Why did you choose ITMO?

I decided to come here based on a recommendation from one of my professors in France. Before that, I’d actually applied to a program in Germany, but eventually it was canceled, so I didn’t get the grant. It was then that my professor helped me find another option at a department that he collaborated with, which happened to be ITMO’s Faculty of Physics. He told me that ITMO’s researchers produce high-quality research, so I decided to apply. Another reason for this choice was that I had been interested in metamaterials for a while and wanted to learn more about this topic.

Where did you get your Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees?

I did a double degree in chemical engineering and materials science. I started out as a chemical engineer at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (Barcelona, Spain) and then in my third year I learned about a program that allowed students to get a double degree at the European School of Materials Engineering (EEIGM) in Nancy, France. So I applied and got in.

In France, I studied materials science. During that time I also went on an exchange semester to the National University of Science and Technology (MISIS) in Moscow to study condensed matter physics. After that, I went back to France, where I worked at the Jean Lamour Institute doing research on plasmonic structures.

Then, I abandoned optics for a while and got more into condensed matter as I went to CERN in Switzerland, where I was part of an international team dedicated to investigating materials for the superconducting cables of the future circular collider, the potential substitute of the LHC (Large Hadron Collider). Eventually, I decided I wanted to get back into optics and that is why I came to ITMO.

Globe of Science and Innovation, CERN. Credit: depositphotos.com

Why did you decide to travel for your career?

I felt like I hadn’t found myself scientifically yet. During the course of my studies I learned about many interesting topics, but never had the chance to delve deeply into any of them. Unfortunately, the value of fundamental research in Spain is largely underestimated, and so the opportunities to pursue a PhD in something that you are really passionate about are scarce, or nonexistent. Going abroad significantly enriched my scientific experience, helped me figure out what really motivated me, and gave me the chance to build my career on it.

Why did you decide to do research in the field of optics?

Electromagnetism was something like a hobby for me when I studied engineering in Spain: over summer holidays, I used to bury my nose in textbooks and solve problems. Coincidentally, one of my professors in France worked in plasmonics and I was lucky enough to be offered a research internship, where I got to learn more about this topic.

Another coincidence was that it turned out that my project in Moscow was connected to toroidal moments, a hot topic in modern nanophotonics. With this experience and the background I already had on fundamental electromagnetism, I grew fascinated with light-matter interactions and nanoscale optics.

Were you nervous about moving here?

I’d already been to Russia, so I knew more or less what to expect. Of course, I hadn’t been to St. Petersburg, so I had no way of knowing if it was going to be different from Moscow.

My main fear was about being so very far away from my country. And I was also apprehensive of the cold – I am from a hot part of Spain and I really miss the sun here. But I was really motivated by my scientific interests, so I never really had serious concerns.

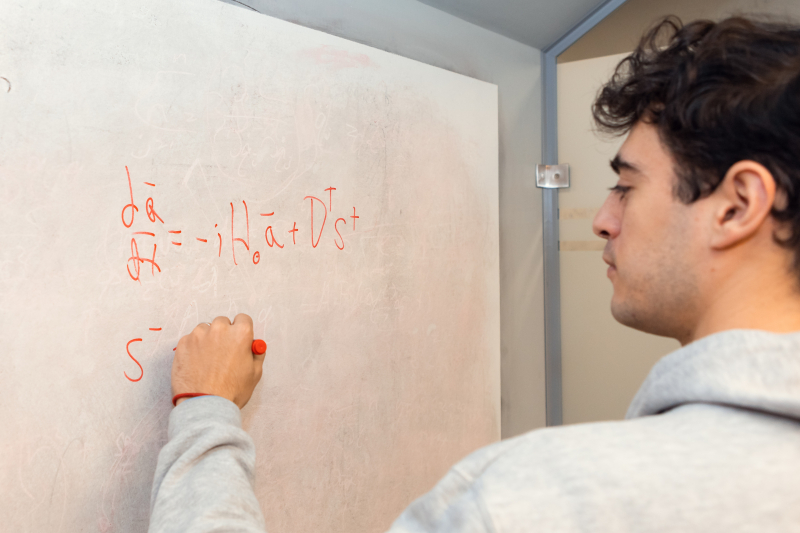

Adria Canos Valero. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

Did you face any difficulties as an international student?

I am not sure if this is common for students of other levels, but I felt a little left out, which I find normal given the fact that I am in a culture different from my own and I speak a different language. Despite the university’s best efforts to integrate everyone into an English-speaking environment, I don’t think it’s fully accomplishable. On the other hand, I find it would’ve been better if international students had more opportunities to learn Russian, because language is the main path to immersing oneself into a country’s culture. So that’s why communication was my main problem – I faced a general feeling of isolation for several years, but now I’ve overcome it.

Moreover, Russia has helped me grow both scientifically and personally. I recently married my Russian girlfriend. During most of my time here, her support has been key for my adaptation. On top of that, I've also grasped enough Russian to feel comfortable visiting a doctor or shopping.

However, everyday experience is not enough; even at university there are many administrative tasks that you can solve only if you are fluent in Russian or rely on someone else to do it for you. Often, you feel responsible for taking up that person’s time.

In that sense, I think the university cares too much about its international students. In my opinion, it could be done differently. They shouldn’t handle our tasks for us but instead teach us how we can handle them ourselves.

What advantages does ITMO have compared to other universities you studied at?

Here, you get the freedom to develop your own projects and ideas as long as they are within the scope of your topic. Even Bachelor’s students, with a bit of effort and motivation, can publish an article in an international journal. This is quite encouraged and recognized.

At ITMO you also have enough time to do your research as a PhD student, because you have to dedicate very little time to courses and administrative tasks. The system is built in a way that allows you to fully focus on research.

Adria Canos Valero. Photo by Dmitry Grigoryev, ITMO.NEWS

Are you planning to stay in Russia after you get your PhD?

Probably not. I do feel more comfortable here now, and I’ve managed to build a life for myself. I am very happy, I have my own family, I am relatively successful at work, and I more or less know the language – at least I know enough to handle everyday tasks.

However, it’s still not my culture and I really miss the sun – I even have to take supplements to compensate for it. The problem is also that the salaries here are not competitive internationally. It’s okay if you stay in Russia, but in other countries the salary is higher and you can afford to travel more and have a higher quality of life. It’s important for me and my wife to have enough resources.

Moreover, I find that the food is generally of a lower quality here – and you have to pay significantly more to find something of a higher quality. In Spain and most other southern european countries, however, this is not a problem. So, I am not saying that I will go back to Spain, but I will definitely look for other options besides Russia.