Early life and education

Dmitri Mendeleev was born in the city of Tobolsk, in the far west of Russia’s Siberia, the youngest of a dozen or more children. Mendeleev wasn’t an A student at school, he was more of a last-minute type of person, which nevertheless didn’t stop him from finishing school.

There were many Decembrists in Tobolsk. Some of them even worked as public officials up to the civic governor. In what way were they different from the people Mendeleev would then get acquainted with in St. Petersburg, like Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov and others? The latter were the intellectuals who belonged to different social classes. They didn’t like the environment around them and wanted to change it, while the Decembrists were quite happy with their life in Tobolsk and did their best to further improve it: they established libraries, opened schools, organized concerts and so on. Mendeleev was somewhere in between these two groups, affected by both.

University years

Mendeleev wanted to become a doctor. The good thing was that to apply to the Medical Academy, one didn’t have to take any exams. The problem revealed itself later, at the anatomy theater, where young Mendeleev fainted during an autopsy. His mother advised him to apply to the Main Pedagogical Institute instead: one didn’t have to pay for education there, so it was a good opportunity to live off the state for a while.

Right after he was enrolled, his mother died of tuberculosis, a disease that had also taken one of his sisters. That was when Mendeleev realized that now it all depended on him and nobody else.

Though it was a difficult period for the young researcher, he finally moved on, started studying hard, and graduated from the Main Pedagogical Institute with honors, which served him well in his future career, as in the Imperial Russia excellent students received government fellowships for study trips abroad, mainly to Germany.

It wasn’t that simple though. You didn’t just get your diploma and head to the railway station, no. There was a queue, and Mendeleev had to wait for several years before he was finally given this opportunity. Meanwhile, he got his first teaching position in Crimea. He stayed there for only a couple of months and, after a short time at the lyceum of Odessa, defended his thesis, and went back to St. Petersburg to teach at the Imperial St. Petersburg University.

Trip to Germany

Financed by a government fellowship, in 1859 Mendeleev went to study abroad for two years at the University of Heidelberg. He didn’t really like the equipment at the university’s laboratory, so instead of working closely with the prominent chemists of the university, he set up a laboratory in his own apartment.

Vodka myth

Upon his return to St. Petersburg in 1861, he was offered a position of the professor of chemistry at the University of St. Petersburg. The only thing he had to do to achieve this was to defend his doctoral dissertation. That was the time when the state wanted to establish a monopoly over vodka and hard liquors. To do that, they needed an alcoholometric scale, and Mendeleev’s task was to come up with one.

The main difficulty was that it is impossible to obtain absolute alcohol by simple fractional distillation, because a mixture containing around 96% alcohol and 4% water becomes a constant boiling mixture. But Mendeleev was the first one to manage it. He created fully anhydrous, meaning absolute, alcohol. The scientist turned the 12 buckets of regular alcohol he was given into a glass of absolute, which was very handy if one wanted to dilute or concoct different substances.

Where did the 40-degree vodka standard come from? Not from Mendeleev: it was introduced by the government in the 1840s. The politicians noted that vodka has a peculiar tendency to water down as it was delivered to the consumers, and not from natural causes. So it was decreed that the beverage should have no less than 40% alcohol content, no less than 38% in retail. But that was only true for central Russia.

Mendeleev himself wasn’t that much of a fan of vodka as a drink; in fact, he hated it.

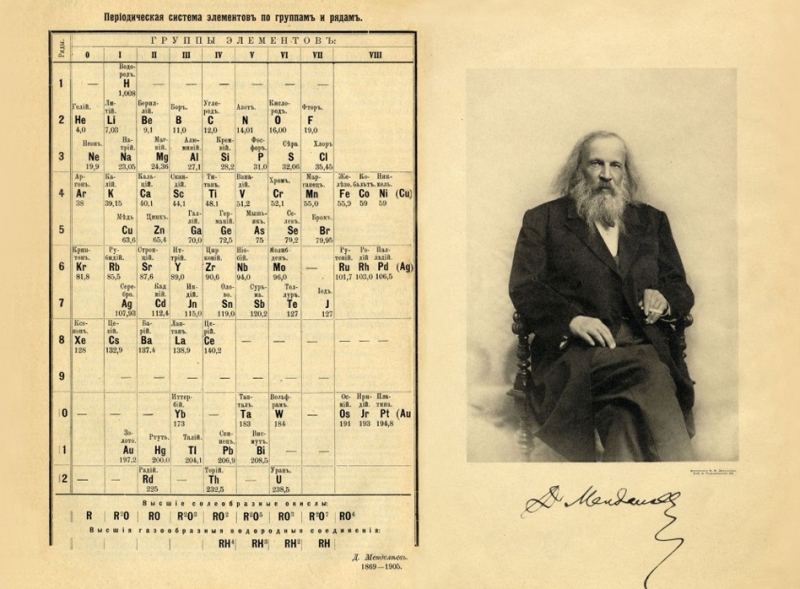

Periodic law of chemical elements

At one point in his career as a scientist, Mendeleev thought about contemporary textbooks on modern organic chemistry he could recommend to students and realized that there weren’t any. So he decided to write one himself.

