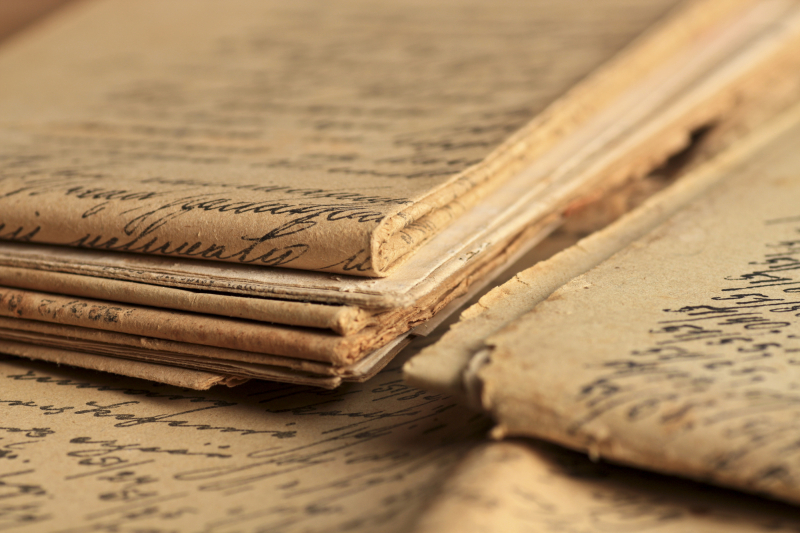

Among the earliest documents are census lists (revizskiye skazki). In this case, skazka (literally translates as a fairytale) has nothing to do with magic – it’s a document created during a revision (reviziya) for the purpose of taxation.

The first revision was held under Peter the Great’s rule in 1719. Its records included information on the head of a family (who remained the same even after his death) and relatives who lived with him – names, age, location of residence, and social category. Female and male parts of the family were listed in separate tables. Overall, 10 revisions were held in the Russian Empire; the last one in 1858-1859. To this day, many census lists are in great condition and help people trace their ancestors to as early as the late 17th century.

Other important documents were of religious nature. Before the civil registration system emerged, its workload basically fell on churches (or synagogues and mosques, depending on one’s confession). Christian parish registers (metricheskiye knigi) included entries on a person being born and baptized, along with the names of their parents, godparents and the priest, as well as records of marriage and death. Interestingly enough, parish registers had duplicates that were stored separately – in the church and at the eparchy, which proved to be beneficial for their preservation.

Moreover, as Orthodox Christianity used to be the official religion in Russia, every Christian over the age of 7 had to perform the Eucharist rite at least twice a year and regularly confess. All records on these rituals were included in confession registers (ispovednye vedomosti). Every church had a list of its parishioners with names and ages. Unfortunately, during the 20th century, such documents were largely destroyed.

A lot can be discovered using the records of the First General Census of the Population of the Russian Empire, held in 1897. It was the only nation-wide census performed in the country and it included thorough data on citizens. The idea was to destroy the lists themselves afterwards and only present generalized statistical data, but – thankfully for historians – not every institution followed this order and many documents are available for research to this day.

Among other documents that help learn about the people of the past are personal profiles created at their places of studies or work, as well as documents related to specific social categories. For example, you had to fill out an application to become a meshchanin (a Russian burgher of sorts), and such records can also be found in good condition.

If you would like to learn more, check out other stories about history on ITMO.NEWS, such as the one about birch bark manuscripts that can be found here.