What made you decide to become a journalist?

I was extremely well-read when I was a kid and I wrote great essays and articles for our school paper. So, when I had to choose a major, I thought that studying journalism made the most sense for me at that moment. Plus, I was eager to leave my comfort zone and overcome my shyness. It’s hard to tell whether I succeeded or not but even today I sometimes feel nervous when I have to interview other people.

Why did you choose science journalism?

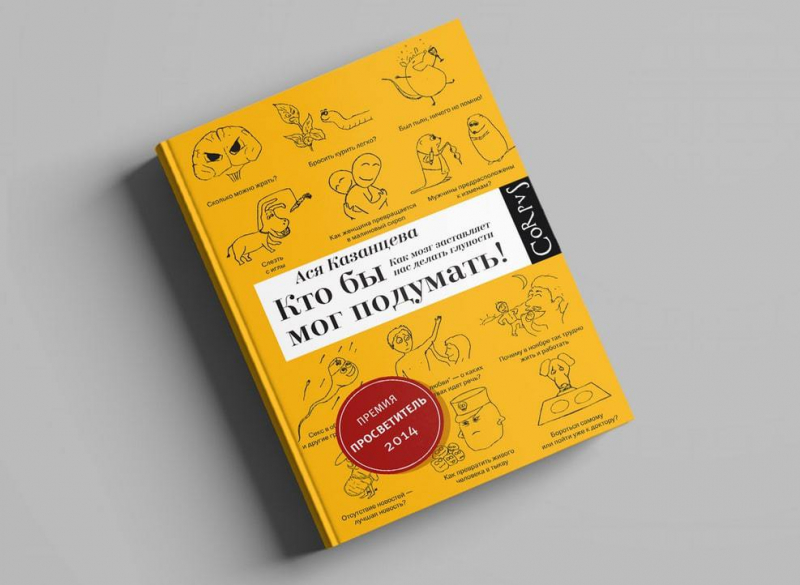

As a Bachelor’s student, I concentrated mainly on social issues and I thought that’s how it was going to be. Yet, once, one of my lectures told us about Asya Kazantseva’s (a Russian science journalist and a science popularizer - Ed.) book about how our brains make us do silly things. Though I only read it after I graduated, I was blown away by how well-written and interesting it was. I wasn’t that much into science but I then became excited to look into it from a journalist’s perspective. I began working consistently towards my goal. I enrolled in the school of science journalism by the Russian Reporter magazine and started to publish my articles around that time. Once I finished the school, I continued to work as a freelancer at the magazine. And I’m beyond grateful for the experience I got there.

The book by Asya Kazantseva. Credit: evolutionfund.ru

You mainly write about medicine and even have articles about oncology, why these topics exactly?

This was my next step. Science is a vast field that integrates a bunch of exciting topics. During my magazine days, I penned about space, zombies, and urban legends. Then, when I got pregnant and had my child, I became curious about child health and followed many experts’ blogs in this field. It was then I learned about the evidence-based approach in medicine. Knowing what to do in certain situations helped me a lot as a first-time mom. What’s more, I understood that medicine is fascinating and I wanted to write more about it. And oncology became one of my topics as I started the Master’s program.

Could you tell us more about it?

I was doing a paper on cancer prevention for Russian Reporter and reached out to Ilya Fomintsev, the head of the Cancer Prevention Foundation, to find speakers. It was he who advised me to study science communication at ITMO. I thought it was a great idea! I wanted to continue my studies yet I was afraid that I wouldn’t pass the entrance exams. I firmly believed that they looked for people with greater academic performances than what I had. However, I had lots of published articles under my belt and that helped me get in. I was over the moon because studying there meant new knowledge, new people, and new opportunities. Though, I had my doubts, too: after all, I was a mom and had to move and find a new job.

Ilya Fomintsev at ITMO. Photo by ITMO.NEWS

What are your most vivid memories about your university days?

I believe what I remember most is how understanding and caring people are at ITMO, whether you come on organizational or administrative matters or communicate with your lecturers or anyone else actually. My Master’s studies were not exactly like my Bachelor’s years. Here, you know that lecturers listen to you and are there to help you bring your ideas to life. We also had the chance to regularly meet experts from various fields who came to share their experiences. We could contact them, ask our questions, and even collaborate. Moreover, my journalistic experience came in handy when we had text-related disciplines.

Your article about stroke included not only information about the medical condition but also your father’s story. What were the reasons behind such a decision?

This was my first piece for Profilaktika Media (a website about evidence-based medicine and oncology – Ed.). I had an assignment to write about something from my personal experience. And I pitched the topic that vexed me heavily. The research I did helped me structure all the information yet I was scared to share my personal stories. However, once the article was out, I garnered a lot of support from my and my dad’s friends.

What’s your favorite article?

It’s hard to tell but I think it’s the stroke piece because this article is extremely personal and emotional. I always include this bit in my portfolio, as well as the article about child sexual abuse from the Russian Reporter. To put it together, I talked to specialists and a young woman who was sexually abused as a kid. She helped me gather stories for my article. Later, at one of our meetings, I learned that this piece was named the best in the edition. It was such an unexpected and nice surprise.

The homepage of the Profilaktika Media’s website. Credit: media.nenaprasno.ru

Do you have a hard time writing about such emotional topics?

It depends on how you see it. Take my articles about cancer, for instance. If I’m asked to speak about various risk factors without featuring anything personal, I detach myself and see this as an opportunity to learn something new that I can then practice – say, what I can do now to reduce my chances of getting cancer. Whereas when I talk about other people, I can't help but get touched by their stories. However, I don't do such pieces often.

When you were an editor at Profilaktika Media, did you find it hard to proofread texts as a non-medical specialist?

I did. But I had a community of doctors from the Higher School of Oncology who helped me believe more in myself. They were medical editors. Also, there are always information sources that are considered more or less reliable, such as the websites of the National Cancer Institute (US) and the National Health Service (UK) where you can find advice on how to prevent and treat a wide range of diseases.

Could you share your experience as a science communicator?

Science communicators do various tasks, depending on the organization they are in. I work at the Institute for Interdisciplinary Health Research (IIHR) where I produce scientific press releases, which, for instance, assess anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies levels among the city’s residents. I also communicate with journalists, set up interviews with researchers, write articles, and sometimes edit texts about our studies. At the moment, I’m also in charge of the university’s newsletters.

Science communicators and PR specialists have similar responsibilities. Yet while I can fully immerse myself in the topic and only write about all the aspects of the university’s life, PR specialists have other tasks, too.

How did you get into the European University at St. Petersburg?

I was offered a position by Anton Barchuk, the head of IIHR, who used to be my supervisor at ITMO. I enjoyed what the IIHR does in its fields: epidemiological and qualitative sociological research in medicine and health, as well as health economics. Back then, I thought it would be an interesting experience. Now, I mostly do science communication but from time to time, I write articles about medicine for the media, too.