There are still a number of missing spots in our knowledge of the Siege of Leningrad. What is your focus right now?

These days I study the economic history of the blockade in order to answer a question that I believe is fundamental: how did one million citizens of Leningrad manage to survive? Previous discourse in this area has mostly been focused on the differing estimates of the number of victims. At the Nuremberg trials, it was said that 632,000 people had died of starvation in Leningrad. This claim was supported by Dmitri Pavlov, the city’s wartime head of the food supply. But according to the well-substantiated estimate of historians Valentin Kovalchuk and Gennady Sobolev, that number was no less than 800,000 thousand.

While discussions went on about this topic, no one has drawn attention to the fact that, according to official data, out of the 2.5 million citizens, a million had survived. And that’s despite the inhuman conditions in which they lived. Our goal is to learn who survived and how, and whether there is a simple correlation between the categories of food stamps that people were assigned and their chances of survival. So far we’ve not been able to come to a firm conclusion.

These questions can only be answered if we look at a wider range of sources and try to learn about the food sources in Leningrad that have not been spoken about for one reason or another. For instance, the presence of certain food stocks among the population at the beginning of the war is partially related to a large number of seasonal workers in Leningrad at the time. This is just one of the questions, but it’s necessary if we are to understand how people survived under such paltry conditions. One of the theories I’m currently trying to confirm using sources, factory records, diaries, and NKVD archives, indeed concerns the subject of food reserves.

There is another equally important subject: we’ve never taken into account the fact that Leningrad was not a homogenous city. It had suburban areas, which contained vegetable gardens and farm plots. Back then, the traditional 0.14-acre dacha plots, which were moved much farther from the city after the war, were much closer to central Leningrad, and those who lived on the city’s outskirts had their own little farmsteads and, therefore, more chances of survival.

In addition, when we talk about food stamps, we often forget or just don’t know that there were more than three types of them. In fact, there were up to 20 types of food stamps for different categories of citizens. There were other important sources of food, such as army commissary stores, which are rarely ever mentioned, and so on. My goal is to tackle this complex set of social and economic topics, which includes studying nation-wide supply lines, and finding out whether everything possible was done to supply the city, or if something could have been done differently.

You’ve mentioned the need to analyze a variety of sources. In recent times, there has been a lot of talk about the pervasion of IT in all fields, including the humanities. These days we have the field of Digital Humanities, which uses digital methods to analyze social and cultural data. Do historians employ such methods in their work?

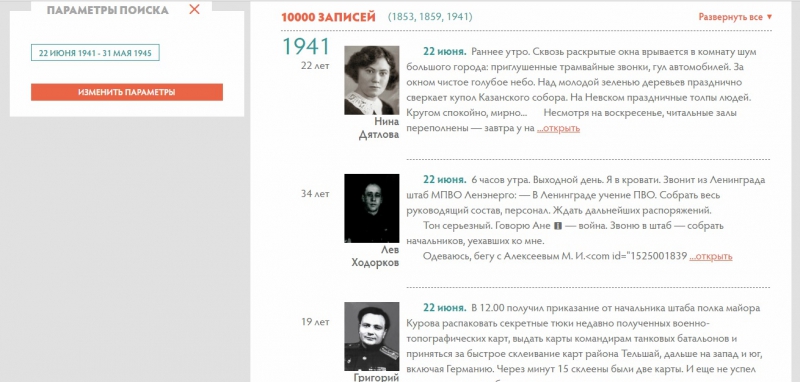

First, let’s figure out which kind of data we historians work with. There is, of course, statistical data. Do we need IT to process it? It’s not Big Data yet. The volume of information that historians work with, if we’re talking about the wartime period, isn’t that massive and can be handled using traditional methods. But I’m not saying that IT methods aren’t promising. I’ve spoken with an American colleague of mine, a sociologist, about analyzing the diaries written by citizens of wartime Leningrad to trace various terms that would signify changes in public opinion or the frequency at which certain issues were mentioned at different times.

Information technologies are incredibly important in content analysis. They are indeed promising, but much needs to be done first. Let’s say we have 1,000 diaries, all different in volume. And say we need to study the citizens’ attitudes towards various subjects: the Germans, the authorities, or various events. To do that, we must analyze the texts and find connections between the different bits of content. IT specialists along with the sociologists who’d need to decide what it is exactly that we should look for, and then analyze the results, could do some very important and fascinating work.

In that case, perhaps, we would transition from sharing individual anecdotal experiences to a more general level without losing the uniqueness of each human fate in the effort. I believe that there is space for collaboration here, but first, we need to digitize those texts, gain permission to use them, and talk to our colleagues in IT about our options in terms of software. And, first and foremost, we must decide what it is that we want to do.

Do your peers in other countries use such methods in their research?

Definitely not on the topic of the Siege of Leningrad. For instance, Alexis Peri, who has published a book about the Siege with Harvard University Press, also based her work on diaries, which demonstrate the atmosphere and the emotions of their time period better than anything else. After all, why do we study history, especially social history? To understand time through emotions. I doubt that technologies will be able to understand human emotion.

Then what is the benefit of IT for historians?

