The idea behind the workshop came from Anton Schegolev, a first-year student of ITMO’s Master’s program in Art & Science. He is a sound artist who has taken part in such media art festivals as Cyberfest, Ars Electronica, Presence, and the Access Modes exhibition (you can learn more about him in our overview of this year’s Art & Science students).

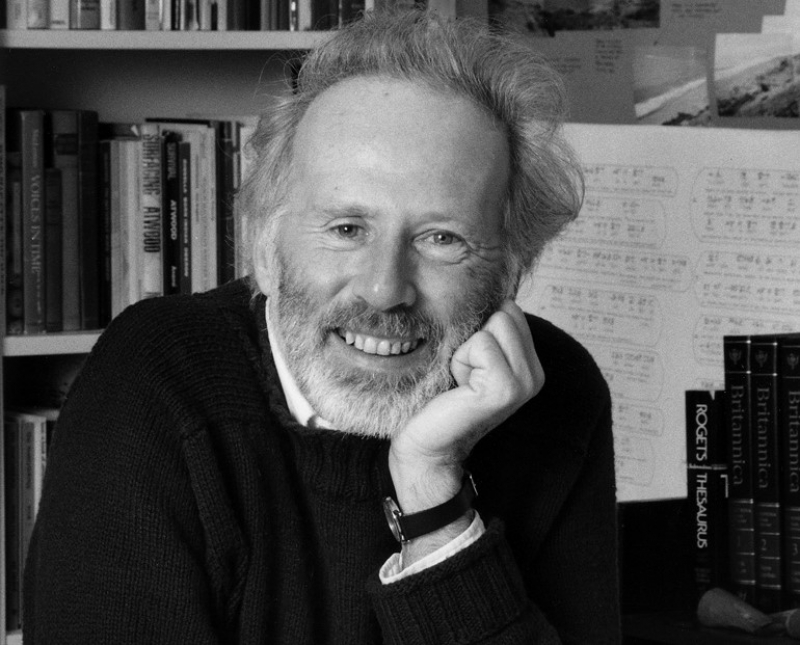

A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-making written by Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer served as a theoretical basis for the workshop.

According to Schafer, any space has its own unique set of sounds and noises that all significantly influence a person’s psychological and emotional state – most often, however, this influence remains unnoticed.

This combination of sound and noises he called a soundscape, a term that can be applied to cities, countries, or natural sites, as well as to smaller spaces like apartments, stores, bars, or coffee shops.

Acoustic ecology

Schafer studied the way soundscapes are affected by industrial and man-made factors. It was he who coined the terms acoustic ecology and noise pollution to evaluate the destructive effects caused by these factors.

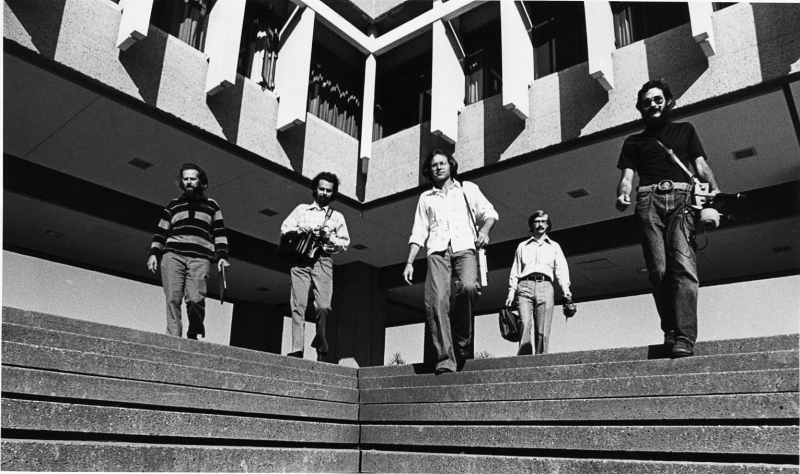

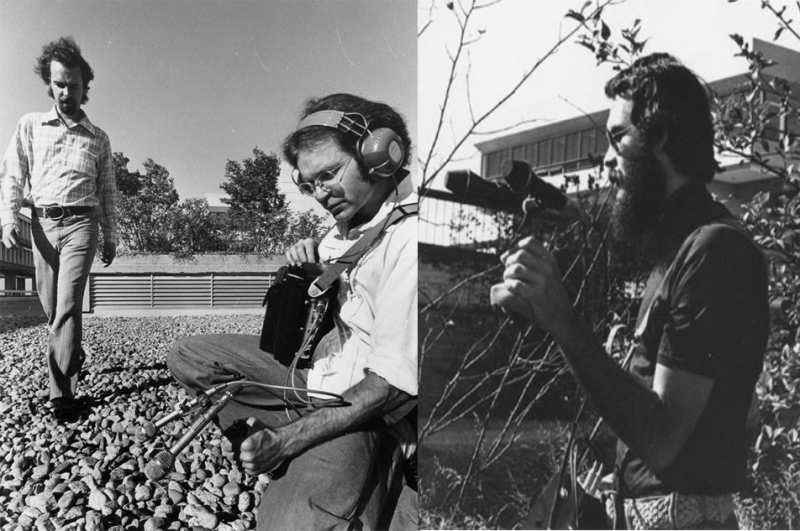

Over many years, he noted the way global warming and urbanization affect natural soundscapes. In the 1970s, he founded the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University, Canada. As part of the project a library of over 300 cassettes and several albums were collected, for instance, The Vancouver Soundscape and Five Village Soundscapes with sounders recorded in the villages of Germany, Sweden, Italy, France, and Scotland (you can find them in the archive at the Simon Fraser University website).

