You graduated from the Information Technologies and Programming Faculty. What made you choose that particular field?

In school, I was into computer science. One day in 1996, Vladimir Parfenov (head of the Faculty – Ed.) came to our school to talk about his department. It seemed an appealing prospect, so I took the exams and never even considered a different option.

I have good memories of my time at the university – I think it was one of the best choices one could make back then in terms of education. Later experience demonstrated that we were given exceptional mathematical and computer knowledge, but there was still much to learn about physics.

How did your interests end up shifting towards physics?

By the second year, I was just no longer interested in pure programming. Thanks to Sergei Kozlov (head of the Faculty of Photonics and Optical Information – Ed.), I joined a project on physical processes modeling at the Vavilov State Optical Institute. That was a lot more interesting than simply programming.

What sort of project was it?

We modeled nonlinear optics, which called for a simple way to solve nonlinear equations. My Bachelor’s and Master’s theses both dealt with different solutions to that issue. I also published several works, some in international journals. Back in the early noughties, it was difficult to communicate with those.

Life in the US

You moved to the US while you were a PhD student at ITMO University. How did that happen?

A couple years before I moved, I met an American professor at a conference in Veliky Novgorod. The professor was visiting friends in St. Petersburg, so we took the same train and spoke on the way. At the end, he gave me his contact info and told me to get in touch with him. He worked in Montana – not the biggest place for research, but nevertheless he was among the best in his field. He ended up inviting me to Montana State University.

How did your move go?

It took me almost a year. I had to provide my diplomas, translations of all my documents, TOEFL results, and to pass GRE tests: General and Physics. GRE General is a complete shock to a regular person. It had two parts: mathematics and language, the latter was especially vicious. You’re given twenty words that you’ve never heard before – and you have to pick two synonyms or antonyms from among them. This is to see how well you’d be able to help out professors during lectures.

And what about the journey itself?

I didn’t even know where I was going. I spent the first couple of nights at the house of the professor who invited me; then, I moved to a dorm. The dorm for PhD students was nine stories tall, probably the tallest building in town. It had a marvelous view of the mountains.

Everything was different, though it was relatively easy to adapt. At first, I went to stores with my superiors and they’d tell me what’s edible and what isn’t. Almost everyone at my lab spoke Russian.

How different was the educational process from what you’d already experienced as a PhD student in Russia?

First off, in the US you have a set of classes that you’ve got to take and some electives that you choose. Because of that, the students in each class are different. Each class follows a textbook, which was a novelty to me. Back in Russia, we didn’t use any; here, you had these clear-cut texts and no need to write down notes. In fact, you could even look up the contents of a lecture in advance.

As for scholarships, that depended on the department. Our physics department in Montana provided all students with a stipend of about $1,500 per month and a partial medical insurance. It wasn’t much, but enough to live properly.

And in terms of research?

The biggest difference was here: back then, in Russia, you’d do everything at home and meet your thesis supervisor a couple times a week. In the US, it was different. The lab was inside the academic building and each student had a key. You could come in to work at any time of day or year. We even worked on December 31 once. Each lab is an independent team and the department is just a building where everyone works on similar topics; but there isn’t a single director who’s in charge of everyone. Every lab is in charge of its own funding.

What sort of research did your lab do?

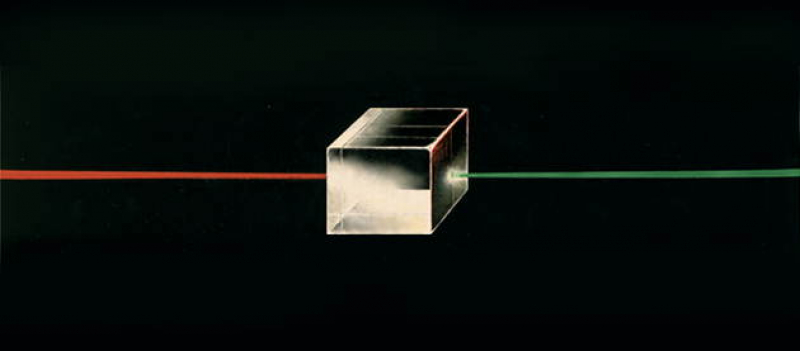

I worked on the measurement of two-photon absorption in organic substances. Basically, we grabbed huge lasers and used them on solutions of various molecules and proteins. If you replace a laser with regular light in the same wavelength – we used the red and infrared ranges – it passes through without absorption and nothing happens.

If you take a femtosecond laser and focus it on the substance, the laser radiation is absorbed at the focal point and the substance begins to glow. This is useful in many applications. Back then, in the mid-00’s, 3D optical memory was a subject of interest as it offered the opportunity to store a terabyte of data in a cubic centimeter of matter. One concept straight out of fiction was the optical blocking of laser capacities – for example, in glasses for fighter pilots that would immediately darken when hit with a laser so that the pilot doesn’t go blind.

We also talked about cancer treatment and the prospect of pointed tumor removal that would leave the rest of the tissue unharmed. Two other fields that eventually developed the most are optical three-dimensional nanotechnologies, which is, for instance, the focus of Pavel Belov’s team at ITMO University, and three-dimensional microscopy, which is the ability to monitor the changes in cells and entire organisms in real time.

Montana to Georgia

When and how did you move to Georgia?

When you’re getting a PhD, you eventually face the question of what you’re going to do once you graduate. You can be a postdoc, but where? Every winter, the Photonics West conference takes place in the US. I went there before my defense with two reports. Before me, three or four other speakers showed excerpts from an article I worked on and compared their research to ours.

