It is for the third time that the Forum of Science Communicators has been held in Russia. The event was organized by the Association for Communication in Education and Science (AKSON), an association of specialists in the field of science journalism and PR at the country’s scientific and educational organizations, and ITMO University, the Grand Prix winner of the 2018 Communication Laboratory award.

“Our community grows and develops, which for me as the president of the Association means that what we are doing is seen as helpful by our colleagues, and we always have and will set store by feedback. With the forum being organized for the third year in a row, it is gratifying to observe that it has become a tradition rather than staying a one-time event. We are growing with each year that passes; the event continues to expand in scope. For instance, this year’s forum included a new feature in the form of a further training program; we have also launched an open call for applications for section reports by participants, which were selected by a special program committee. We have held several partner sessions initiated by the organization in question. Thus, we have managed to broaden the range of topics discussed and achieve a better understanding of what the community needs, which is the main priority for the Association,” commented Alexandra Borisova, president of the Association for Communication in Education and Science.

One of AKSON’s main goals is the integration of the Russian science communication community into international organizations for science communicators and journalists. This year, alongside other associations from the UK, Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Switzerland, AKSON was named as one of the founders of the European Federation for Science Journalism (EFSJ), and also joined the World Federation of Science Journalists (WFSJ).

“I remember how the community started out in the 2010s. Back then, it was still quite a niche community, but it has since evolved into something really valuable. Before the forum, we had organized a two-day further training school together with the National Training Foundation (NTF), which welcomed science communication enthusiasts from all over the country. I think that this is a right move because we have to be vocal about the achievements of Russian science, but it is important to not only do so inside of the country, but also try to import the information to the international level. In this, we are lucky that this year’s forum was attended by prominent international experts. Many in the field of science communication and journalism has been done abroad, and we believe that these practices need to be adapted to Russian realities,” said Dmitry Malkov, head of ITMO University’s Science Communication Center.

Held at ITMO University, the Third Forum of Science Communicators has become the most large-scale one to date. The program included a wide and diverse range of discussions on different aspects of work of science communicators and journalists, large presence of international expertise and an expansive exhibition space. The pre-conference agenda included both educational and cultural components: the participants of the forum could boost their skills at the School of Science Communication for Universities and attend tours of Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant, St. Petersburg Atomic Energy Information Center, and Research and Development Center for Thin-Film Technologies in Energetics. The forum itself concluded with the awards ceremony for the 2019 Communication Laboratory prize.

Among the key topics of the 2019 forum were professional and ethical standards in science journalism, research on social attitudes to science and technologies, journalism and communication in medicine, science museums and festivals, communication in knowledge-intensive business and technologies transfer, education in science communication and journalism, promotion of Russian scientific news in international media and the state strategy in the field of science communication.

Serving as partners of the 2019 Forum of Science Communicators were the Rusnano Fund for Infrastructure and Educational Programs, Russian Science Foundation, the company MEL Science, the publishing house Alpina Non-Fiction, the news portals Laba.Media, Indicator, and XX2 Century, the magazine Science and Life, St. Petersburg Atomic Energy Information Center, and National Training Foundation.

Contributing with a plenary presentation was Michele Catanzaro, physicist, science journalist, and laureate of the King of Spain International Journalism Prize (2014), European Science Writer of the Year (2016) and author at Nature, The Guardian, Der Spiegel and a number of other publications. The expert shared his views on the future of science journalism and weighed in on the risks and challenges in the field.

On the impact of journalism on science and of science on journalism

In 2011 and 2016, there were cases of murdered scientists who did research in the field of nano- and biotechnologies being found on the campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The responsibility for the murders was claimed by a group of people that advocate against the alienation of humans from nature (Individuals Tending Toward the Wild, ITS). At the same time, a number of publications appeared on nano and biotechnologies in science journalism media, one of the most impactful being one by a famous futurist Eric Drexler, who posited that nanotechnologies will cause a radical transformation of the world. All literature appearing at that moment bore references to Ted Kaczynski, an American mathematician who cut himself off of the civilization and began sending homemade bombs to people who, in his opinion, were responsible for the advancement of technological progress.