Much later, in 2009, Schafer’s research was recreated by scientists from Tampere University of Applied Sciences, Finland, who published the work Acoustic Environment in Change.

The main problem of any city space, according to Schafer and his followers, is noise pollution. Due to the large amounts of loud and monotonous noises, we experience psychoacoustic masking – it leads to soundscapes becoming extremely bleak and uncomfortable and makes separating single elements practically impossible. As we got used to this permanent noise around us, we stopped paying attention to the sounds surrounding us and the way they affect our mood and well-being.

Going back to active listening

Schafer’s A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Sound-making was originally meant for composers and sound artists but it can actually benefit anyone wishing to enrich their daily experience and become more involved and conscious.

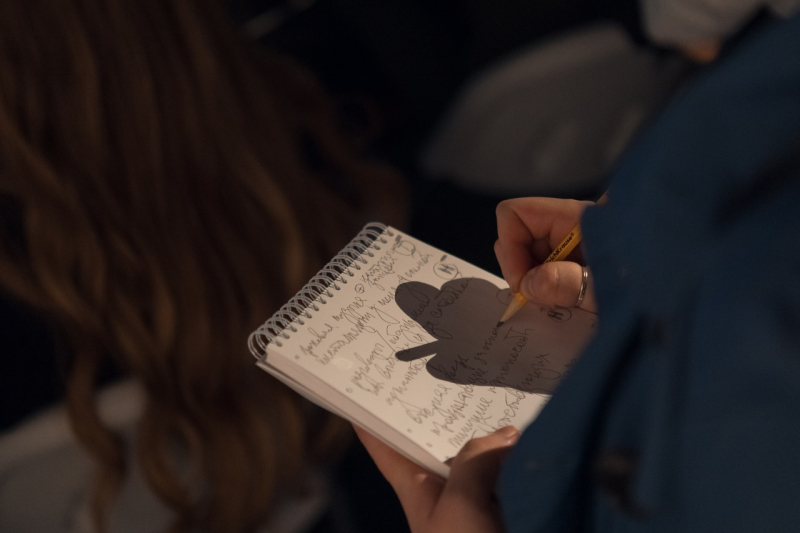

Each and every exercise is meant to move your focus to acoustic perception and active listening. For example, Schafer suggests keeping a diary to jot down the first sounds you hear when you wake up and the last sounds you hear before falling asleep, the loudest sound of the day, and the most surprising one.

You can also start collecting sounds by paying attention to the noises people make while walking or analysing the sound contents of your apartment.

Otherwise, you can simply go outside and listen to everything that happens around you – it turns out, the world is filled with incredible sounds that are constantly changing depending on the hour or the season (for instance, you’ll notice that summer sounds are more hollow, while winter ones are muffled).

You can note every sound and categorize it based on its source (industrial, man-made, natural), volume, distance, and (un)pleasantness. Finally, you can describe each of them: thin or thick, calming or aggressive, annoying or barely noticeable.

Marking sounds and your reactions to them is almost a meditation that broadens your perception and leads to extraordinary discoveries. For instance, you might learn that you like your favorite coffee shop because it is located in a quiet place and is full of textiles and carpets that absorb sounds. While you can’t work productively at home because of your loud fridge or the nearby construction site.

You might also discover the link between your visual and auditory perception: for example, if you want to separate one particular instrument at a concert, you can simply focus your eyes on it. You can also “hear” a picture or video that has no sound – we have a whole library of them in our head anyway.

In one of his exercises, Schafer suggests imagining a spade entering soil, snow, or sand – every one of us will instantaneously “hear” the accompanying sound in their head.

Soundscapes as seen in urban studies

The World Soundscape Project founded by Schafer continues to act as a global community of acoustic ecology enthusiasts. On July 18 every year they host International Listening Day. Many of Schafer’s followers now have their own YouTube channels with sound tours or give TEDx talks.

Acoustic ecologists proved how important it is to account for soundscapes in urban planning, architecture, and urban studies generally.

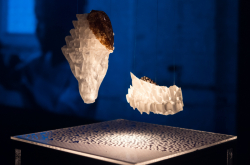

As we can’t simply turn off our hearing, we have to face all of the negative consequences of noise pollution that have a negative effect on our mind. At the same time, there is a wide variety of ways to make urban spaces more comfortable, such as, to plant more trees along streets, opting for rubber coverings instead of asphalt ones, and choosing where to locate sound sculptures, fountains, etc.

Schafer himself thought that in the future, sound designers would be as important as architects – because they would determine the well-being of city denizens.