Technology can help us substantiate claims about changes in public sentiment, or to understand the factors that have affected these changes. For the citizens of Leningrad, we can assume that those were, first and foremost, the issues of the food supply. But there were other factors, too, and they were different for all categories of the population. Some began to starve by mid-October of 1941 and wrote about the city’s impending downfall, while others wrote about their reserves of potatoes in November and about being safe at least until the New Year.

But, I repeat, we mustn’t forget that we’re talking about something more nuanced. To work with large amounts of data and use IT, historians need to do their part, too: to identify the specific groups of people and set proper goals. Otherwise, if we simply aggregate data without understanding the core subjects, we’ll distort our knowledge instead of expanding it. If you’re trying to batter down a nail, you need a hammer, not a microscope. Tools must be picked according to one’s goals, and we can’t just involve IT in everything. We need to process some things on our own and use technology when we work with large data volumes.

Here is one example of such a task: during the Siege of Leningrad, more than 22,000 people were convicted for various economic crimes. There’s a large array of data which includes those people’s social backgrounds, the circumstances of their crimes, the times and locations where they occurred, the perpetrators’ marital and family status, etc. We can work with it, and, for instance, analyze the crime rates in different areas, city districts, at different times, among people of different social classes, and so on.

By the way, this is exactly what the Soviet law enforcement attempted to find out during the war. However, they did it using a slide rule and long multiplication and division. Today, we have different goals and different instruments. We’re trying to understand the geography of crime, which no one has studied before, and answer other questions nobody has asked before us.

A lot of attention has lately been directed towards projects made at the intersection of computer science and humanities not only for researchers but also for the wider audience. Take, for instance, the Prozhito project, which is, in essence, a platform for the publication of 20th-century private diaries. What’s your take on such projects?

Such projects are, indeed, actively developing. One other example is the project currently being made by the Presidential Library. They digitize historical documents and make them openly accessible, which gives us an opportunity to see them as they were, with markings and all. Because when we’re talking about documents that have once been handled by, for instance, Stalin, Molotov, or Mikoyan, it’s important to learn not only about the documents themselves but how these people reacted to them, which parts they chose to highlight, what mattered to them. Handwritten diaries are also very unique items. Wartime photographs and documentary footage are highly important. Projects of this kind allow us to become immersed in the subject and better imagine the events of that time.

Has there been any successful project of such nature on the topic of the Siege?

Indeed there have. But, for the most part, they are small initiatives supported by enthusiasts. Now, whether that is good or bad is a different question. But, so far, there have not been any serious scientific projects, save for the aforementioned Presidential Library project. Even then, they haven’t processed much material yet.

The need for such projects is enormous. Because so far there have been very few diaries published online that have also been verified to be genuine. Verification is extremely important, because I, too, could sit down right now and, knowing what I know, write a diary on the behalf of my grandfather. Historians should evaluate the authenticity of what they publish and provide internal and external reviews of their sources. There is a need for such work, and it is also a field where IT specialists could prove to be a lot of help.

Speaking of other methods of popularizing science: many museums, including those of natural history, have lately been implementing new, interactive forms of exhibition to attract their visitors and visualize their material. What are history museums doing in that regard?

Historians absolutely need to think about new technologies and find new ways of presenting information. In an audio form, for instance, so that diaries could not only be read but also heard. Or, if you go to any modern war museum in, say, France or the USA, you’ll see these headphones on the wall which you can use to listen to historical recordings or someone reading a contemporary account of some event. There is quite a lot of video content, too, although of course during the war there wasn’t always an opportunity for filming.

We’ve thought and still think about new formats. I’m not an expert on the museum trade, but, of course, visit museums quite often. And I can say that people of all ages are impressed by interactivity, by contact, and by the lack of edification.

But people need not only to see and imagine, but they also need to have things explained. Everyone is different, and some know more, some know less. In the case of teenagers, who haven’t acquired any in-depth knowledge yet, you need to hook them in first, and only then will they start reading books and such.

And how do you do that?

That’s a difficult question. And I don’t believe there is a universal answer. Some of us grow up in families that have certain traditions, where they can learn through photographs and their relatives’ stories. And this isn’t something you should learn through aggregated data. If someone tells you that 800,000 people died, it won’t make an impression. But if you were to learn that your grandfather or grand-grandfather died here, and see his death notice, the kind that informed people of their loved ones’ deaths; if you were to see that piece of paper, you might be able to imagine what it was like.

Stories should be interesting and emotional. When we’re talking about the overall story, like the loss of the old city, or the deaths of the intelligentsia, these stories are understandable to those who already possess the knowledge. Those who don’t would better learn through the stories of individuals. I think that’s the only way. It’s not easy to design a great exhibition. After all, it’s not just about the information, but how you channel it using accessible methods. And these methods must affect our emotions. But, most importantly, you have to evoke curiosity. And scientific interest comes after.

Nikita Lomagin is a Russian historian and expert on international relations, Russian foreign policy, and energy security, a doctor of historical science, and a professor at the Department of Political Science of the European University at St. Petersburg. Dr. Lomagin is one of the leading researchers of the history of the Siege of Leningrad.