“Many researchers believe that we will free ourselves from our physical shells, from nature, and will be able to upload all our memories onto a memory card and stop existing in the material world altogether. But we haven’t reached this stage yet. Oftentimes the ideas related to nano- and biotechnologies are promoted by scientists and scientific organizations using hype narratives, which explains why the topic is often surrounded by exaggerations. I’m not saying that this hype was the reason that the scientists were killed, but rather using this chilling example to demonstrate that happenings in the field of science can sometimes lead to the loss of human lives. This is an example of a negative impact of communication on science and people’s lives,” explained Michele Catanzaro.

But there are many examples of journalism impacting science in a more positive way. At the beginning of the 2000s, doctor Andrew Wakefield published a research paper claiming a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and the development of autism in children, which led to a decrease in the use of vaccine in the UK. But an independent investigation by reporter Brian Deer exposed Wakefield for being a fraud, demonstrating how the latter cherry-picked the data that supported his claim and identifying that Wakefield had been involved with pharmaceutical companies, leading to undisclosed financial conflicts of interest on his part. The medical journal The Lancet, which initially published the article, revoked it after the results of Deer’s investigation were made public.

On propaganda

Communication between science and journalism often seems comprehensible and objective, leaving all personal views behind, but it’s important to understand that these can and do influence the process as propaganda. In 1998, a research paper was published that set forth that from all the articles published in the world’s seven largest papers and connected with publications in the world’s four largest scientific journals (Nature, Science, Lancet and BMJ), 84% were based on press releases, while only 16% of materials contained information independently gathered by the journalist authors.

“Institutional communication has to be effective and strive to achieve the goal of forming a unified agenda, but problems do arise: another research analyzing 127 press releases found that only 23% of them actually disclosed their limitations brought about the financial connection that the finding in question had with the industry. Failing to disclose the industry’s ulterior interests can lead to serious consequences. At the same time, propaganda is very often used to increase the visibility of scientists and researchers in a specific institution,” shared the expert.

Why researchers and science journalists sometimes communicate information that is not objective

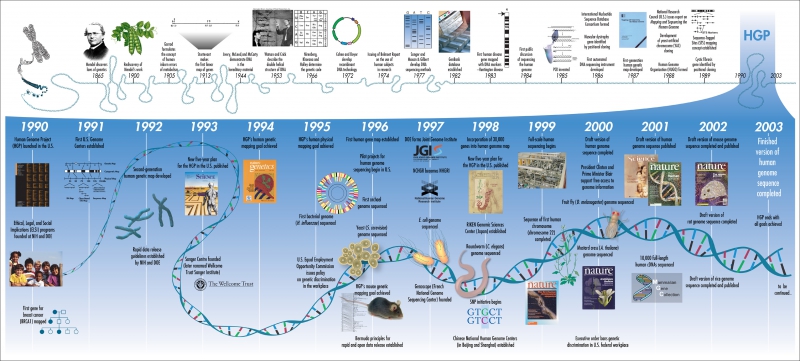

When The Human Genome Project was launched, experts often made statements that today would sound shocking. For instance, the then-editor of the journal Nature could be heard saying that introducing changes to the genome can lead to humans growing new limbs. Ten years after, a Nature op-ed suggested that genome-related medicine was still in its infancy and the world became a little too obsessed with the human genome. Why did such a statement occur?

One of the reasons was the price of the project. Because a lot of money had been invested in the project, scientists and science communicators tended to inflate its value. There was a less obvious reason, too: the human genome narrative was often mentioned in relation to heredity. For example, there were statements which claimed that a person’s appearance and intellectual capacities were dictated by heredity, while at the same time playing down the importance of other crucial aspects such as the environment, education, and the quality of healthcare. The post-Reagan era had a strong bias towards nature, cultivating the ideas on the dominant role of heredity rather than acquisition of traits.

Why journalists fall for propaganda

Today, the whole field of journalism is gripped by a crisis. In Europe and the US, journalism has seen major cuts brought about by the financial crisis, as a result of which the number of journalists has fallen and the number of journalistic tasks has risen. In this situation, to receive a press release with all the information at the ready seems like the saving grace: all you had to do was to edit it a little and publish it. But there are other crises: we still don’t know how to properly work with the internet, how to monetize it. New York Times and Washington Post found their ways of doing it, but it’s not a given that other mass media can follow their example.