It was when he was working on his Principles of Chemistry that Mendeleev discovered the periodic law of chemical elements. People say that it came to him while he was sleeping. This legend traces back to one of Mendeleev’s friends, but it appeared after the death of the chemist, in 1919, and not in 1869 when the law was discovered.

Mendeleev makes his discovery on February 17, March 1 n.s., writes an article, gives it to his other chemist friend Nikolay Menshutkin, and leaves for then-Tverskaya province to inspect local creameries. Menshutkin issues the first announcement on the newly-discovered law on March 6 n.s. The thing was, Mendeleev wasn’t that happy with his work and believed that this was just the beginning and the real work was yet to come.

The article proved to be a bit of flop, too. One scholar even said, “Dmitry Ivanovich, it’s time you did something useful for a change.”

What Mendeleev thought his real life-time task was

Any other person in his position would have dropped everything and wholly dedicated themselves to further researching the periodic law, but what we see in Mendeleev’s diary a year and nine months after his breakthrough are notes on pumps. What do they have to do with it, one would ask?

It is for us that Mendeleev is first and foremost the author of the periodic law, and we think this to be his main achievement. But it was just another step for him.

What was the problem Mendeleev cared the most about? World ether. Even the great minds of the Antiquity pondered over the notion that there is that subtle matter which penetrates the Universe. In the 19th century, they believed that it was the world ether that creates electricity, magnetism, gravity and chemical reactions, so that was a task and a half! If Mendeleev had cracked the world ether problem, he would have gotten the keys to all mysterium cosmographicum, cosmic mysteries.

His idea was simple: take a tube, completely suck it of air, and you’ll be left with world ether in all of its mystical glory. But for that you need pumps, barometers, and other equipment costing 40 grand a year. This was colossal money by his era’s standards. Where to take it from?

So he does his world ether study alongside prosaic experiments for the Imperial Russian Technical Society researching how gas behaves in gun barrels, all to keep himself afloat. This lasted for seven years, until it finally crept on his ‘investors’ that the whole ether thing was just their money going down the drain. Mendeleev proclaimed it limitation of scientists’ creative freedom and indignantly stopped his research in 1877. But privately he continued working on the idea, with his last work titled An Attempt Towards a Chemical Conception of the Ether.

Mendeleev in the throes of middle age crisis

After that whole ether business fell flat, Mendeleev developed a middle age crisis. First, he had to find a new research topic, as the last one failed famously. Second, he was sick of his one-hour-a-week university teaching. Third, he got this sudden urge to swap his wife for another. From all of his grandiose plans, this seemed the most feasible, so he started with that.

The solution to the wife question came in the form of Anna Popova, who had the misfortune of being his niece’s friend. He began to surreptitiously write to her from the next room, listen to her playing the piano, and even leg it all the way through Universitetskaya Embankment to the Imperial Academy of Arts where she was studying to do the talking. The society didn’t react in a positive way. He was a married man, father of two children, university professor, and running after a girl who wasn’t even 20 years old at that point.

The then-highest governing body of the Russian Church, the Most Holy Synod, did agree to divorce him from his first wife, but forbade him from remarrying ever again. But the resourceful scientist found a way out, bribing a priest and tying the knot with Ms. Popova. Soon a daughter Lyubov was born. The history remembered her for being the wife of Alexander Blok, the famous Russian fin-de-siecle poet.

Successful though his venture was, it all took a toll of Mendeleev, besieged by one misfortune after another. First he couldn’t get into the Academy of Sciences in spite of desperately wanting to, then he allowed himself a couple of anti-semitic statements whilst presenting a lecture, with one half of students clapping and another one rising in disgruntled uproar.

It all settled down in 1892, when Mendeleev established the Bureau of Weights and Measures, as well as Russia’s first weather office. His interest turned to economics. As a governmental expert in the field of economics, he proposed that Russia should develop the science-based industry. Otherwise, as he said, Russia could lose to the more pragmatic neighbors from the East.

Fatigued by constant squabbling with his fellow state bureaucrats and weakened by an especially bad cold, Mendeleev died aged 72 years old, leaving an enormous legacy behind.