Naturally, when I came up to deliver my reports, people showed interest. I spent almost an hour after my talk in conversation with a professor. I said that I’ll be graduating in the spring and he offered me a position at Georgia Tech.

Was your work there different from what you did before?

In Georgia, I continued on what I began back in Montana: I improved on our system and took part in different projects, including ones that dealt with quantum dots.

I spent almost two years there – a normal amount of time for a postdoc. It was all the opposite of Montana. Instead of a small town, I was in the massive city of Atlanta. Instead of a 15-minute walk to work, I had a 90-minute commute by car or train. But there was one huge upside: five Russian stores nearby which sold a variety of tasty things quite cheap. You don’t appreciate that in Russia, but after Montana it was a pleasant discovery.

And what came next for you?

I found work at the Los Alamos National Lab. In the US, there are three types of places that do research: universities, private companies, and national laboratories. The latter are massive institutions with a lot of funding, and, since they’re not educational, the staff have more time for research. And you don’t need to apply for grants much, since the funding is already there. One research group at Los Alamos has three buildings to itself: an office and two hangars where the laboratories are.

The employees all live in a small town that only exists because of the laboratory. It’s a unique place – the country’s most well-educated city, where a third of the population has a PhD and 60% have at least one diploma. It’s one of the wealthiest counties in the US, too with some of the best schools, the best-funded police force, and one of the highest average incomes. The number of millionaires per capita is also among the highest, and this is all thanks to the laboratory. Because of this, the city is often ranked among the nation’s top lists of small towns.

What did you do there?

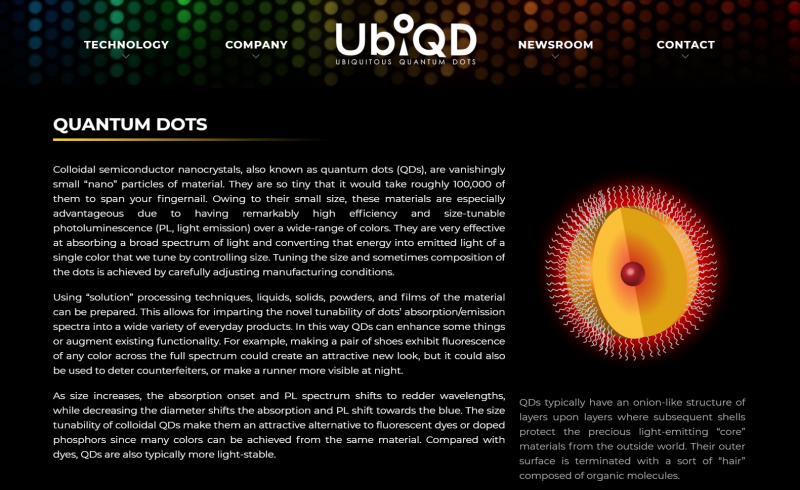

I studied optical effects in various types of quantum dots. We wanted to describe the causes of photoluminescence in CIS quantum dots and to understand some of the inconsistencies between perovskite quantum dots and other, more conventional quantum dots. We even developed quantum dot-based film that would function as a scintillator and detect neutrons. I did this for four years.

What made you move to UbiQD?

They have this thing at the national lab: they believe that postdocs must only work at one place for two years, maybe four, but not more.

Why? Because here, they believe that a person only learns for four or five years. Then, they start to “gather moss” and stop learning. The idea is that to keep learning things, you need to keep moving. When my four years were up, I wanted to stay in Los Alamos, but couldn’t stay at the lab.

A colleague of mine had just finished a project on quantum dot synthesis and was working on ways to produce them cheaply and in large numbers. He decided to capitalize on his work and start a company. First, I was taken on as a consultant for a couple of months, but ended up staying as a full-time employee.

How difficult is it for an experimental physicist to start their business in the US?

Right now it’s very difficult. It was a bit simpler back in 2014, and it would have been even easier a few years prior. Today, most investments go towards computer technologies. Companies that produced solar cells began to go bankrupt in 2014-2015, when all production moved to China. Nevertheless, my friend secured investments from business angels, received some grants, and began perfecting his technology.

What is your role at the company these days?

Essentially, we’re optimizing the product. It’s research work and we need to understand what happens to the material and what we can improve and how.

To Russia

In all that time, have you been keeping in touch with your home country?

Since I had a student visa when I moved, I couldn’t go anywhere. I got a work visa when I moved to Georgia. I finally visited Russia in 2014 – and it was a completely different country.

How interested would American scientists be in collaborating with Russian institutions?

When I worked in Montana, we collaborated with specialists from Moscow. They developed different fluorescent proteins, we measured them, and some good papers came out of that. I think that there’s always interest, but there are certain limitations. For instance, most grants in America specify that the funds must be spent on US territory and aren’t designed for collaboration with other nations.

Considering your experience – what would you tell today’s students who are interested in doing research?

If you really want to do science and achieve something, you must understand that the competition is high. You need to join renowned research groups from the very start. Publish your work in good journals and make a name for yourself. Then, it’s best to get a PhD at a top university and find a position as a postdoc. Change your area of study every time, study new things. If you want to be a professor, you’ll be expected not to simply repeat what you’ve done for your thesis. You’ll need to put forth new things. And remember: if Google Scholar doesn’t know you, nobody in science does.