Another reason why journalists buy into propaganda stems from professional crisis. In the West, mass media are being bought out by major corporations who then manage it like they would a shoes factory: democratic principles don’t even come close.

But there are crises inherent to science journalism itself. Historically, science journalism has always had the tendency of lacking in critical thinking. William Laurence, the first journalist to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize, covered the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Japan for New York Times, at the same time getting money from the US Department of Defense. This is an example of ambiguities in science journalism.

Approaches in science journalism

Investigative journalism

In 2016, Michele Catanzaro was awarded the title of European Science Writer of the Year for his investigation that allowed to free from prison a person that was falsely proclaimed guilty based on phonetic voice analysis.

“A car washer was charged with drug trafficking because experts found that his voice resembled the recording of the suspect’s voice. For a Spanish-speaking person, it was evident that the dialect of Spanish spoken by the suspect was widespread in Latin America, but the one who was charged spoke Spanish as current in Spain. Seven reports were published that refuted the findings of the first evaluation. The investigation was conducted by four journalists coming from different countries. We established that there were at least 30 similar cases where law enforcement agencies’ incorrect actions resulted in faulty charges. Phonetic voice analysis is a method that has been in use since the 1970s; though still popular, it is largely outdated. We discovered that only a few experts today use modern methods of voice analysis. It is the data we published that helped free an innocent person from prison. It wasn’t published in a scientific journal, but science still played a central role in this story. Our main message is, we have to do more to approach science from the journalistic point of view, and journalism from the scientific one,” shared the journalist.

Collaborative and data journalism

A large number of scientists left Spain in 2009 in connection with the financial crisis, but the government proliferated the view that the losses were being repleted by the number of researchers that were arriving in the country. This statement wasn’t supported by any data. Together with his colleagues, Michele Catanzaro sent out surveys to the scientists who had left and received 400 answers explaining that the former couldn’t return because of the crisis only. Drawing from the survey results, the researchers were able to create a common collaborative story on mass migration of scientists. Michele Catanzaro and his colleagues also created a website which had all the data on the research conducted, including information on the emigrated scientists and the topics they worked on. All this led to the discovery that there were a lot more scientists leaving that coming into the country.

Narrative journalism, sensoric journalism and gamification

Sometimes it is appropriate for a journalist to focus not on scientists per se but on their personal stories as people with emotions and their own perception of what is happening.

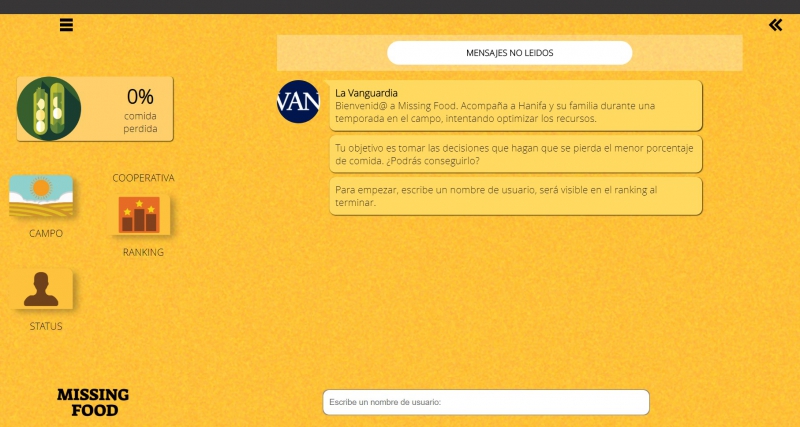

Sensoric journalism is the most innovative approach that involves using data collected from sensors for creating and narrating stories.

Another approach, gamification, implies that a journalist tells a story through interactive games. In 2017, a popular Spanish publication La Vanguardia launched the game Missing Food as part of their coverage of the disappearance of food in Africa (around 30% of food delivered to Africa as part of humanitarian aid goes missing, exacerbating the hunger in the region). Readers can not only read the story but, within the framework of the game, meet and interact with an African family as they make the important decision of where to store seeds and what to buy, make their own decision and see the consequences to which it leads: the loss of food, money or health.