The Great Patriotic War (the 1941-1945 period of WWII that involved the USSR – Ed.) began on June 22, 1941; by September, the Nazis had encircled Leningrad. The first evacuations, however, began before then: 135 pupils and staff of Kindergarten No. 49 were first taken to the Borovichsky District (Leningrad Oblast) but, when the Nazi forces advanced deeper into the country, had to return home and face the harsh winter, famine, and bombardment. Many lost their parents in the early years of the war. Therefore, Kindergarten No. 49 became an orphanage (Orphanage No. 51) and accepted children from other kindergartens.

The next attempt was to transport the orphanage to Krasnodar Krai. In April 1942, 108 children were evacuated across Ladoga Lake in trucks up to their sides in water and strafed by German fighter planes. Two children were wounded and left at an evacuation hospital, while the rest of the group headed by train towards the village of Timashevka. For 22 days, the teachers did their best to help, getting hot water, checking for lice, and taking the children on walks when possible. However, some diseases – like scurvy and scabies – could only be treated when the group reached their destination, where they could rest and bathe after their long journey.

It seemed they were finally safe. But in June 1942, Nazi troops broke past the Soviet defenses and proceeded into the Caucasus and Kuban. The group had to get moving again; they caught the last train on August 7 and headed first to Novorossiysk and then through Sukhumi, Tbilisi, and Yerevan to Sanahin. This was where the war ended for the children. Locals gave them food and even shelter while the local orphanage was under renovation.

The history of Orphanage No. 51 is known thanks to the institution’s head, Khana Gershenok, who kept her school notebooks, staff notes and documents, and diary. Based on these sources, the staff of the State Memorial Museum of Leningrad Defense and Siege organized a temporary exhibition under the title of Route to Sanahin. The Story of One Orphanage, which recounts the struggles of the children during those terrible times.

To preserve a memory of the exhibition, the museum administration decided to create a digital memorial – a fully accurate 3D model of the entire display. To do that, they invited the staff of ITMO University; this is far from the first collaboration between the two organizations.

The virtual exhibition. Images courtesy of the project team

According to Nikita Prigodich, an associate professor at ITMO’s Faculty of Technological Management and Innovations, digital copies of objects of cultural and historical heritage have been around for a while; the field is quite well-developed both in methodology and in theory. At ITMO, research on the subject is carried out by students of the Master’s program Multimedia Technologies, Design, and Usability. Still, the conversion of exhibition spaces into digital form is a noticeably rarer occurrence.

“There are some successful examples of several major museums around the world that have converted their permanent exhibitions into virtual spaces. This allows people to visit those museums from anywhere in the world. Digitizing temporary exhibitions, on the other hand, allows us to preserve them in permanent form. This is what our students’ work has showcased. The exhibition Route to Sanahin may no longer exist, but everyone can still explore it in digital form,” explains Nikita Prigodich.

The 3D model was created by two first-year ITMO students, Elena Starostina from the Faculty of Software Engineering and Computer Systems and Ilya Morgaev from the Faculty of Technological Management and Innovations. The project curator was Galina Zhirkova, the director of the university’s Center of Social Sciences and Humanities.

“The stories of the children of besieged Leningrad are a very important and personal subject to me. I know people who’ve spent their childhood there during that time. But, for obvious reasons, the survivors don’t like to share details; these are very difficult memories for them. So, I’ve decided to study the history of the evacuation myself using historical sources,” explains Ilya Morgaev.

Work on the project continued for several weeks. First, the museum staff organized a tour of the exhibition for the students, presented them with all the necessary historical documents, and consulted them on their questions. Then, the project team began to digitize the exhibition.

“It was important to us to preserve and maintain the visual atmosphere and the spatial solutions of the exhibition’s design; thus, we settled on 3D modeling. In order to clearly record the objects, we scanned them with a lidar and made a lot of photos, which we then processed with neural networks. But the visualization had some serious issues, so we made the models ourselves in Blender,” says Ilya Morgaev.

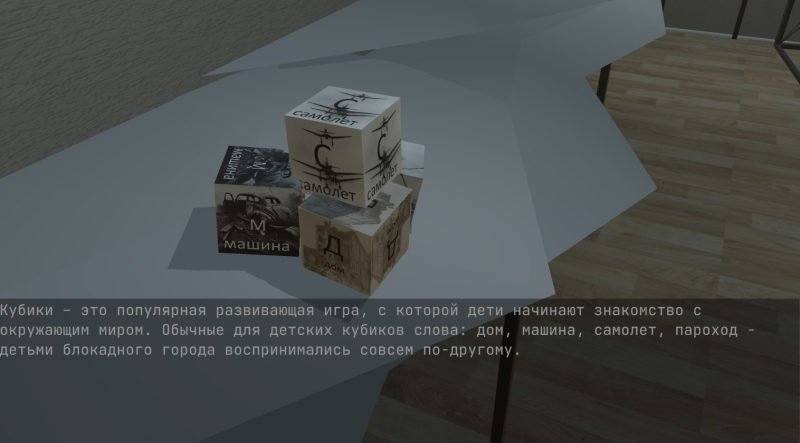

Just like the original exhibition, the digital copy covers all the stages of the orphanage’s evacuation, with detailed descriptions presented on plaques. Dioramas of gray Leningrad houses, with some lights still burning in the windows, ice floes reminiscent of the trek across Lake Ladoga, a train car on its way to Novorossiysk, and the exhaust funnel of a steamboat heading to Tbilisi from Sukhumi. The exhibition concludes with a mockup room divider, behind which the visitors can glimpse the sunny Sanahin – the symbol of a successful escape and a brighter future.

In the future, the 3D model of the exhibition will be published on the website of the State Memorial Museum of Leningrad Defense and Siege. Then, anyone with interest in the subject will be able to explore the history of the evacuation to Sanahin.