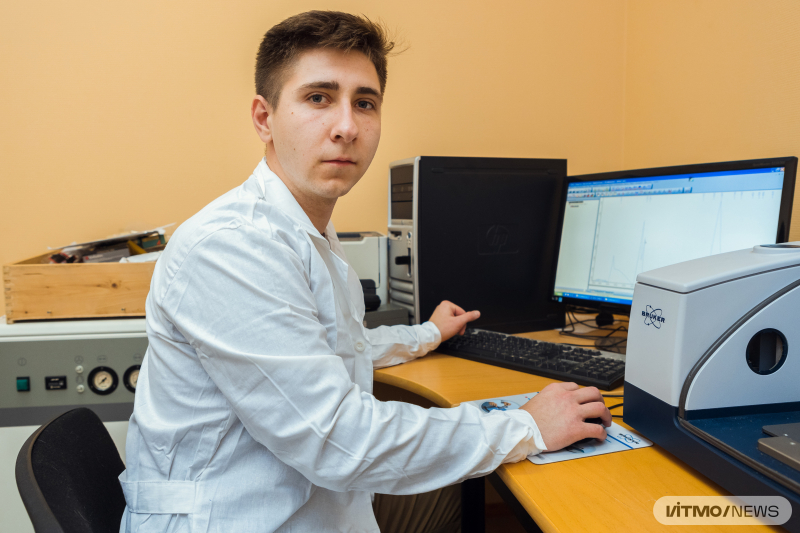

Ivan Andreev. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

Analyzing a copy of an Aivazovsky piece

As a test object for the new method, the researchers chose a copy of Ivan Aivazovsky’s painting A Bird’s-Eye View of the Prince Islands near Constantinople on the Marmara Sea, created by one of his contemporaries, who remained anonymous. The choice of Aivazovsky specifically wasn’t random: being a very prominent and prolific artist of the 19th century, he has left quite an extensive heritage – and his work has often fallen victim to forgery in the past.

“Ivan Aivazovsky is a very popular artist, who gained fame while he was still alive – which is one of the reasons for the many forgeries of his work. That’s why it is so important to not only present his creations to the public, but do so after an aesthetic and historical evaluation, a scientific and technological study that will allow us to talk about the context of his art. Through technological analysis, we can learn about the artist’s style, technique, and preferred materials, which allows us to tell a copy from the original and determine the significance of a piece. At the same time, a deeper analysis of a copy will help us identify the most characteristic traits of a specific historical period,” shares Aleksandra Smolyanskaya, an art historian, a PR specialist at the State Russian Museum, and a researcher at ITMO’s Faculty of Photonics.

Aleksandra Smolyanskaya in front of Ivan Aivazovsky's Wave. Photo by Ivan Andreev

In the study, the researchers cut out a piece of the copy and asked restorers from the State Russian Museum to put a signature on it in oil paint, which they then covered with more paint in a different color. On the other side of the piece, the specialists sketched a human head on a brown background. After that, samples were taken from both sides of the pieces, then inserted into a diamond crystal and subjected to infrared radiation. In this process, a part of the waves were absorbed by the binder, while a part of them went through. After this experiment, the researchers compared the absorption spectra of binders and pigments from the copy with each other and with samples from the databases of the museum and ITMO’s Heritage Science Lab.

Read also:

Heritage Science at ITMO: Collaboration With Russian Museum and French Colleagues

How Russian and French Researchers are Helping to Restore Classic Art

Nanolasers, MRI, and Cultural Heritage: ITMO University Wins Three Megagrants

As a result, they discovered that the degree of polymerization in oil paint is different in layers from different periods. In other words, after application, the paint hardens, but it can still engage in chemical reactions with the pigments it is made from. In turn, the changes in the chemical composition of the pigments that happened at different times are seen differently in the infrared spectrum. Thanks to this discovery, the researchers can now say precisely in which century a certain layer of paint was applied and thus identify a painting’s authenticity.

In the future, specialists from the State Russian Museum are planning to use the new method in their expert analysis to confirm a piece’s originality and also adapt it to work with paintings from other periods, such as the Russian avant-garde of the 1910s, which is also characterized by an abundance of forged and copied pieces.

This research was supported by a grant from Order No. 220 of the Government of the Russian Federation dated April 9, 2010.

Reference: Ivan Andreev, Sergey Sirro, Anastasiya Lykina, Aleksandra Smolyanskaya, Alexander Minin, Olga Kravtsenyuk, Michel Menu and Olga Smolyanskaya. Necessity and Use of a Multilayer Test Object Based on an Anonymous 19th Century Copy of a Painting by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817–1900). Heritage 2022, 5(4), 2022.